Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Interview

Steven Pinker

Steven Pinker is the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, and a popular writer on linguistics and evolutionary psychology. Angela Tan interviews him about politics, language, death, and reasons to be optimistic.

Hello Professor Pinker. In your book, The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), you discuss the decline of violence and how, despite appearances otherwise, our own era is by far the most peaceful in human existence. Are there unconscious biases we hold as a society that prevent our seeing a decline in violence?

It’s hard to make a generalization about a whole society. But you certainly can talk about the beliefs of an individual, and there are a number of cognitive biases that get in the way of our individually appreciating the ways in which violence has declined. In particular, there’s an interaction between a cognitive bias which Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman dubbed the availability bias, where we use images, narratives, and stereotypes from memory as a guide to estimating the probability and frequency of risk. Are you in danger of getting eaten by a shark if you go into the ocean? Well, if you can remember a shark attack from last year at that beach, you’re gonna stay out of the water, even if statistically you’re in greater danger of dying in a car accident when driving to the beach. There are a lot of distortions of risk that come from reliance on anecdotes. Then, when you think that the news is a non-random sample of the most dramatic, usually the worst things, happening on Earth at any given moment, there’s going to naturally be a tendency, given the availability bias, to think that the state of the world is described by the worst things happening at any given time. So while there certainly are disasters – and at this moment you and I are living through one in Ukraine, and one in Israel and Gaza, together with civil war in Ethiopia and Sudan – we tend not to think about the parts of the world that are at peace that used to be at war, such as Latin America. And there are no wars between countries in Southeast Asia. But we tend to overestimate the prevalence of war and violence based on a combination of what the news gives us and what the human mind latches onto. It’s only when you see the data and plot the number of deaths from war, from homicide, the amount of racism, and the amount of domestic violence, over time, that you can see whether violence really has increased or not. I argue in The Better Angels of Our Nature that when you look at those data, it is often surprising how many of them have decreased, despite the impressions we get from the media.

Photo © Christopher Michel Cmichel67 Creative Commons Licence 4.0

I find the metaphorization of illnesses interesting, especially when talking about historical biases. For example, tuberculosis was known as a disease of passion, even sometimes having class connotations as well, until Robert Koch discovered the bacteria responsible for it. The fantasies and cultural metaphors could be disassociated from the disease only when the cause was discovered . How do metaphors develop, and how are they weaponized?

Well, a lot of language is metaphorical. Because we aren’t born with vocabulary for everything we might want to talk about, we have to develop new vocabulary for new concepts. And the terms we use have to be transparent enough that other people know what we’re talking about. So if there’s a new virus, for example, if I just call it a blicket, or a dropsy, then I invent the necessary words, but no one knows what I’m talking about. So it’s natural to reach for a metaphor, then people can understand it in terms something similar, which works since people know it’s not literally true, but it would nevertheless give them a leg up in understanding the new term. For example, we talk in mixed metaphors a little bit when we talk about a meme ‘going viral’, when something gets passed on to others, and lots of people who receive it pass it on in turn, and so on, resulting in an exponential explosion. The metaphor is of exponential, viral, replication. That’s the way viruses work. And you understand that even if you don’t know the concept of exponential growth. Even if you don’t remember your high school math, the metaphor allows you to understand the concept.

In fact, when a metaphor becomes useful enough, it ceases to be metaphorical. People forget its origin and it just becomes a word in the language. It’s actually quite astonishing how much of our language is, or at least was, metaphorical. It’s actually not so easy to find language that wasn’t originally metaphorical.

This point about the metaphors we live by has been made by the linguist George Lakoff and the philosopher Mark Johnson. They point out that we can’t talk about intellectual arguments, for example, without using metaphors for war: “I attacked his argument, and he tried to defend it, but I won the argument: I defeated him!” And we talk about relationships like they’re journeys: “We’ve come a long way, but I think now we want to go our separate ways, I’m going to bail out.” One can say that, at this point, they’re no longer metaphors, they’re just words in the English language with understood meanings. And there’s probably a transition period in which some people do, and some people don’t, turn off their appreciation of the original image. But that’s one way new vocabulary items arise. And that’s why you get mixed metaphors, like ‘The ship of state is sailing down a one-way street.’ The politician who said that has kind of lost cognitive contact with the original image, and it’s just verbiage, which is what often happens with dull, turgid writing – a point I made in my writing manual, The Sense of Style (2014).

Historically, for example in Ancient Egypt, death was respected and seen as part of the process of life. But then, through shifts of society, death has turned into more of a statistical abstraction, segregated from life, where we don’t recognize the process of it anymore. How does the societal shift in the perception of death affect our mental well-being and view of life?

Well, we still do make a big deal about death: we have funerals and memorial services; we have burials or cremations; and we have headstones and plaques. So we don’t just treat it as an everyday occurrence. Yet as many commentators have said, we are separated from death in a way our ancestors weren’t. I think there are fewer open caskets. People don’t have the body in the living room of the household as often, and death is the physicality that is removed from us.

One’s own death always has been and still is a difficult thing for the human mind to process. But we love and interact with other humans; and it’s not just their body we interact with, but we treat them as an immaterial mind, as a locus of beliefs and desires, not just as a product of the activity of, or an organ of, the body. We can’t help but think of the mind as immaterial, and it also doesn’t make any sense intuitively for it to simply go out of existence – for a person’s experience, their emotions, their perceptions, to suddenly vanish.

Now when we adopt a more scientific mindset, we know that our consciousness is a product of brain activity; and that the brains, like all physical objects, doesn’t last forever, and when they stop functioning, the consciousness attached to it ceases. But intuitively, it’s very hard to wrap your mind around this, especially when it comes to yourself and your own consciousness. For your very awareness to cease existing is not something that you can easily grasp. On top of that, there’s our sheer cognitive impairment about, and durability of, death. And so, very naturally, we tend to invent or reinvent the notion of an afterlife or of reincarnation, or of the disembodied souls we depict as spirits in hauntings. There’s also a commitment we have to another person while they’re alive that we don’t like to think is easily turned off when they die. For example, when a loved one is not around, we don’t betray them or speak ill of them, even if we could get away with it. We adopt a commitment, a stance, and an ongoing attitude towards the person, where in they are precious and valuable to us, even if they can’t repay our favours. I mean, that’s what it means to be a decent person.

Now if you live your life committed to someone you love, someone that you respect, that’s not something you can just turn on and off like a switch. Well, when the person is gone, you can’t just suddenly pretend that they don’t matter. I mean, if you could do that when they’re dead, you could have done that when they were alive, and that would have meant you were certainly less committed as a friend, an ally, or a partner. And so, since we can’t easily flip a switch and turn off our feelings toward a person once they’re dead, this means that we treat the dead in a way that’s commensurate with the way we treated them when they were alive. And so we get many rituals, for example the Hispanic Day of the Dead, where you leave out food to attract the soul of the person, and you continually treat them as someone you love, even though they are no longer around. I think that kind of mindset is very common. And it’s just part of the psychology of emotional and personal commitment.

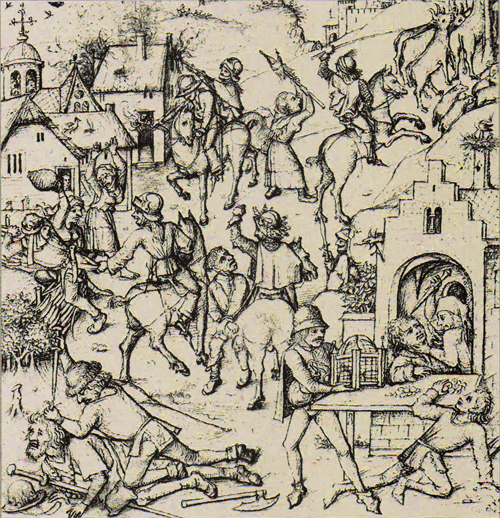

The ‘good old days’: ‘Mars’ from Das Mittelalterliche Hausbuch, c.1480

Are there any specific points in your research that have had a profound and lasting impact on your moral outlook, or even your relationship with your body?

A couple. Learning from psychology, including evolutionary psychology, the extent of our self-deception, especially about our own virtue and competence, and the fact that we lie to ourselves in order to be more effective liars to others, means that I now often do think twice, and check myself. And I don’t take my own intuitions at face value, because they might be a kind of PR campaign by my subconscious to make me look good or deserving of other people’s attention or favours.

Actually, I’m in a privileged position as a psychologist: almost everything I study I make use of in my everyday life. Everything from perception – ‘Why do I find a sunset beautiful?’; ‘Why do I find a face beautiful?’ – to relationships between the sexes. I don’t think we start off as blank slates, where men and women are psychologically indistinguishable, for example, and so I reflect on what makes men and women react to things differently. I even reflect in my own interaction with women, to remind myself that what seems perfectly natural to me may not seem perfectly natural to a typical woman. I think factoring in the fact that we don’t all react to the same thing in the same ways can increase understanding across the gender line.

On a larger scale, I’m influenced by the fact that I’ve exposed myself to various data on human progress: that we kill each other less, we have less torture, we have less domestic violence, we have less homicide, less capital punishment, and how we have more or less eliminated human sacrifice as a species, and have eliminated legal slavery. All these are progress, if that word has any meaning whatsoever. And all this has strengthened in me the commitment, the hope – the reasonable expectation – that further progress is possible, even though I believe that there’s such a thing as human nature, that I don’t think we’re blank slates. I don’t think we’re ‘noble savages’, though: I think we’ve got a lot of nasty, ugly traits, thanks to evolution, but I also think that we have some means to overcome them, as evidenced by the fact that a lot of our bad behaviors have gone down in frequency throughout history. And the fact that we have been able to, as Abraham Lincoln put it, bring out our better angels, means that it’s not romantic or utopian or hopeless to work for more progress to solve our problems – to expand human rights, human dignity, human flourishing. Looking at the data, I just know that that’s possible.

As a high school student, I’m concerned about the growing polarisation of thought and discourse, which sometimes leads to violence. What advice would you give young people who would like to mitigate the polarization, and promote more constructive and peaceful conversations in our communities?

Well, I think even posing the question is a good start, in terms of being aware that polarisation is a problem. Polarisation comes from mutual overconfidence; from knowing that one’s own opinions are correct without examining them. What we should foster is a set of attitudes that remind each of us of our own fallibility, that we’re probably wrong about most things, just because most people are wrong about most things. And we’re all human: we’re not angels, and we’re not gods. We also need to know that we are all subject to biases, such as ‘tribalistic’ or ‘my side’ bias, where we always think our own side is correct. Even when it feels on the inside that those other people are stupid and evil, and that we all have halos, it would be good to be able to step outside ourselves and be aware of that bias – to think, well, maybe the other person does have a point. This is learning to see your own opinions as hypotheses that have to be strengthened or weakened as evidence comes in: that they’re hypotheses to be discarded if the evidence changes, rather than commitments showing how steadfast, courageous, and honourable you are as a person. That’s not the way you should treat your beliefs. Rather, your beliefs should be things you hold tentatively, depending on how strong the evidence is, and you should be prepared to give them up to avoid fallacies like attacking the person instead of a position, or certain other fallacious habits of thought that unfortunately have become more common, especially in younger generations.

A point made by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in The Coddling of the American Mind (2018), is that that advice is almost the opposite of some prescriptions taken from cognitive behavioural therapy which say that you should trust your feelings, as many people now believe. Bad idea. Rather, you should learn how to discount your feelings. In fact, however, one of the things you’re advised to do in cognitive behaviour therapy is to control your emotions and not let your emotions carry you away. Furthermore, don’t demonize other people; don’t think of the world in simplistic terms of good and evil; and don’t believe that progress consists in victims, the good people, turning the tables on their oppressors, the bad people. Rather, everyone has some good and bad in them. We want to foster the ideals, not punish the people. And we also want to be able to look at our experiences and think that we’ve learned from them. Not everything’s a trauma, and every time you encounter an opinion that makes you feel uncomfortable, don’t think, “Are you harmed? Are you hurt?” Quite the contrary. Being exposed to opinions that you don’t hold makes your own opinions stronger. If the alternative opinions are right, they might lead you to get rid of your own. And if the alternative opinions are wrong? Then that’s ultimately what we want to find out.

• Angela Tan is a student at York House School in Vancouver, B.C. She is interested in the intersection of ethics and education. As a host of the oxfordpublicphilosophy.com podcast, she hopes to bridge polarization through dialogue.