Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Plato and Democracy

Could Plato’s Republic Work In China?

Keith Hui compares the Chinese state to Plato’s republic.

Plato disliked democracy. In The Republic, as a substitute for elections, he proposed a rotational succession model for his ideal government: “those who have come through all our practical and intellectual tests with distinction must be brought to their final trial… and when their turn comes they will, in rotation… do their duty as Rulers… when they have brought up successors like themselves to take their place as Guardians, they will depart” (540a-b, translated by Desmond Lee). The elites are trained with mathematics for ten years, dialectic (philosophy) for five years, and “military or other office” apprenticeship for fifteen years (524d-540a), and finally selected as rulers after passing a series of tests. This can be regarded as a form of meritocracy. They govern the state and bring up their successors, then hand over the authority to the next team, and retire.

Deng Xiaoping at the White House

In China, Deng Xiaoping also disliked democracy, but he didn’t like the lifelong rule of Chairman Mao Zedong either. After a number of chaotic years in the 1980s, Deng appointed Jiang Zemin as the President and Zhu Rongji as the Premier. Unprecedentedly, he also instituted a rule that no one can serve any leading positions for more than two terms of five years each. He also instructed senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cadres to establish a nationwide system of party schools, as well as other academies for preparing young members, and upgrade the Central Party School. In 2003, despite some minor irregularities, Jiang and Zhu followed the late Deng’s ruling, and handed over their own positions to the Hu-Wen team. Having served for ten years, Hu and Wen passed on the authority to Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang in a more institutionalised manner in 2012/13. So the Peoples’ Republic of China shares three major leadership features with Plato’s republic, namely, statecraft training, rotational leadership, and end-of-tenure retirement.

Justice, Plato argues, means that each citizen should be “just minding his own business” (433b-434c). Unlike Jesus, who conceptually equalizes all humans by suggesting that we can all be children of God, Plato tends to focus on the differentiation of people in terms of their characters and passion for wisdom, and he does not see equality as either sensible or desirable. He believes that “no two of us are born exactly alike. We have different natural aptitudes, which fit us for different jobs” (370a-b). So it is just that each person should do what is apt for them: i.e. his or her ‘own business’. Then Plato argues for a dichotomy between a market economy, where the general public are free to work, trade, own private property and raise families, and an authoritarian government controlled by a caste of Guardians without private property or family (416d-e, 457d). The Guardians, who love and possess knowledge, serve the state as decision-makers and soldiers (the ‘Rulers’ and ‘Auxiliaries’), while the ordinary citizens, who instead of knowledge have only ‘opinions’, are limited to various types of social and economic activities. To save his Guardians from corruption, Plato prescribes a communal style of living for the governing caste. However, perhaps Plato’s scheme is not workable in the real world. David G. Ritchie called it a “typical representative of fantastic and unpractical dreaming – the outcome perhaps of ‘the genial cups of an Academic night-sitting’” (Collected Works of D.G. Ritchie, 1902).

The Chinese people, who have a two thousand year tradition of civil service examinations, share Plato’s concept of justice to a significant extent: they also think that only those who excel at scholarly studies should oversee public administration, up to the rank of chief minister. Quite different from Plato’s closed society, though, in China the gate for entering the government has been open to the public since ancient times. Thus there is a deep-rooted national aspiration to sociopolitical mobility by taking part in a series of civil service examinations, through which any talented commoner can become a well respected intellectual-turned-bureaucrat. In modern China too, very naturally, both the civil service and CCP membership are open to citizens. This is the first major variation from Plato’s model. Another variation is that all citizens, including CCP members, are allowed to have a family, and (after the end of the 1967-77 Cultural Revolution) to own private property.

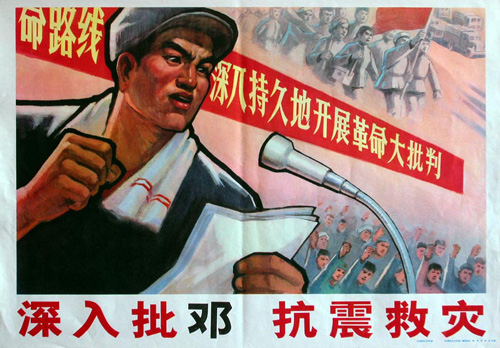

A propaganda poster denouncing Deng Xiaoping c.1970. (Many thanks to Maopost.com poster collectors’ site.)

Well known for his pragmatism (Deng’s Cat Theory: black cat or white cat, who cares? The one that can catch rats is a good cat), Deng Xiaoping reshaped China in two respects. Economically, capitalism in the guise of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” was launched in the early 1980s to provide ordinary people the freedom to engage in a wide range of commercial and financial activities. Politically, efforts were made to institutionalize a rotational succession system. After starving for stability and prosperity for more than a century, the Chinese people do not see their leaders as philosophers, but as ‘helmsmen’ for economic growth. China has thus pragmatically turned Plato’s rotational Philosopher King ideal into a rotational Helmsman Ruler System. This non-democratic Helmsman Ruler System fulfills Plato’s conception of justice as each person “minding his own business” by specifying that only those purposively trained for statecraft are authorized to mind such businesses as public administration and diplomacy, whereas the ordinary citizens should remain politically unconcerned in order to be freely mindful of their commercial or industrial stakes. Any citizen interested in politics should join the CCP or civil service through the prescribed channels, and climb the hierarchy along party lines. The political freedoms of those outside the Party are restricted to the areas demarked by the socialist constitution.

The Helmsman Ruler System can be viewed as a large-scale philosophical and political experiment with Platonic non-democratic governance. It appears to be superior to monarchy, aristocracy and military dictatorship. Yet although batches of competent leaders coming to power in rotation to serve the national interest may sound very appealing, there is a weakness. The success of this experiment depends on whether the members of the governing party are able to exercise a sufficiently high level of self-discipline to prevent moral deterioration, in the absence of external checks and balances (such as an independent judiciary or periodic multi-party elections). In The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1790), Adam Smith suggests that according to Plato, “virtue consists in propriety of conduct.” Justice in Plato’s sense can only be achieved when both the governing class and the general public practise this virtue. If and only if this is so, this meritocratic Chinese regime may be sustained and grow strong.

© Keith K.C. Hui 2014

Keith Hui is a Chinese University of Hong Kong graduate major in Government and Public Administration. His new book Helmsman Ruler compares China’s rotational power practice with Plato’s prototype and other models of power.