Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Jonathan Edwards on Spiders

John Irish reveals the surprisingly Enlightened views of a hellfire preacher.

On July 8, 1741, the parishioners at the Congregational Church in Enfield, Connecticut, were in for a real treat. They were going to hear a sermon from a visiting minister, one of the leaders of the First Great Awakening, a religious movement which had begun in 1738 and was now sweeping across the American colonies. That address would go on to become the most famous sermon associated with this movement, and the most famous work from that minister, if not the most famous sermon in American history. The minister was Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), one of the leaders of the ‘New Light’ movement, and the sermon was titled ‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God’. It would embody all the characteristics of sermons preached from New Light ministers: strong emotional appeal, descriptive language, and a message designed to get people back into the church from fear of eternal damnation. In those senses, it was a pretty standard sermon for the place and the time. Indeed, Edwards hardly got a peep out of his own congregation a few weeks before when he delivered the sermon there. But when he delivered it at Enfield, the congregation was so distraught and overwhelmed with emotion that they asked him to stop before he had finished it. He and the local minister then went into the congregation and tried to comfort individuals who were overcome with grief.

The most famous part of the sermon includes a vivid analogy involving a spider:

“The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider or some loathsome insect over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; His wrath towards you burns like fire; He is of purer eyes than to bear to have you in His sight; you are ten thousand times more abominable in His eyes as the most hateful venomous serpent is in ours. You have offended Him infinitely more than ever a stubborn rebel did his prince; and yet ’tis nothing but His hand that holds you from falling into the fire every moment.”(Sermons & Discourses 1739-1742, pp.411-412)

Thoughts & Sources

Believe it or not (and it’s probably hard to believe after that excerpt), Edwards was both a child of the Enlightenment and a follower of the empiricist philosophy of John Locke (1634-1704).

Edwards graduated from Yale University, which had been founded just in 1701. At the time it was a typical university, teaching a standard curriculum, comprised mostly of foreign language and Biblical studies. Since a major goal of early universities was to churn out ministers for the church, this was not all that unusual; Harvard had a similar curriculum. For Yale, however, this would all change in 1714 when Jeremiah Dummer, a London agent for the Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies, procured a major donation of books for the university. This collection was full of works of the new learning: the gift introduced the Yale students to the thought of John Locke as well as other Enlightenment thinkers, such as Clarke, More, Shaftesbury, Stillingfleet, Tillotson, Defoe, Bayle, even an English translation of the Qur’an.

The collection had two major effects: first, it introduced the Yale students to Enlightenment thought, and second, it caused a radical shift in the curriculum. The purpose of the university would no longer be the preparation of young men for the ministry; instead, it would now serve a much larger goal of a liberal education. One particular thinker who greatly benefited from the gift was the young Jonathan Edwards.

Edwards has been described as America’s first and most original philosophical theologian, and arguably the first American philosopher. He was a student at Yale when the Dummer books were donated. He graduated in 1720 and spent the next two years in graduate study there, taking a Master’s degree in divinity.

Edwards had always been drawn to the new learning. He was exposed to the ideas of Locke early on, and was fascinated by Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), a classic in empiricist epistemology and psychology. According to the American colonial historian Perry Miller, reading Locke’s Essay “had been the central and decisive event of [Edwards’] intellectual life… he read Locke and the divine strategy was revealed to him…God works through the concrete and the specific” (Jonathan Edwards, 1949, pp.52-3). Edwards embraced the philosophy of the new learning and believed it was a way for God to reveal himself more clearly to his followers. He found no inherent conflict in the doctrines of the new learning with those of Christianity. Instead, Locke and Newton fired his imagination; it may be said that Locke fueled his knowledge of philosophy, and Newton fueled his knowledge of science. Edwards found Locke’s concept of natural cause and effect attractive because it implied universal design, and he seemed ready to settle upon the Lockean concept of sensation as the source of what the mind knows.

Locke’s Empiricism

John Locke is considered the founder of the British ‘empiricist’ school of epistemology, which largely emerged as a counter to the European ‘rationalist’ school of Descartes et al. Empiricism believes that there’s no knowledge in the mind that does not have its origin in our sense experiences. In Locke’s own words, “Whence comes [to the mind] all the materials of Reason and Knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from Experience: In that, all our knowledge is founded” (Essay, II.I.2).

The general idea is that knowledge of the world originates from something external to us. True knowledge, that is, must be experienced. Locke spends the entire first book of his Essay attacking the idea of innate ideas – ideas you’re born with – which he viewed as an absurd notion: ideas are not in the mind when we are born, they are put there via experience, and so we must gather what knowledge we can from our perceptions. The mind is formed in a way that allows us to sort through our different experiences, store them, and retrieve them when they’re needed, recombining them mentally when necessary, and this is how learning occurs. This concept was a fundamental idea within Enlightenment thought, and played a heavy role within the scientific community during the Scientific Revolution, since for empiricists, observation and experiment are the primary vehicles to knowledge.

Edwards on Spiders

‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God’ was not Edwards’ only foray into the world of spiders. About twenty years earlier, on October 31, 1723, Edwards had also written about spiders, but with a different impression of them, to a different audience: “They are some things that I have happily seen of the wondrous and curious works of the spider. Although everything pertaining to this insect is admirable, yet there are some phenomena relating to them more particularly wonderful” (Scientific and Philosophical Writings, p.163). The younger Edwards had composed a letter that he hoped would be published by the Royal Society of London in their Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Jonathan’s father, Timothy Edwards, had earlier received a letter from Paul Dudley, who had published an article in the Philosophical Transactions on observations on plants in New England. Dudley finished the letter requesting further articles of anything from North America ‘observed in nature worthy of remark’. Edwards had jotted down a few observations two years earlier in his journal, ‘On Insects’, on the behavior of a particular type of ‘flying spider’ that existed in North America that had caught his eye. Edwards opens his letter to the Royal Society with the explanation that he’s noticed a certain kind of spider exhibiting an unusual behavior: it appears to fly ‘though they are wholly destitute of wings’. He says that he was very curious one day, so ventured into the forest and found a number of these little creatures and spent the entire day following them around and sketching notes about their behavior.

What Edwards discovered was interesting, but more important was what this event revealed about him. His observations reveal a complex thinker who is very much enamored with what nature has to offer. For Edwards, to experience nature was to experience the divine. “Resolving if possible to find out the mysteries of these their amazing works, and pursuing my observations, I discovered one wonder after another” (Writings, p.164). Thus, nature provides both knowledge and wonder. He ends the letter with the statement, “I don’t desire that the truth of it should be received upon my word” (p.166). His observations are not to be viewed as gospel. Instead, he encourages others to test the knowledge he has gained through these informal experiments. The fact that Edwards is performing observations and soliciting testing of them demonstrates the strong Enlightenment bent in his approach to knowledge, derived from Locke and the new learning. However, in keeping with the Puritan worldview, nature also has a purpose, and that purpose is revealed through God: “Wisdom of the creator in providing of the spider… so excellency secure to all their purposes… the exuberant goodness of the creator, who hath not only provided for all the necessities, but also for the pleasure and recreation of all sorts of creatures, even the insects” (p.167). This reveals the teleological or purposeful nature of the universe. God’s purpose is revealed not only through the Bible, but through the works of nature, and this revelation is available for all to discover. So for Edwards, science and religion work together in providing the truth to humans about God and their own natures.

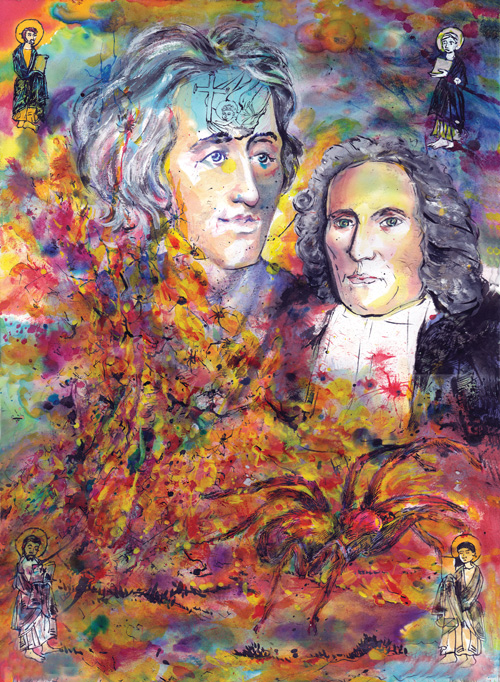

© John Locke And Jonathan Edwards By Venantius J Pinto 2021. To see more art, please visit behance.net/venantiuspinto

Lockean Spider Connections

What I find interesting about these two spider references, separated by almost twenty years and what appears on the surface as different goals, is the fact that both can be connected to the new learning, and to Lockean empirical philosophy specifically. Both texts can be interpreted as influenced by Lockean psychology and methodology.

The ‘Spider Letter’ provides probably the more obvious connections to Locke. Here Edwards first poses a question that has come about as a result of an ‘abnormal’ occurrence in nature, observed by numerous folks: How can spiders fly? He then goes about attempting to answer the question by using the scientific method of observation. It is also interesting that he goes out into nature to do so. Nature is seen as a viable source of information about the world, so the Bible is not the sole source of knowledge. Edwards is advancing an important empirical characteristic of knowledge here. Knowledge is gained through the scientific method and observation. Another important observation to take away from the ‘Spider Letter’, is the significance of the order and structure of the universe. An important element of science is that theories be falsifiable through testing them; and because the universe is ordered as well as observable, we can test our theory. Another aspect Edwards extrapolates from Lockean epistemology, is that observation connects all aspects of our being to the event. As well as intellectual knowledge, we feel the emotional connection: we receive pleasure from the experience of observing the spider and seeing the wonder of the universe. So Edwards’ experiment is not one of simple rational observation, but it also includes an element of emotion as well.

What might not be as clear are the influences of these Lockean ideas from the ‘Spider Letter’ upon ‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God’. But I think there are definite connections between the two documents. Edwards knows that intellectually speaking, his audience is aware of their inferiority to and dependence on God. This belief is part of the fabric of Puritan society. They’re told it from birth, and hear it weekly in sermons and various other places. But the goal of the sermons from the First Great Awakening was to get individuals to feel what it was that they already understood rationally. They knew they were sinners – but they needed to really know it. Via Locke, Edwards is well aware that until one experiences something, it will not strongly resonate as knowledge. I can see a plane crash on the news, and I can think to myself, ‘That could happen to me.’ However, I don’t get nervous till it hits home when I’m on a plane which suddenly drops about twenty feet in the air. It makes the airport safely, but I think, “We could have crashed, I could have died!” Similarily, in his ‘Sinners’ sermon, Edwards is trying to bring home peoples’ experience of their dependence on God’s grace by making the experience real, first, by using an analogy everyone has experience of – the spider – and second, by using visual language that clarifies to the listener the nature of their utter dependence. Edwards is making the audience feel the dependence that they already know rationally. Without this experience, there can be no real knowledge for them. Once the experience has registered, the mind can then organize and prioritize the information. Thus Edwards is drawing on Lockean psychology to hit home the spiritual message. (this point is derived from Kimnach, et al, Jonathan Edwards’s ‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God’: A Casebook, 2010).

Two works, separated by twenty years, written by one of the most influential Puritan theologians and philosophers during the First Great Awakening, both show the strong influence of Lockean thought. These documents reveal to us that religion and science are not inherently or necessarily in conflict with each other. If a thinker like Edwards can embrace both aspects into his Puritan worldview, it’s possible for the rest of us, too.

‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God’ is probably the most read sermon in the American literary canon, but without the proper context of the entire scope of his writings, it is easy to misinterpret both this sermon and Edwards’s overall philosophical and religious views.

© Dr John P. Irish 2021

John P. Irish teaches American Studies at Carroll Sr. High School in Southlake, Texas. He received a Doctorate in Humanities from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. He enjoys watching the different types of spiders that live in his backyard.