Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527)

Graeme Garrard on one of the few writers whose name has become an adjective.

Five centuries ago this year, at the height of the Italian Renaissance, an unemployed former civil servant sat in the study of his modest country farm in the tiny village of Sant’Andrea just south of Florence, pouring everything he knew about the art of governing into a long pamphlet. He hoped that by making a gift of it to Lorenzo de Medici, the new ruler of Florence, it would win him back the job he passionately loved. But it was ungraciously brushed aside by a prince who had little interest in the musings of an obscure, exiled bureaucrat on the principles of statecraft. The pamphlet was eventually published in 1532, five years after Niccolò Machiavelli’s death, as Il Principe (The Prince).

Machiavelli’s Devotion

For fourteen years Machiavelli had worked tirelessly and with utter devotion for his native city of Florence as a diplomat and public official, travelling constantly on its behalf to the courts and chancelleries of Europe, where he met Popes, princes and potentates. He witnessed the political life of the Italian Renaissance first-hand and up-close. It was an age of very high culture and very low politics, of Michelangelo and Cesare Borgia – both of whom Machiavelli knew personally. An intensely patriotic Florentine, he spurned an offer to become an advisor to a wealthy and powerful Roman nobleman at the generous salary of 200 gold ducats because he wanted to serve his native city. He had recently worked as Head of the second chancery, Chancellor of the Nine (the body that oversaw Florence’s militia), and Secretary to the Ten that supervised the city’s foreign policy. Not that this made any difference to the Medici family, who in 1512 had overthrown the Florentine republic Machiavelli had so loyally served. Machiavelli was promptly dismissed, arrested, tortured, and exiled from his native city. The torture, six drops on the strappado – in which he was raised high above the ground by his tied arms, dislocating his joints – he took admirably well, even writing some amusing sonnets about it. He only narrowly escaped execution; then a general amnesty was granted after Lorenzo’s uncle was elected Pope Leo X in March 1513.

Machiavelli appeared to hold few grudges. Being tortured was fair play in Renaissance politics, and he would advocate far worse in The Prince. But being forced out of the life of politics that enthralled him, and banished from the city he loved ‘more than my own soul’ was almost more than he could bear. He confessed to his nephew that, although physically well, he was ill ‘in every other respect’ because he was separated from his beloved native city, and he complained to a friend that ‘I am rotting away’ in exile. He desperately missed the excitement, risks and stimulation of city life, and was bored senseless by the dreary routines of domestic life. To fend off the monotony he spent his days reading and writing, chasing thrushes, and playing backgammon with the local inn-keeper. Although living only a tantalizingly short distance from the hub of Florentine government, the great Palazzo Vecchio (where a bust of Machiavelli stands today), Machiavelli might as well have been living on the dark side of the moon. Although he enjoyed a partial rehabilitation near the end of his life, when he was again working at the Palazzo Vecchio, it was in the very limited role of secretary of the Overseers of the Walls of the City, responsible for rebuilding and reinforcing Florence’s defences.

In a letter written shortly before his death he signed himself “Niccolò Machiavelli, Historian, Comic Author and Tragic Author.” According to a popular legend, he had a dream while on his deathbed in which he chose to remain in Hell discussing politics with the great pagan thinkers and rulers of antiquity rather than suffering the tedium of Heaven.

Machiavelli’s Ethics

Machiavelli was not a philosopher in the narrow sense of the word, or even a particularly systematic thinker, and The Prince, which was written hastily, is not a rigorous philosophical treatise. Yet because of its many penetrating insights into the nature of political life in general, and the striking boldness and originality of Machiavelli’s thoughts on, for example, the nature of power or the relationship between ethics and politics, it has long enjoyed an exalted place in the small canon of great works in the history of political philosophy.

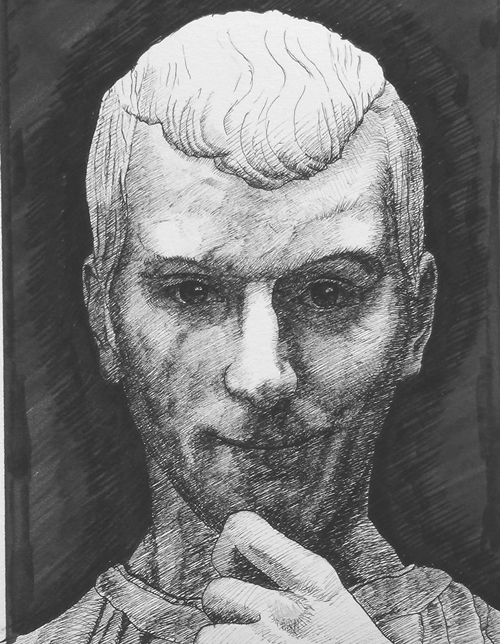

Portrait of Machiavelli © Darren McAndrew 2013

The popular image of Machiavelli is of a brutal realist who counseled rulers to cast aside ethics in the ruthless pursuit of power. This view is not without some basis in The Prince, which condones murder, deceit and repression as essential means for rulers to retain their grip on power. Machiavelli says repeatedly that given that men are “ungrateful, fickle, liars and deceivers, fearful of danger and greedy for gain,” a ruler is “often obliged not to be good.” So it is vital for statesmen not only “to learn how not to be good” but also “to know when it is and when it is not necessary to use this knowledge.” History is littered with failed politicians, statesmen and rulers who lost power either because they did not appreciate this hard fact of political life, or were unwilling to act on it when they did. For Machiavelli, being insufficiently cruel is a sure path to eventual political defeat – which in Renaissance Italy was often the path to an early grave as well. What was shocking about The Prince was not the deeds he recommended, which were common enough in the politics of the day, but the brazen directness with which Machiavelli advocated expedients such as, for example, wiping out the entire family of a ruler.

However, Machiavelli does not simply argue that political expediency requires that ethics be set aside. Rather than being amoral or immoral, as commonly assumed, Machiavelli was an ethical consequentialist, who thought that the end justifies the means. He argued that, in the normally brutal world of real politics, rulers are often forced to choose between two evils, rather than between two goods or between a good and an evil. This is the classic dilemma of political ethics that is often referred to as ‘the problem of dirty hands’, in which politicians are often confronted with situations in which all of the options available to them are morally repugnant. In such tragic circumstances, choosing the lesser evil over the greater evil, however cruel and repugnant in itself, is the ethically right thing to do. In his Discourse on Livy, written shortly after The Prince, Machiavelli states this problem and his attitude towards it very succinctly: “if his deed accuses him, its consequences excuse him. When the consequences are good, as were the consequences of Romulus’s act, then he will always be excused.” Indeed, a hard-nosed ruler who is willing to commit evil acts (deception, torture, murder, for example) in order to prevent even greater evil may deserve moral admiration and respect. The truth of this was made apparent to Machiavelli when he visited the town of Pistoia in Tuscany in the opening years of the sixteenth century, which visit he recounts in The Prince. The town was torn between two rival families, the Cancellieri and the Panciatichi, and the conflict risked escalating into a bloody civil war, so the Florentines sent Machiavelli in to broker a settlement. When he reported back to Florence that things had gone too far and that they should step in forcefully, his advice was ignored for fear that it would lead to a reputation for brutality. Machiavelli’s fears were soon realised when further talks failed and Pistoia degenerated into chaos, causing much more violence and destruction than if the Florentines had taken his advice and intervened harshly, which would have been the lesser evil. As the philosopher Kai Nielsen has put it, “where the only choice is between evil and evil, it can never be wrong, and it will always be right, to choose the lesser evil.”

Machiavelli’s Princely Virtues

One of Machiavelli’s most important innovations in The Prince is his redefinition of ‘virtue’, which he equates with the qualities necessary for political success – including ruthlessness, guile, deceit, and a willingness to occasionally commit acts that would be deemed evil by conventional standards.

The classical ideal of virtue Machiavelli rejected was expressed by Cicero (106-43 BCE), whose De officiis (On Duties) was read and copied more frequently during the Renaissance than any other single work of classical Latin prose. Cicero argued that rulers are successful only when they are morally good – by which he meant adhering to the four cardinal virtues of wisdom, justice, restraint and courage, as well as being honest. For Cicero, the belief that self-interest or expediency conflicts with ethical goodness is not only mistaken but deeply corrosive of public life and morals. In Renaissance Europe this idealistic view of politics was reinforced by the Christian belief in divine retribution in the afterlife for the injustices committed in this life, and the cardinal virtues were supplemented by the three theological virtues of faith, hope and charity.

Machiavelli believed that the ethical outlooks of both Cicero and Christianity were rigid and unrealistic, and actually cause more harm than they prevent. In the imperfect world of politics, populated as it is by wolves, a sheepish adherence to that kind of morality would be disastrous. A ruler must be flexible about the means he employs if he is going to be effective, just as the virtue of a general on the battlefield is a matter of how well he adapts to ever-changing circumstances. Machiavelli asserts in The Prince that a ruler “cannot conform to all those rules that men who are thought good are expected to respect, for he is often obliged, in order to hold on to power, to break his word, to be uncharitable, inhumane, and irreligious. So he must be mentally prepared to act as circumstances and changes in fortune require. As I have said, he should do what is right if he can; but he must be prepared to do what is wrong if necessary.” By doing ‘wrong’, he means in the conventional sense of the word – but, in reality, it is right, even obligatory, sometimes to commit acts that, while morally repellent themselves, are nonetheless good in their consequences because they prevent greater evil. That is why Machiavelli calls cruelty ‘well-used’ by rulers when it is applied judiciously in order to prevent even greater cruelty. Such preventive cruelty is ‘the compassion of princes’– the cruelty that saves from cruelty.

Machiavellian virtue is harsh and realistic, appropriate for the kinds of rapacious, predatory creatures who populate the political world as Machiavelli saw it. It is also masculine, just as fortune is feminine (‘lady luck’), and usually fairly benign. However, in Machiavelli’s hands she becomes a fickle and malevolent goddess who delights in upsetting the plans of men and leading them into chaos and misery. However, whereas Christianity preached resignation to the whims of fortune, Machiavelli argued that a virtuous ruler could impose his will on it, at least to some degree. The Prince notoriously depicts fortune as a woman whom the vir, the man of true manliness, must forcibly subdue if he is to impose his will on events.

Machiavelli was one of the first writers in the West openly to state that dirty hands are an unavoidable part of politics, and to accept the troubling ethical implications of this hard truth without flinching. Politicians who deny it are not only unrealistic, but are likely to lead citizens down a path to greater evil and misery than is necessary. That is why we ought to think twice before condemning them when they sanction acts that may be wrong in a perfect world. A perfect world is not, and never will be, the world of politics.

© Dr Graeme Garrard 2013

Graeme Garrard is Reader in Politics at Cardiff University.