Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

War & Peace

Interpersonal Peace & Refusing Abuse

Jessica Park shares some personal lessons in peace.

I recently ran into an acquaintance I hadn’t seen in several years, and his first question was, “How are you?” That was easy to answer; I was out with my kids and a few friends at a local festival. Without hesitation I said, “I’m great!” He followed up with a second question, “What have you been up to the last couple of years?”

That one was less easy. The first response that flashed through my mind was a bit sardonic: “You know, the usual… I married an abusive alcoholic, which turned out to be a bad idea… so, I’m divorced again.” But that internal response was tempered by the immediate follow-up, “Now I feel stronger and more joyful than ever.” Of course, I didn’t say any of that out loud. It’s more information than I want to share in a casual conversation. Nevertheless, the question and my internal response stayed with me, and have helped me to think about what peace and justice mean at the interpersonal level, that is, between individuals. While my experience is unique in many ways, the challenge of confronting interpersonal violence and creating peace is one that will resonate with many people. Through these personal struggles, we find the resources within ourselves to confront violence and injustice wherever we see it.

Naming Injustice

Part of confronting violence and injustice successfully is having a vision of peace – a vision of how things could be better.

Although I had my share of hardships to earn my PhD, tenure, and eventually promotion to full professor, I am not one to give up easily, and I enjoy proving naysayers wrong when they underestimate me. I am also known for being talkative and outgoing, willing to take on intellectual and physical challenges, and a generally optimistic person. My image of who I am certainly didn’t include being married to an abusive alcoholic; but it was only by recognizing what was happening to me that I was able to actively start creating peace again.

My ex-husband wouldn’t recognize himself in the description ‘abusive alcoholic’. His self-description is that he’s a ‘problem drinker’, since he can’t stop drinking once he starts; but that he’s not an alcoholic, since he doesn’t drink every day. As far as being abusive, he reasoned that other women had it worse than I did. For him, verbal abuse really isn’t ‘so bad’ compared to physical abuse. As for the bruises on my arm and leg, my twisted ankle, and the destroyed furniture, he reasoned that none of this would have happened if I hadn’t been trying to leave him. He also believed that because he tried to stop drinking, tried to stop threatening me, and tried to stop calling me ugly, hurtful names, that the problem was my perception and not his behavior.

His final defense of his actions happened when I walked out the door for the last time. He asked me, “Why would you leave me now? I wasn’t as bad as the last time you left.” But I had learned two major things that are important for stopping interpersonal violence, that would in turn help to create personal peace. First, I stopped letting my abuser define what was happening; second, I stopped taking the blame for his violence. Although I would have liked my ex to recognize that he is an abusive alcoholic, naming injustice and standing up against it does not require agreement or cooperation from the oppressor. In fact, the only possibility for him to recognize his abuse was for me to name it and to refuse to participate in his euphemistic justification of it.

One of the key components to creating peace is to recognize when injustice is taking place. Another is to examine the ways in which we allow it to take place. Such examination may at first glance seem to be an example of blaming the victim; but what it actually does is to allow those who are oppressed to recognize their agency and to use it. Consider the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-6, which started when Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger who had boarded after her. Parks and the black community recognized the injustice, and refused to participate in it by boycotting the Montgomery buses.

In my case, I knew that the insults, the threats, the intimidation, were not loving, and not acceptable ways to be treated. Yet as long as I stayed and allowed the pattern to repeat, he got the message that his behavior was acceptable.

The first time we had an argument, he blamed me, and I believed that it was my fault. I believed that since his tirades, his anger, his threats were directed at me, I was responsible for his behavior. And since I was responsible (as I then believed), I believed I could find the right combination of action or inaction to spur change in him. I stopped striking up conversations with strangers; stopped seeing most of my friends; and stopped going to anything in the evenings or on weekends without him. All of this happened gradually, so even when I was finally able to recognize his abuse for what it was, I hid the truth and tried to manage the behavior. As an intelligent woman who had fought hard for respect, it was humiliating to admit to myself and others that I had married an abusive alcoholic. But I needed to come to see what I was allowing myself to believe, and so what I was allowing to happen.

Humility

This leads me to another important component of interpersonal peace: humility. I had to become humble in order to admit that I can control only what I do and my reactions. Knowing that, and living it out, creates ways for peace to flourish. Humility, in this sense, is not a false modesty that fails to recognize my particular talents and abilities. Instead, humility recognizes that I can act, grow, and respond; but that I also have to recognize my limits, and give space to others. So although philosophy frequently characterizes the pursuit of truth as a lonely or at least individual project (Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the Cartesian cogito are paradigmatic of this perspective), I have found that for me truth and insight happen through relationships in which I’m challenged and supported. Those are the relationships that have pushed me to see what I would otherwise ignore or resist. In the midst of the abusive relationship, certain people around me helped me to recognize both the toll that the abuse was taking on me, and the power that I had to stop it and create peace instead.

For people who have suffered from violence in many contexts and in many ways, a common coping mechanism is to try to find strategies to escape the notice of the oppressor: to stay at the margins of society; to move quietly to the back of the bus; to avoid eye contact and conversation. For people who had known me a long time, their concern centered around my weight, which kept dropping and dropping. I’ve always been small, so there was nothing healthy about my weight loss. Loving people around me recognized it for what it was: an attempt to take up as little room as possible and escape notice. But trying to avoid notice by shrinking only gave the injustice and violence room to expand. To make the violence stop I had to stop cooperating with it.

My description so far probably makes it seem as though I were walking through life so scared that I jumped at every shadow and avoided interactions with everyone around me. Rather, I had fairly successfully separated my marriage from the rest of my life. I was deeply involved in my career, and loved the time that I spent with my colleagues and students. I also spent as much time as possible with my kids and their activities. The division between my life with my husband and my life apart from him is what finally gave me the courage to act definitively toward peace. As I was walking across campus one day, I saw a colleague, and stopped to talk to him. I smiled as I walked toward him, and he said, “You’re the happiest person I know. You’re always smiling!” That same day I was in the car with my husband. He snapped at me, “You’re the most unhappy, depressed person I have ever met!” The contrast between those two perspectives stayed with me. I soon realized that I had a choice to cultivate happiness or unhappiness, peace or violence.

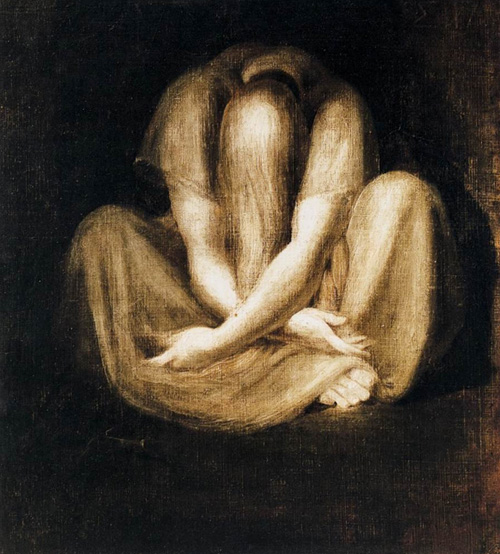

Silence by Henry Fuseli (1801)

Peace

Every step of my progress toward peace was both about me as an individual with particular choices to make, and about my relationships with others. When I recognized the violence and made a choice to stop participating in it, I achieved my goal by drawing on my strengths: my intelligence, my strength of will, my exuberance, my optimism. But my ability to draw on those strengths comes from my relationships with others. My family and closest friends recognized my struggle and continuously reminded me of my strengths. My colleagues and students continued to trust me with the challenging research, teaching, and service work of a university community. All of these allowed me to acknowledge that I cannot choose sobriety and kindness for someone else. When I embraced that limit, I became free to use my strengths to construct new paths.

Interpersonal peace is very much like social peace: it is less about freedom from constraint, and more about freedom for cultivation of potential. I’m describing peace as ‘cultivation’ because I want to emphasize the deliberate growth that’s encouraged with true interpersonal peace. A well-cultivated garden tends toward diversity and complexity, and it is resilient and ever-changing. The cultivation of peace requires all this as well. Our relationships should become increasingly diverse and complex so that we have networks of people who support us and are supported by us. We should also know that peace will be continually reevaluated and redefined rather than static and stagnant. Finally, peace does not preclude struggle, conflict, sorrow, or pain; but it gives us the emotional, physical, and relational resources to overcome and flourish both in spite of and because of the difficulties.

Interpersonal peace requires a balance between care for myself and care for others; a balance between intellectual pursuits and physical pursuits; and a balance between local care and global care. At this moment in time, my primary focus is on supporting my kids as they find their paths in the world. Even as I support them, I know that they need a model for how to value themselves as individuals; that I need to be shaping my own path for the future when they’re adults; and that I want to help shape a peaceful world for them.

© Jessica Park 2014

The author is an American philosopher. It has been necessary to alter her name for legal reasons.