Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Street Philosopher

Secure in Sindh

Seán Moran gets to grips with guards.

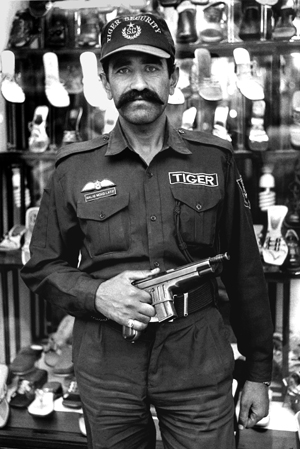

The armed security guard in my photo is on duty in Karachi, in the Sindh province of Pakistan. He’s protecting a ladies’ shoe-shop against potential thieves: sandal stealers and kittenheel kleptomaniacs. A more dangerous threat would be dacoits – local bandits – robbing the shop of the day’s takings. But our man has been issued with three bullets (he showed me) and is ready to take on any three villains. (Despite the similar macho name, Tiger Security Services of Karachi are different from Tiger Bouncers of Karachi – who don’t actually bounce tigers, but offer to protect celebrities.)

Security workers of all stripes are a common sight on the streets in this region of the world. Neighbouring India has over seven million private security guards. In industrialised countries, private security personnel are also becoming more numerous than ‘proper’ policemen and women. For instance, in Britain there are now more than twice as many private security operatives as there are police officers (Benjamin Koeppen, PhD thesis, 2019). Similarly, in the United States there are over a million private security guards, comfortably outnumbering the police.

Security, in its broad sense, is a public good. According to philosophers in the tradition of Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), the first duty of a nation state is to protect its citizens from harm, providing defence forces and police services to tackle external and internal threats. This gives military and law enforcement personnel a certain prestige, as supposed guardians of our national and personal security. In a democracy, they theoretically work for us.

Photo © Seán Moran 2019

But private security does not generally conduce to the public good. A shop’s security is there first and foremost to protect the stock, staff and premises, rather than to safeguard the general public. And security guards are well aware of this role. A study by Hansen Löfstrand et al. (‘Doing ‘dirty work’: Stigma and esteem in the private security industry’, 2015) reports on “the commonly used phrase ‘I’ve been bought’”. This work also shows that the general public looks down on retail security guards as being ‘tainted and disreputable’. They have to “manage stigmatised people, and need to behave in a servile manner to both employers and customers.” Combine this with their long working hours in sometimes hostile environments – performing mainly unskilled, boring duties for low pay – and it’s no surprise that staff turnover is high. It seems that security is an insecure occupation.

In spite of this, the sector is growing. Private security guards patrol buildings, city streets and shopping malls (which themselves have an ambiguous public-yet-private status). They operate prisons and refugee centres, and even undertake secret operations in conflict zones. This looks like a major mission drift from their former role of ‘night watchmen’; but in reality, private security has been involved in warfare and policing for hundreds of years. For example, the privately-owned British East India Company ruled in India from 1757 for just over a century, governing directly with its own army and police, before the British Crown took over (with Queen Victoria eventually becoming Empress of India).

Public Insecurity

Retail security has become more and more pervasive in recent times. We may wonder why shops now need to be so heavily guarded. Some of this is due to complex social and economic changes, but it is also likely that retailers themselves have partly caused the state of affairs. Consider a traditional town centre jeweller’s shop. The rings and watches are behind glass, so we must ask a shop assistant to unlock a display cabinet in order to handle the products, and we can’t escape until staff discreetly press a door-release button. There’s maybe no need for a security guard here.

Contrast this with a department store such as TK Maxx (called TJ Maxx in the US). Here we can freely handle watches and jewellery on open display. The very act of absent-mindedly picking up one of these may create a desire for it. This could lead to an impulse buy, or an opportunistic theft. The shop seems almost to invite crime by displaying the slogans ‘Finders Keepers’ and even “Shoes for a steal… grab them before somebody else does”. Now a security guard is needed, and CCTV cameras, plus electronic tags on products, alert the guard to shoplifting activity.

I once found an electronic tag in a café, together with hangers and labels, left behind by some shoplifters who had been taking a tea break. I put the tag in my jacket pocket to return it to the shop the next time I visited. Weeks later, I’d forgotten about the device when I wore the same jacket again and went to the mall. What drama! Alarms sounded every time I entered, exited, or passed each shop in the mall, and security guards started following me around. I eventually handed the tag in to the shop.

I’m not singling out TK Maxx for criticism. Many retailers do what they can to create a desire that they will satisfy for a price. But the strategy of tempting browsing shoppers by putting attractive products on open display makes illegitimate as well as legitimate acquisition easy. The process is seductive, frictionless, and perhaps not totally voluntary. (It’s not involuntary either, or shoplifters would have a useful ‘get out of jail’ card, to deny their culpability). To reduce illegitimate acquisition of the shop’s bounty, the security guard steps in.

Here in Ireland, we don’t trust even our regular police with guns; but in some countries civilian security guards are routinely armed. If you have lunch at McDonald’s in Madrid you’ll be watched by a uniformed private guard equipped with handcuffs and a pistol. According to a recent United Nations report, 24% of private security guards in Spain are armed: with higher rates in Bulgaria (40%), the Dominican Republic (80%), and Colombia (85%).

This is not a welcome development. Philip Zimbardo’s ‘Stanford Prison Experiment’ of 1971 showed that even decent, intelligent people can become sadists when put in uniform and granted power over others. If security guards are given weapons and a sense of authority, some of them will behave badly. For example, in 2007, private guards from the American business Blackwater Security Consulting “shot thirty-one innocent Iraqis in Nisur Square, Baghdad… Fourteen of the Iraqis, including women and children, died” (NBC News, 2018).

The Paradox of Protection

One fascinating philosophical analysis of security involves the notions of ‘immunity’ and ‘autoimmunity’. Paradoxically, when there is too much emphasis on achieving immunity from threats to the self, the defences activated can damage the thing they are supposed to protect. Here the French philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) uses the metaphor of autoimmune disease, in which the immune system attacks the host organism’s own tissues. Another French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007), points out that the nastiest pathogens emerge in the most sterile places: the highly resistant hospital superbug Clostridium difficile, for instance. Analogously, the presence of large numbers of armed security guards (especially together with gun-toting private citizens) raises the chances of injury to the very people who are trying so hard to achieve immunity from attack. This is an arms race that doesn’t end well. Derrida thus recommends an ethics of hospitality instead of an ethics of security. I’m with Derrida on this. I’ve been offered armed security in some of the places I visit, but prefer to trust the hospitality of local people.

An earlier understanding of immunity as protecting the ‘self’ from the ‘non-self’ is now dismissed as a naïve view, as there is no clear-cut demarcation between self and non-self, either socially or biologically. For instance, more than half of the cells in our bodies are non-human, but are essential to our health. Certain bacteria in our guts are vital to digestion, help to regulate appetite, and are involved in our immunity, but are organisms with completely different DNA from our own bodies. If these micro-organisms are removed by powerful antibiotics – analogous to over-zealous security – the niches that were occupied by these harmless or useful microbes become available for dangerous pathogens to occupy.

The German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk coined the term ‘ Immunitätsdämmerung’ to describe the crisis in the immunity system/modern civil security. The word is a nod to Wagner’s opera cycle Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) or perhaps Nietzsche’s book Götzen-Dämmerung (Twilight of the Idols); but it is the idol of traditional immunity whose twilight we are witnessing. In new models of immunity and security, the principle of toleration is paramount. The human immune system has to tolerate, not attack, its host: it must also tolerate those non-human elements needed for healthy functioning. Rigid self/other activity – particularly when it involves a Manichean (good/bad) element – is unhelpful. We are radically interdependent, both biologically and socially, so should not attempt to cut ourselves off from our surroundings using either antibiotics or guns.

Let’s return to private security in Sindh province with a historical example. General Sir Charles Napier commanded the East India Company’s private Bombay Army in Sindh. In 1842, acting against orders, he defeated the Muslim rulers and conquered the province. (He reportedly then sent a punning single-word message back to London: ‘Peccavi’ – Latin for ‘I have sinned’ = ‘I have Sindh’. We could credit Napier’s erudition and wit to his education in Ireland; but it turns out that the story is Victorian fake news. The pun was not his, but appeared in the humorous magazine Punch rather than in the General’s official dispatches.) Napier later regretted the conquering of India by private enterprise: “The object”, he wrote, “was to enrich a parcel of shopkeepers – the ‘shopocracy’ of England.”

In common with their light-fingered visitors, shopkeepers’ intentions have never been entirely benign. But we can still engage beneficially with them, as with the other ‘non-self’ organisms in our environments, internal and external. And we can gently subvert their security measures by treating guards as fellow human beings rather than anonymous uniformed cogs in the security apparatus. They are used to being treated with disdain by customers, shoplifters, and shopkeepers. Whether they are armed or not, a kind word from us – and perhaps a handshake – shows human solidarity and affirms their personhood. It also subtly challenges the legitimacy of private actors policing the public realm.

© Dr Seán Moran 2019

Seán Moran teaches postgraduate students in Ireland (still a member of the EU) & is a professor of philosophy at a university in the Punjab.