Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Fiction

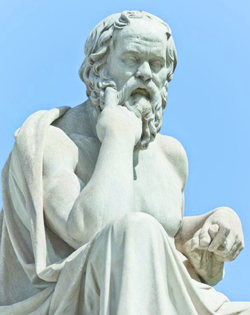

Therefore, Socrates is a Philosopher

Guy Bennett-Hunter wonders if the father of Western philosophy is a philosopher.

Professor Black: Welcome to the Philosophy Department, Mr Socrates. Please, take a seat. I’m Professor Black, Head of Department. Do you use a title?

Socrates: ‘Socrates’ is fine.

Professor Black: Very well, Socrates. It’s a pleasure to meet you – finally! I confess you’re rather taller than I expected. Anyway, regarding titles, Socrates – the V.C. and I were talking about nominating you for an honorary doctorate. So you’ll soon be ‘Doctor Socrates’, honoris causa. The question is: in which subject? Doctor of Letters? Doctor of Civil Law? Doctor of the University, even. ‘Doc Soc’ amongst the students, no doubt!

Socrates: ‘Doctor of Philosophy’, surely?

Professor Black: Heavens no, Socrates! Everyone gets a PhD – even the natural scientists! The ‘higher doctorates’ are in a different league entirely, and a D.Univ. is one of our highest honours. I’m hoping for one of those myself, when I retire…

Socrates: Tell me more about your work here.

Professor Black: As I said, I’m the Head of the Department of Philosophy. We’re small but, for our size, ranked very highly in the tables. The Department has a considerable range of expertise, and it’s non-partisan, incorporating both analytic and Continental approaches. One of my colleagues, Dr Luce, is even writing a new biography of Karl Jaspers! But I’m an analytic philosopher myself, working mainly on philosophy of mind. My epistemology is pretty staunchly externalist, I’m afraid. As Head of Department, I have considerable administrative responsibilities, but I’m very much looking forward to next year’s sabbatical, when I can get back to being a philosopher again! I’m thinking of writing a piece on Spinoza’s legacy. Of course, I realise that I might have to bring you up to speed on one or two things, Socrates. Spinoza was a monist, like many of your predecessors. Do you know we now call them the ‘pre-Socratics’?

Socrates: So this is the ‘Philosophy Department’, then, Professor Black? Or is it the ‘Department of Philosophy’?

Professor Black: The formal title is ‘Department of Philosophy’, but I don’t suppose it makes an enormous difference what name we give to our home turf. Just so long as we turn up and play the game.

Socrates: And is the Department of Philosophy made up entirely of philosophers, or are there other people in it as well?

Professor Black: Well I suppose that depends on what you mean by ‘philosopher’, Socrates! The Department employs quite a number of non-academics: the Custodian, for example; the Secretaries…

Socrates: So the Custodian and the Secretaries aren’t philosophers?

Professor Black: We call them ‘support staff’. Unlike the academics, they’re not paid to do philosophy, but to look after the building, manage student records, type letters, that sort of thing.

Socrates: I would be most grateful if you would teach me who ‘philosophers’ are, Professor Black. I infer from the little you’ve said so far that philosophers are people who are paid to do philosophy. Or have I misunderstood you?

Professor Black: I think that’s a reasonable working definition, yes: ‘a philosopher’ is a professional in the subject. Bonus points for generating grant income, though! If a philosopher’s work is financially profitable to the Department… I mean to the discipline… and helps to ensure its continued existence, then surely he is a philosopher par excellence.

Socrates: I notice that when you referred to ‘a philosopher’ just now you used the male pronoun. Surely there are today at least as many women philosophers as men? You know that Diotima and Aspasia were among my greatest teachers?

Professor Black: I’m very sorry, Socrates, that was my mistake. I really should have used inclusive language. We all need to make the effort, in small ways… The situation is considerably better than it was in your own day, true; but we still have some way to go. There are some renowned female philosophers, but the most well-known are getting on a bit now. Currently in this country, women make up twenty-four per cent of permanent academic staff – which is a considerable improvement on…

Socrates: Less than a quarter? I’m astounded that more progress has not been made in two-and-a-half millennia, Professor Black! I do hope that the situation is better among the slaves. I always found them to be very stimulating company indeed. Perhaps you’ll recall the productive conversation I had with one of Meno’s slaves? Plato frequently told me he was going to write down that conversation – although I myself do not believe in the writing-down of philosophy.

Professor Black: Thankfully there are no longer slaves, Socrates, at least, not officially. However, we do have ethnic minorities, and I confess the situation there is pretty bad for philosophy. But across the globe, universities are always implementing new policies…

Socrates: It is looking increasingly unlikely to me that we shall find our elusive philosophers solely within the universities, Professor Black. But I’m sorry, I interrupted you. You were agreeing a moment ago that philosophers are people who are paid to do philosophy?

Professor Black: Yes, and if they can generate some grant income, so much the better. There’s also increasing pressure on us to demonstrate the ‘impact’ of our research – to show a measurable influence on the world beyond the university.

Socrates: It’s possible today for a person to do philosophy outside a university?

Professor Black: Yes, of course – just as it was in your own time – though it wouldn’t be very easy to make a living like that today. But I’d love to see your ‘impact’ rating, Socrates: it would probably break the Research Excellence Framework!

Socrates: As I say, any credit for any impact I’ve made would be due to my brilliant students alone, Professor. But, tell me, are there any unpaid philosophers in the university?

Professor Black: I see where you’re going with that one, Socrates… But there’s always the exception that proves the rule. In addition to our permanent academic staff, we have stipendiary and non-stipendiary postdoctoral researchers, honorary research staff, full- and part-time teaching fellows on temporary contracts, and hourly-paid teaching assistants.

Socrates: And are all of those people philosophers, or only some of them?

Professor Black: All of them, of course. They’re all members of the Department of Philosophy.

Socrates: Come now, Professor Black, I thought we had already agreed that the Department of Philosophy is made up of both philosophers and non-philosophers. Or have you forgotten?

Professor Black: Of course we did, I’m sorry.

Socrates: But I gather that some of the philosophers you just mentioned are paid for only part of their time, and others are not paid at all. Is that correct?

Professor Black: Yes, that’s correct; but in the current climate we simply don’t have the funds to…

Socrates: And what about philosophers outside the university? For instance, a short while ago, you mentioned a philosopher called ‘Spinoza’ about whom you’re planning to write. Was he paid to do philosophy?

Professor Black: As a matter of fact, your supposition is correct. Spinoza was not attached to a university. He was a lens-grinder by trade. But he lived a few centuries ago, and made important contributions to the optics of his day.

Socrates: Professor Black: it seems that philosophers aren’t people who are paid to do philosophy after all. If past philosophers who are studied here in the Department of Philosophy weren’t paid to do philosophy, and there are also philosophers working in this Department who aren’t paid to do philosophy, do you think we can really accept that definition?

Professor Black: I see the difficulty, Socrates. I don’t think we can accept it, after all.

Socrates: Perhaps you’ll also recall that I never accepted any payment for my endeavours. But then, perhaps I’m not a philosopher.

Professor Black: Come now, Socrates! If anyone’s a philosopher, you are. We just need to do a bit more work on our necessary and sufficient conditions for what makes someone a philosopher.

Socrates: I must say I’m finding our little discussion most enjoyable, Professor. But I would find it even more stimulating if you would teach me who these special paid philosophers are that you mentioned when we started talking?

Professor Black: Well, I was referring to professional philosophers like myself. I’m paid a salary by the University; I have a permanent contract; and I’ve generated a small amount of grant income as time has permitted. I’ve published my research in top peer-reviewed journals – plus a few monographs. Perhaps we can say that these days, a philosopher is someone who has published at least one peer-reviewed work of philosophy – though most departments would struggle to justify a new appointment if he… I mean they … had only one publication.

Socrates: Tell me more about this. What does a ‘peer review’ involve?

Professor Black: Well, when a professional philosopher submits a manuscript to a journal or a book publisher, the editor sends it to two or three other philosophers, who assess the academic quality and make a recommendation as to whether or not it should be published.

Socrates: And do you think that this will help us to find out who philosophers are?

Professor Black: Yes: as I say, a philosopher is a man or woman who has published one or more peer-reviewed works of philosophy. In other words, a philosopher is someone whose work has been judged important by other philosophers.

Socrates: Can you not detect a difficulty here, Professor Black? If we don’t yet know who philosophers are, how do we know whether the people judging their work are themselves philosophers, let alone the people whose work is being judged? Are we not defining philosophers in terms of themselves?

Professor Black: Yes, I see the circularity.

Socrates: And you still haven’t taught me who philosophers are. But perhaps I’m getting too distracted by this ‘peer review’?

Professor Black: Yes, very likely. By philosophical standards, it’s a very recent invention. Historically, what’s more important than peer review, is the writing and publishing of philosophical works.

Socrates: So philosophers are people who have written and published works of philosophy?

Professor Black: Don’t say it, Socrates…

Socrates: You’re ahead of me, Professor Black! But allow me to refer you to a work by one of my ‘doctoral students’, as you might call him.

Professor Black: You mean the Phaedrus, where Plato records your suspicion of writing? I recall that Plato has you say there that, unlike a living person, a text can’t reply to its reader, answer objections, or defend itself. And also that writing might enfeeble the muscles of memory.

Socrates: Quite right. Your own memory clearly hasn’t been enfeebled. Although Plato did not write down my exact words on that subject. Perhaps he misremembered them.

Professor Black: Perhaps we should instead then say that philosophy can only be done in dialogue, which may or may not be written down and published? But indeed, I can’t think of any philosophy journal that would publish a dialogue these days.

Socrates: So even if we put my misgivings about writing to one side for the moment, if philosophy is dialogue about philosophical topics, it can’t be necessary for philosophers to have published anything in order to count as philosophers, can it, if they can’t get that dialogue published?

Professor Black: I suppose it can’t.

Socrates: It seems then that the philosophers have escaped us once again, Professor Black! But I’m encouraged by the progress we are making. We seem to have discovered some of the things that definitely do not make people philosophers. Being paid to do philosophy doesn’t make people philosophers; nor is it necessary for philosophers to have published anything. Perhaps, indeed, they need never have written anything, either.

Professor Black: Perhaps.

Socrates: You regard yourself to be a philosopher, do you not, Professor Black?

Professor Black: Of course I do.

Socrates: Do you think then that self-identification as a philosopher could be enough?

Professor Black: : Certainly not! For a start, there are many renowned philosophers who rejected the label. Hannah Arendt was without doubt one of the leading philosophers of the twentieth century – another philosopher who would have had a superb ‘impact’ rating – though I’m not sure how she would score on ‘student satisfaction’… Anyway, she had a PhD in Philosophy, but said in a late interview that she felt rejected by the philosophical community, and so explicitly rejected the label ‘philosopher’ for herself.

Socrates: I think she and I would have got on well.

Professor Black: Besides, Socrates, all sorts of people could call themselves philosophers, but without having gone through any kind of formal training.

Socrates: Does this apparent requirement for formal training bring us any closer to an understanding of who philosophers are?

Professor Black: Yes, Socrates, I believe it does: a philosopher is a person who has been formally trained in philosophy. Today, long after Plato’s invention of the academy, that would imply a PhD, or at least, a degree.

Socrates: And that’s what allows you to call yourself a philosopher?

Professor Black: Yes, Socrates, I believe it does.

Socrates: I understand, Professor Black, that you’re not keen on the idea that just anyone could be a philosopher. You want to be sure that they have undergone the necessary training, just as you yourself have. But perhaps you can clarify something for me. Earlier I was introduced to one of your colleagues in the Department of Psychiatry – Professor Tamworth. Interestingly enough, he mentioned the same philosopher, Karl Jaspers, whom you spoke of earlier. He was telling me that before Jaspers became a philosopher, he wrote an important book on the classification of diseases of the mind which formed the basis of the diagnostic manual that’s still used in psychiatry. So I asked him whether Jaspers was a psychiatrist. Professor Tamworth replied rather forcefully that Jaspers was not a psychiatrist. He told me – with a rather triumphant look, it has to be said – that although he qualified as a doctor, Jaspers never held a training post in psychiatry, and was therefore not a psychiatrist. It seems that the ‘impact factor’ counts for less in psychiatry than it does here in philosophy! But if Jaspers was trained as a philosopher and got his PhD in that subject, then I believe we have discovered his true identity. We may indeed be closer to finding out who philosophers are.

Professor Black: As a matter of fact, Socrates, Dr Luce told me that Jaspers didn’t have a degree in philosophy – only in medicine.

Socrates: But did you not say a short while ago that philosophers are people who have been formally trained in philosophy?

Professor Black: I did.

Socrates: How extraordinary, Professor Black! Do you mean to say that Jaspers had such a huge influence on both psychiatry and philosophy that his work is still studied by psychiatrists and also philosophers in this very Department – yet he himself was neither a psychiatrist or a philosopher?

Professor Black: I can’t speak for psychiatry.

Socrates: But as a professional philosopher, you surely won’t demur from voicing your professional opinion on that aspect?

Professor Black: I have nothing to say, Socrates. You’ve bewildered me.

Socrates: You know, Professor Black, you remind me of my old friend, Crito, who shared your talent for falling silent just when the conversation was getting interesting! But I will not give up before you teach me who philosophers are. In fact, we’ve been talking for almost half an hour, and I think we’ve made some real progress. It seems most likely to me that some philosophy has being going on; if not here in this room, then at least somewhere in the Department… But I am beginning to wonder whether our search has gone awry, for it has led us to individuals, while philosophy, as we said, is done in dialogue. Perhaps it is only when two or three philosophers are gathered together that Athena is among us.

Professor Black: It’s the first week of the Michaelmas Term, Socrates. She is most certainly with us today.

Socrates: Then there must be some philosophers somewhere nearby – if only we could find them!

Professor Black: I’m afraid we shall have to look for them some other time, Socrates, or we will be late for your lunch with the Vice-Chancellor; and I know that you have other departments to visit. You will have a cup of something before you go?

Socrates: I’m sorry that our conversation has come to such an abrupt and final ending, Professor. I had not expected that I would have to drink my last drink a second time. I think this one really will be the death of me. Shall we pour a libation, Professor Black?

© Guy Bennett-Hunter 2023

Guy Bennett-Hunter is Executive Editor of The Expository Times at the University of Edinburgh, and a mental health professional.