Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Chamfort (1740-1794)

Martin Jenkins looks at the life of a wry observer of society, cut short by that society’s revolutionary turmoil.

Montaigne invented the essay. Another Frenchman, La Rochefoucauld, invented the maxim: the presentation of profound ideas in short self-standing statements. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche used that form extensively; but most practitioners seem to have been French. The French call them moralistes, which, like its English equivalent, implies commentators on the moeurs, or customs, of society.

What is the attraction of expressing ideas as aphorisms, usually without argument, inviting the reader to accept them as ‘self-evident truths’? One suggestion is:

“Maxims, axioms, are, like summaries, the work of people of spirit [or of ‘wit’], who, it seems, have laboured for the benefit of mediocre or lazy minds. The lazy reader takes on a maxim, which releases him from having himself to make the observations which led the author of the maxim to the conclusion which he shares with the reader. The lazy and mediocre person thinks himself released from going any further…”

The author of this typically cynical observation was the last of the great French moralistes, Chamfort.

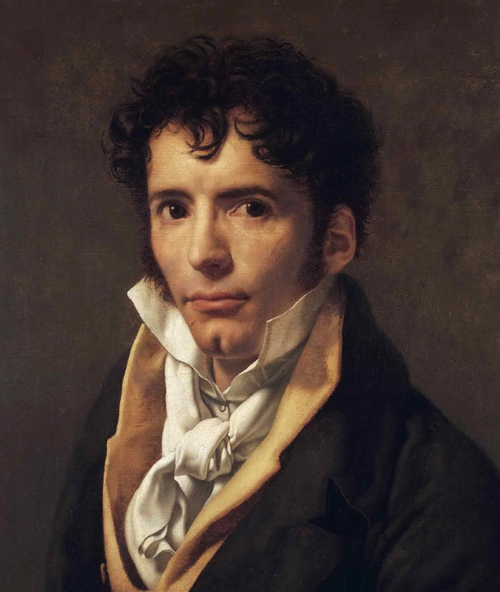

Chamfort, 1767, by Anne Louis Girodet de Roucy Trioson

Who was Chamfort? Nobody knows for certain. His birth was registered in 1740 at Clermont-Ferrand as Sébastien-Roch Nicolas, son of François Nicolas, grocer, and his wife, Thérèse Croiset. There were, however, suggestions that he was really the illegitimate child of a churchman; and his closest friend Guinguené (who probably did not know, either) referred to ‘the secret of his birth’. In any case he was brought up as the child of the Nicolases. Thérèse doted on him, and he remained devoted to her until her death.

In 1745 he secured a scholarship to the Collège des Grassins in Paris. He soon distinguished himself by his brilliance and won numerous prizes. But his volatile temperament rebelled against the monotony of school life, and in 1755 he was expelled – ironically, before he could do his year studying philosophy. He fled, with a fellow pupil, to Le Havre, with a view to embarking for America. However, he calmed down and returned to the Collège, where the indulgent principal took him back. Chamfort never forgot the principal’s kindness: he grew up to be an arch-cynic with a gift for loyalty to decent human beings – when he could find them.

Fools & Lovers

The young Sébastien-Roch Nicolas was marked out for the priesthood; but his profession of faith was too lax even for mid-eighteenth century France (it was suggested that the next archbishop of Paris should at least believe in God). “I will never be a priest,” he said: “I have too much love for relaxation, philosophy, women, honour, true glory; and too little for controversy, hypocrisy, honours, and money.”

For a few years he eked out a living as a tutor and freelance writer. He was not above helping priests to write their sermons. He was also a notorious libertin, in the senses both of a freethinker and a ladies’ man. And he started to call himself ‘Nicolas Chamfort’ – or more precisely ‘de Chamfort’, asserting a claim to nobility which he could not have sustained under scrutiny.

Chamfort was less than impressed by polite society under Louis XV and Louis XVI. The words sot and sottise (‘fool’ and ‘stupidity’) recur often in his maxims as descriptions of behaviour in the high circles in which he moved. He regarded his contemporaries as slaves to the expectations of society:

“Almost all men are slaves, for the reason that the Spartans gave for the enslavement of the Persians: not knowing how to pronounce the syllable no. Knowing how to say that word and to live alone are the only two ways to preserve one’s freedom and one’s character.”

He was also annoyed by the artificiality of behaviour which characterised the age, and looked back with nostalgia to the age of Louis XIV:

“In looking over the memoirs and monuments of the age of Louis XIV, one finds, even in the bad company of those days, something lacking in today’s good company… Monsieur de Lassay, a gentle man, but with a great knowledge of society, said that you needed to swallow a toad every morning to avoid finding anything more disgusting the rest of the day, if you had to spend it in company.”

Still, he was obliged to live in that society, and to live by his wits (or wit: he could make a living by amusing them). A chapter of his Maxims is entitled ‘On the taste for retirement and dignity of character’. There he wrote, “A philosopher regards what is called a place in society as the Tartars regarded towns, that is, as a prison… The man without a place is the only free man, provided that he has a competence, or at least that he has no need of human company.” But Chamfort never had the money to retire, and in any case needed human company. He continued to write and to publish; his play La Jeune Indienne (1764) was panned by the critics, but the famous Voltaire predicted, “You will go far.”

Chamfort was often ill, largely because of a sexually transmitted disease; but in 1776 a play of his pleased the French court, and the Prince de Condé offered him a job with a pension of 2,000 livres and an apartment in the Palais Royal. Chamfort refused, preferring his independence. By now he was collecting the notes which would constitute his legacy.

In 1781 he was, on his fourth attempt, elected to the Académie Française. He later served as its Secretary. However, the most important event of his life occurred the previous year. At the salon of Madame Agasse he met Anne-Marie Buffon, the widow of a doctor, beautiful and witty, and twelve years his senior. He fell in love at once – the cynic who wrote, “Love, as it exists in society, is only the exchange of two fancies and the contact of two epidermises.” But Chamfort, on a personal level, was never as cynical as his public persona. He believed in emotion and wrote, “ Les passions font vivre l’homme, la sagesse le fait seulement durer” – “The passions make men live, wisdom only makes them endure.”

“It’s the only time in my life,” he wrote of Anne-Marie, “that I count for anything.” They set up home together near to Etampes. But there is no justice in the world: Anne-Marie died only a couple of years later, on August 28th 1783. As if that were not enough, Thérèse Croiset died the following year, aged 84. Chamfort had lost the only two women he really cared about. It may have been this double whammy which led Chamfort to violate his principles and accept the patronage of the Comte de Vaudreuil, which lasted until 1789.

Sharp Revolutionary Wit

Come the Revolution of that year, Chamfort took the side of his old friend Mirabeau, but went further. He came out as a republican and rejoiced in the decree which suppressed royal pensions (including his own). He recovered the energy which he had lost; his friend Guinguené wrote, “Throughout 1789 the Revolution was his only thought and the triumphs of the popular party his only enjoyments.”

Chamfort was not a good party man, however. He joined the Jacobin club and became its Secretary; but he maintained good relations with the opposition Girondins. He was appointed administrator of the Bibliothèque Nationale, but could not disguise his horror at the bloody reigns of Marat and Robespierre, with their enthusiasm for Mme Guillotine. Eventually he formulated two epigrams at the expense of the Jacobins: “Sois mon frère ou je te tue” (“Be my brother or I kill you”), and “They talk about the brotherhood of Eteocles and Polyneices” (the mutually murderous sons of Oedipus).

Tyrants can live with being hated, but they hate to be laughed at. Chamfort’s days were numbered. He once quipped:

“Why that phrase,” said Miss…, aged twelve, “‘learn to die?’ I see that everybody succeeds perfectly well the first time.”

Alas, not Chamfort. Anticipating arrest, on September 10th 1793 he shot himself in the head, yet survived. Then he tried to cut his throat, but he botched that as well. He lingered on, in great pain, until May 13th 1794.

After his death Guinguené published his complete works in four volumes. The fourth – the only one still in print – consisted of his notes. It was entitled Produits de la civilisation perfectionée. Products of Perfected Civilisation is divided into two parts: ‘Maxims and Thoughts’ and ‘Characters and Anecdotes’. The first contains Chamfort’s philosophical reflections and his observations on society, the second reflects his interest in the absurdities of human behaviour.

Chamfort was a great cynic; in France, in the second half of the eighteenth century, it was perhaps difficult to be anything else. But he also appreciated the quirkiness of humanity and liked a good story. The following passages reveal something of the essence of Chamfort:

“An American, seeing six Englishmen separated from their troop, had the amazing boldness to attack them, wounding two of them, disarming the others, and bringing them to general Washington. The general asked how he had come to make himself master over six men. ‘As soon as I saw them,’ he said, ‘I attacked them and surrounded them’.”

“It is well known how familiar the King of Prussia allowed some of his companions to be. General Quintus-Icilius made the most free with this. The King, before the battle of Rossbach, said to him that if he lost he would go to Venice and live by practising medicine. Quintus replied: ‘Always the killer!’”

© Martin Jenkins 2023

The late Martin Jenkins was a Quaker, a retired community worker, and a frequent contributor to Philosophy Now.