Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Trying Herder

Dale DeBakcsy listens to the lost voice of the Eighteenth Century’s greatest Twenty-First-Century thinker.

Of all the crimes a late eighteenth century German cultural thinker could commit, none carried a stiffer sentence than Not Being Goethe. Klopstock, Möser, Süssmilch, Reimarus, Herder… all names blasted out of our common cultural memory by their proximity to the towering poet of Weimar. Yet while there probably isn’t anybody weeping torrents over the loss of Süssmilch, the obscurity of Johannes Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) is actually rather tragic. Consistently two centuries ahead of his time, his ideas about linguistics and comparative history had to wait until the twentieth century for a rebirth, while his reflections on cognition are shockingly prescient of developments in modern neuroscience. How was it that such an original and deep thinker became so utterly lost to us?

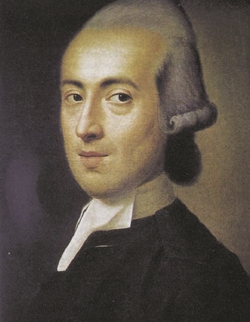

J.G. Herder

The real problem is that he wasn’t so much lost as dismembered. The whole Herder is a creature hardly seen in nature before it is set upon and harvested for organs by whatever academic faction happens to be hungry for provenance at the time. The Romantics took his stance against Pure Reason, chopped it up into a few ringing phrases, and used it as a part of their more general campaign against the Enlightenment. And so the nineteenth century came to see Herder as a great irrationalist, in spite of his many writings praising reason and science as crucial paths to the self-realization of humanity. The twentieth century, when it bothered to notice him at all, saw only his comments about the cultural specificity of language, and heralded them as precursors of Quinean relativism, conveniently ignoring the parts of his work which stress the unifying nature of human cognitive processes. What has come down to us, then, have been a series of partial Herders hitched to the wagons of fleeting philosophical and cultural movements – caricatures so broadly drawn that they understandably failed to outlive their revivers. Here I want to sketch an image of Herder worth remembering.

Man Manifest

Johannes Herder was born in Mohrungen, East Prussia (now in Poland), a town of about a thousand souls, known for the production of cattle and theologians. Shaking the dust of that small town from his boots, he ended up, at the tender age of eighteen, in Königsberg. Königsberg was the place to be for a budding thinker, offering the chance to study not only under the great champion of holism, Johann Georg Hamann, but also under a promising up-and-comer by the name of Immanuel Kant.

Herder’s first writings were in the field of literary criticism, and flew in the face of pretty much every major school of thought at the time – setting a life-long precedent of rubbing the philosophical establishment the wrong way. While Enlightenment thinkers were seeking to find universal laws for drama and aesthetics, Herder came out hard for evaluating each work against the historical standards and practices of its time and culture. Rather than denigrating Shakespeare for not being Voltaire, he argued, oughtn’t we consider what his work means in the context of Elizabethan society and concerns? Common sense now, perhaps; but revolutionary stuff for the Enlightenment with its mania for universal systems.

More astounding still are the thoughts he put to paper in response to a Berlin Academy essay competition of 1769. The theme was the origin of language, a topic up to that time dominated by two warring camps: the first held firmly to the idea that language must be of divine origin, while the other held that it is already present in animals, evident in the growl of the lowliest town mutt. Herder’s argument ran counter to both these schools, and in the process very nearly created modern linguistic and neural theory in eighteenth century Prussia.

For Herder, language was a distinctly human phenomenon, born from man’s unique cognitive practices: language is in the very structure of how we approach and perceive the world. Moreover, in a move that anticipated discoveries in neuroscience made only within the last half century, Herder identified reflection, networking, and plastic association as the hallmarks of human cognitive life. What separates man from animals, Herder believed, is man’s capacity for reconsidering ideas (reflection), for using multiple parts of his mind in evaluating a passing idea (networking), and for holding onto an idea while considering its relation to other facts of the world (plastic association). Some poetic turns of phrase aside, Herder’s focus on the centrality of reflection belongs solidly in the twenty-first century: “Man manifests reflection when the force of his soul acts in such freedom that, in the vast ocean of sensations which permeates it through all the channels of the senses, it can single out one wave, arrest it, concentrate its attention on it, and be conscious of being attentive. He manifests reflection when, confronted with the vast hovering dream of images which pass by his senses, he can collect himself into a moment of wakefulness and dwell at will on one image, can observe it clearly and more calmly” (Essay on the Origin of Language, 1772). Herder found the root of language in these uniquely human capacities, and in doing so, somewhat astoundingly, described for us the functions of the lateral prefrontal cortex before it had even been discovered. Fast forward two hundred and fifty years, and neuroscience is just now showing us that the possession of a prefrontal cortex in primates is what allows working memory to function – holding an idea and considering its connections to other ideas without being externally stimulated to do so – and that, further, this area of the brain is where our linguistic processing modules are found.

Positing working memory rather than pure reason as the root of human language and even humanity was a stroke of genius too far ahead of its time to succeed; but Herder didn’t stop there. Facing an intellectual culture that was trying to split human thought and action into the purely reasonable or the purely emotional, Herder replied that, “If we have grouped certain activities of the soul under certain major designations, such as wit, perspicacity, fantasy, reason, this does not mean that a single act of mind is ever possible in which only wit or only reason is at work; it means no more than that we discern in that act a prevailing share of the abstraction we call wit or reason” (Origin of Language). It took humanity two and a half centuries to come back to the truth that you can’t wall off parts of the mind from each other. As we’ve since come to discover, even our simplest thoughts or actions require the networking of multiple brain centers and functions in exquisite unison, crafted by the neural connections determined by genetics and experience.

The Flow of Language

The influence of experience was a theme to which Herder would return to repeatedly in his historical and linguistic work. In a move that anticipated Julia Kristeva’s semiotic theory, he argued strongly that words must not be considered purely from the point of view of their logical structure, but also in terms of their rhythmic, emotional, and other experiential elements. As he rather fancifully put it, “This weary breath – half a sigh – which dies away so movingly on pain-distorted lips, isolate it from its living helpmeets, and it is an empty draft of air” (Origin of Language, Section One). The sound and rhythm of language, which hold so much of the meaning of words in their spoken contexts, are largely left behind on the printed page. And as we lose touch with the situation in which our words were originally formed, so do our words taste increasingly artificial on our lips. They become the worn-beyond-recognition coins that Nietzsche would make famous a century later. This was particularly a problem, Herder saw, for his own profession as a preacher: “The most meaningful sacred symbols of every people, no matter how well-adapted to the climate and nation, frequently lose their meaning within a few generations. This should come as no surprise, for this is bound to happen to every language and to every institution that has arbitrary signs as soon as these signs are not frequently compared to their objects through active use… as soon as [priests] lost the meaning of the symbols, they had to become either the silent servants of idolatry or the loquacious liars of superstition. They did become this almost everywhere, not out of any particular propensity to deception, but out of the natural course of things” (Ideas Towards a Philosophy of History, 1784).

Such considerations of the particularity of linguistic and cultural practice made Herder a fierce champion of the right of each nation to find happiness through its own means, to be evaluated on its own terms, and to hold with whatever religious notions make sense in its own language and tradition. He despised colonialism and the forcible conversion of native people. He would have none of any system of classification which attempted to posit a scale of perfection with modern humanity sitting regally at the top. Just as Shakespeare was not Eurpides Done Wrong, neither is India merely Ancient Greece Done Wrong. To posit a happiest or best civilization is to establish a scale of comparison, whereas in fact there are just people working after whatever satisfaction their situation can afford them. “No one in the world feels the weakness of generalizing more than I… Who has noticed how inexpressible the individuality of one human being is – how impossible it is to express distinctly an individual’s distinctive characteristics? Since this is the case, how can one possibly survey the ocean of entire peoples, times, and countries, and capture them in one glance, one feeling, or one word? What a lifeless, incomplete phantom of a word it would be! You must first enter the spirit of a nation in order to empathize completely with even one of its thoughts or deeds” (Another Philosophy of History, 1774). And lest his contemporaries believe they had a real chance to fully understand and therefore judge a culture by reading about it in an open and empathetic spirit, Herder gleefully yanked the rug away by pointing out the utter hopelessness of genuine translation: “Those varied significations of one root that are to be traced and reduced to their origin in its genealogical tree are interrelated by no more than vague feelings, transient side associations, and perceptional echoes which arise from the depth of the soul and can hardly be covered by rules. Furthermore, their interrelations are so specifically national, so much in conformity with the manner of thinking and seeing of the people, of the inventor, in a particular country, in a particular time, under particular circumstances, that it is exceedingly difficult for a Northerner and Westerner to strike them right” (Origin of Language, Section Three). You will always miss something, and there is no way of knowing whether that something was insignificant, or was, after all, the most important part of the concept you were trying to nail down.

Which brings us to George Orwell. Because, not content with establishing a network theory of cognition, a semiotic theory of language, and a comparative approach to historiography and literature centuries before their time, Herder, like Orwell, also analyzed the role of linguistic association in mass politics – before mass politics really even existed. Take a look at this, written in 1772:

“What is it that works miracles in the assemblies of people, that pierces hearts, and upsets souls? Is it intellectual speech and metaphysics? Is it similes and figures of speech? Is it art and coldly convincing reason? If there is to be more than blind frenzy, much must happen through these; but everything? And precisely this highest moment of blind frenzy, through what did it come about? – Through a wholly different force! These tones, these gestures, those simple melodious continuities, this sudden turn, this dawning voice – what more do I know? – They all… accomplish a thousand times more than truth itself… The words, the tone, the turn of this gruesome ballad or the like touched our souls when we heard it for the first time in our childhood with I know not what host of connotations of shuddering, awe, fear, fright, joy. Speak the word, and like a throng of ghosts those connotations arise of a sudden in their dark majesty from the grave of the soul: They obscure inside the word the pure limpid concept that could be grasped only in their absence.” (Origin of Language, Section One).

This is politics as the art of using tone and rhythm to recall primal past experiences and therefore elicit the desired present emotions quite irrespective of the actual content of the words being spoken. Somehow, sitting in an autocratic Prussian state almost devoid of mature political institutions, Herder managed to piece together the notion of subliminal messaging and its potential use in mass media politicking.

This isn’t to say that Herder was always so prescient or revolutionary. His explanation of suffering is little different from the colossally unconvincing argument St Augustine trotted out thirteen centuries earlier. But these half-hearted gestures pale next to the monumental leaps of imagination with which he enriched the late eighteenth century, and, if we are willing, with which he will enrich our own. Many of his ideas we have since rediscovered, but loaded down with such onerous and generally unenlightening jargon (I’m looking at you, Carl Jung) that the scope and profundity of these ideas have been drastically and tragically narrowed. A return to the source is in order – the whole Herder: often fanciful, sometimes deliciously naïve, but never more relevant than at present.

© Dale DeBakcsy 2013

Dale DeBakcsy is a contributor to The New Humanist and The Freethinker and is the co-writer of the twice-weekly history and philosophy webcomic Frederick the Great: A Most Lamentable Comedy.