Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Philosophers by Steve Pyke

Constantine Sandis looks philosophically at Steve Pyke’s photos of philosophers.

“After a certain age, every man has the face he deserves,” claims Jean-Baptiste Clamence, the self-proclaimed ‘judge-penitent’ in Albert Camus’ final novel, The Fall. A century earlier, Abraham Lincoln had decided that the all-important age was forty years, reportedly refusing to appoint someone to a post in his government because he didn’t like his appearance. Aged forty-six and on his deathbed, George Orwell more prudently proclaimed that it was at fifty that “every man has the face he deserves.” None of them seemed to have a view about women. Nor did any of them consider the altogether more plausible suggestion that it is our parents, partners, employers and government who have the most to answer for when it comes to our faces, and that, by the same token, we might ourselves be held a little accountable for the faces of those we share our lives with.

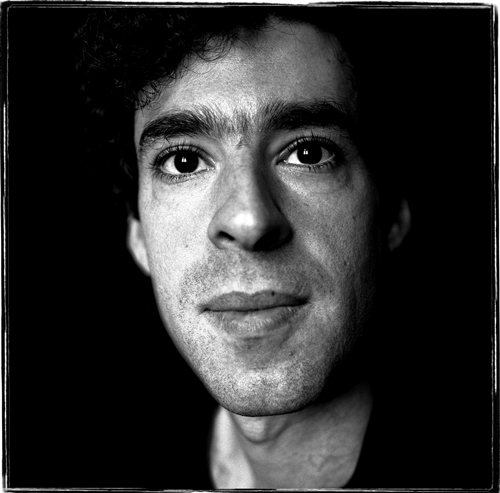

Delia Graff Fara

All philosopher images © Steve Pyke 2012 from the book Philosophers. Please visit www.pyke-eye.com.

So what can we say about the faces in this book? Philosophers, by the portrait photographer Steve Pyke, MBE (a contributing photographer at The New Yorker and Vanity Fair since 1998), is a book of photos of philosophers accompanied by short quotes or captions. Most of the hundred-odd philosophers pictured are old enough to be responsible for their faces by Orwell’s standards, but it is good to also see some younger faces this time around, including Joshua Knobe, as well as Delia Graff Fara, Elizabeth Harman, Jason Stanley and Robert Williams.

To misquote Ansel Adams, there are three people in every portrait photograph: the subject, the photographer, and the viewer. Photographers are unarguably at least partly responsible for how their subjects are perceived, regardless of whether or not they deserve to be seen in that way. Individual captions or even titles further affect the perception we would otherwise have had of any photographs (hence the pull of the ‘prof or hobo?’ and ‘supporter or deporter?’-type quizzes). This last hypothesis can easily be tested by swapping the dust cover of this volume with that of Pyke’s other wonderful collection Astronauts. Those suffering from the standard stereotype of what philosophers look like would also do well to conduct a general image search under the word ‘philosopher’ and compare the results to the pictures posted on the blog at looksphilosophical.tumblr.com. A recent study conducted by a team of experimental psychologists and philosophers (including the aforementioned Joshua Knobe, photographed by Pyke in a T-shirt for this book) even revealed that we more readily attribute intellectual and moral capacities to fully-clothed subjects than we do to subjects who are even partially naked. It would be interesting to test to what degree the same is also true of age, facial hair, different styles of garment, and so on.

Appearances can be deceptive. In a recent interview for an exhibition of the photographs that comprise this book, Pyke said of his subjects that he “noticed that whilst they can seem socially to be very tolerant people, in debate they were less so.” And in the age of Photoshop, we can no longer place more trust in photographs than we can in paintings. In neither case should we trust ourselves much either, for it is impossible to clearly distinguish what is contained in a picture from what we project onto it. (As David Hume demonstrated, art is not unique in this. Moral, causal, historical and religious judgements also frequently involve projection.) Paradoxically, it is always the picture that has the last word, to use Derrida’s playful way of suggesting that a picture always itself remains the final authority on whatever we choose to say about it.

Jason Stanley

Philosophical Reflections

Philosophers is Pyke’s second collection of portraits of largely recognizable faces from academic philosophy, and despite having the same title as his first, is not a new edition of it, but rather a sequel to the original 1993 collection (large prints of which feature prominently in the otherwise uninspired 2004 film of Patrick Marber’s play Closer). As with its predecessor, there are no subjects from outside of the US, UK, and France, and the proportion of women included remains at approximately twenty percent. This figure is an accurate reflection of the regrettable current state of the profession, rather than Pyke’s take on it.

The new book seems more self-aware as a whole – complete with an introduction by the philosopher of aesthetics Arthur C. Danto, and an interview of the artist by Jason Stanley. The portraits included are all shot in black and white – although the spectacular contact sheet which formed a mural in the accompanying exhibition revealed that Pyke experimented with colour shots too. Danto and Stanley both claim that the greatest aesthetic difference between the two series of portraits, is that the new ones have a black background, making it seem as if each philosophers is emerging from out of the darkness – yet the original volume also had considerably more photographs with dark backgrounds than white ones, and white backgrounds are not altogether absent from the new set. At any rate, the most successful images are those in which the subject is in stark contrast with the background, regardless of colour. Set thus, the Pyke-eye is at its most revealing when it zooms in real close.

In the introduction to his 1989 collection of essays The Examined Life, the philosopher Robert Nozick wrote that “no photograph of a person has the depth a painted portrait can have,” arguing that unlike a painting, a photograph is a mere ‘snapshot’ of “one particular moment of time and what the person looked like right then.” Pyke’s collection proves just how wrong Nozick was to suppose that a picture of a person in a moment of time could not reveal a lifetime’s worth of traits, beliefs, emotions and aspirations.

It is possible that Nozick himself came to appreciate this in due course. Whilst he refused in 1990 to be photographed for Pyke’s original project (having issues with photography and representation), he changed his mind and agreed to it in 1992. Unfortunately he became gravely ill, and died before he could be photographed for that visual overview of twentieth-century analytic philosophy.

Pyke asked his subjects to send in a few lines – about themselves, about philosophy, or about both – which are published alongside each picture. It is revealing to compare the content of these with those in the 1993 book, as they collectively reveal a small yet steady change in the philosophical climate. Whereas many of the original paragraphs concentrated on the specific fields of interest of each subject, the later set is tellingly marked by a tendency to wax lyrical on philosophical methodology, and on the relation of philosophy to other subjects, including history, linguistics, psychology and neuroscience. The new set of philosophers compare philosophy to poetry, sculpture, construction, juggling, geometry, engineering and sleuthing, and associate it with clarity, universality, reflection, questioning, knowledge, truth, demystification, transcendence, deep common sense, scepticism, illumination, perception, anti-authoritarianism, curiosity, explanation and understanding, among other things. Gone is the sense of a common method or goal. This is no bad thing, for without both openness and doubt, philosophy turns to rigid dogmatism. There is more excitement in the air; but one also senses a previously absent uncertainty regarding the future of the subject. The overall impression is of a discipline once secure in its self-image undergoing a serious paradigm shift. Some might take this to indicate the academy in peril; others will see it as a sign that twenty-first-century philosophy has broken free of its recent chains and flown back to the methodological pluralism of the ancients. Either way, philosophers could not have hoped for a better portrait artist than Steve Pyke.

© Constantine Sandis 2012

Constantine Sandis is a Reader in Philosophy at Oxford Brookes University and the author of The Things We Do and Why We Do Them (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

• Philosophers by Steve Pyke, Oxford University Press, 2011, 224pp. ISBN-13: 978-0199757145.

• Signed limited editions of both the original and new volumes of Philosophers are available through Steve Pyke’s New York studio. Go to www.pyke-eye.com.

(A shorter version of this review appeared in the Times Literary Supplement of April 5th, 2012.)

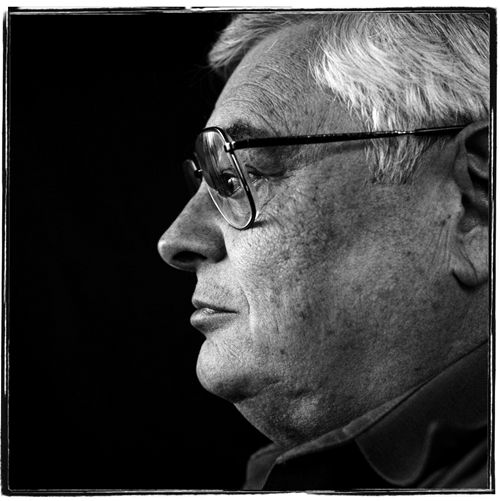

Jerry Fodor in Philosophers

Jerry Fodor

“To the best of my recollection, I became a philosopher because my parents wanted me to become a lawyer. It seems to me, in retrospect, that there was much to be said for their suggestion. On the other hand, many philosophers are quite good company; the arguments they use are generally better than the ones that lawyers use; and we do get to go to as many faculty meetings as we like at no extra charge.”

– Jerry Fodor, 20th March 2003, from Philosophers