Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Everything, All the Time, Everywhere by Stuart Jeffries

David McKay enjoys Stuart Jeffries’ lively take on postmodernism.

Another book on post modernism? Isn’t that yesterday’s news? Or maybe last decade’s? Surely postmodernism has been analysed virtually to death; and hasn’t contemporary thought moved on, anyway?

To some degree that may be true: the label ‘postmodern’ is perhaps not attached to ideas and practices as frequently as it was a few years ago, and the number of studies explicitly dealing with postmodernism has declined. That, however, doesn’t mean that postmodernism has gone away. The historical pattern for idea development, is often that a set of ideas bursts onto the intellectual scene and becomes the dominant talking point for a time, until some of its principles are absorbed into the perceived wisdom of the day, part of the accepted way of thinking, whilst their origins are gradually forgotten. Given that postmodernism was a diverse movement rather than a unified philosophy, such piecemeal absorption was all the easier. So what’s postmodern in our culture now?

But first, what is postmodernism (or as Stuart Jeffries prefers it, ‘post-modernism’)? Even a fairly modest acquaintance with postmodern practices shows that it’s difficult to come up with a single definition that covers the whole field.

Jeffries offers several possible approaches. The first sees close connections between developments in many cultural settings of the movement that became known as postmodernism and the growth of neoliberalism, in the days of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. According to this model, in Jeffries’ words, neoliberalism, with its focus on free trade, free markets, and private property rights, needed “a populist, market-based culture of differentiated consumerism and individual libertarianism” (p.3). Postmodernism fitted the bill, and so, to a significant degree, neoliberalism co-opted postmodernism for its consumerist ends.

Or maybe not. A contrary second model argues that postmodernism is “the story of an idea as liberation from the constraints of the modern world that dehumanised us, reducing us to cogs in modernist machines” (p.7). Against the rigid industrialism of modernism, postmodernism offered freedom, utopia, an anything-goes society. Critics, however, suggest that modernism was not nearly as oppressive as it is portrayed by postmodernists, and indeed that modernism and postmodernism simply offer two different methods of social control. One tyranny had been swapped for another.

Jeffries also considers further suggestions, such as Wittgenstein’s idea of ‘family resemblances’ between apparently diverse phenomena; but he finds such diversity that the search for resemblances fails. Another possibility Deleuze and Guattari suggested, draws on the concept of a ‘rhizome’, meaning, a complex of interconnections without beginning or end. If, however, the diverse facets of postmodernism have no common ancestors, no ‘family tree’, Jeffries suggests that they can, in fact, simply stand alone.

He offers one more possibility: postmodernism is “a semiotic black hole, consuming everything but signifying nothing” (p.17). He continues, “How post-modern thought might express its critique of signification from inside that black hole is an interesting question for students, though one they would have trouble communicating to the outside world.”

Then, rather than an attempt at a comprehensive history of the movement, the book is a selection of ‘moments’ from 1972 to 2001 that exemplify the diversity of postmodernism, gathered into ten chapters, each with a focus on a particular year. Jeffries chooses 1972, 1975, 1979, 1981, 1983, 1986, 1989, 1992, 1997 and 2001. For each year he selects three significant items – it could be people, events, places, or cultural products such as a film or another artwork – which exemplify the postmodern impact on trends evident that year. Readers will encounter, for example, Ziggy Stardust, Margaret Thatcher, the Apple Macintosh, the Musée d’Orsay, the Rushdie fatwa, Silicon Valley, Netflix, Grand Theft Auto, 9/11, and debt. The range indicates the breadth of postmodernism’s reach into many diverse areas of culture.

We can get a flavour of Jeffries’ approach by taking a specific example. Chapter 6, ‘The Great Acceptance, 1986’, considers Rabbit, Quentin Tarantino, and the Musée d’Orsay. (1986 was chosen for Jeffries’ evaluation of Tarantino because that was the year in which Tarantino got his first job in Hollywood.)

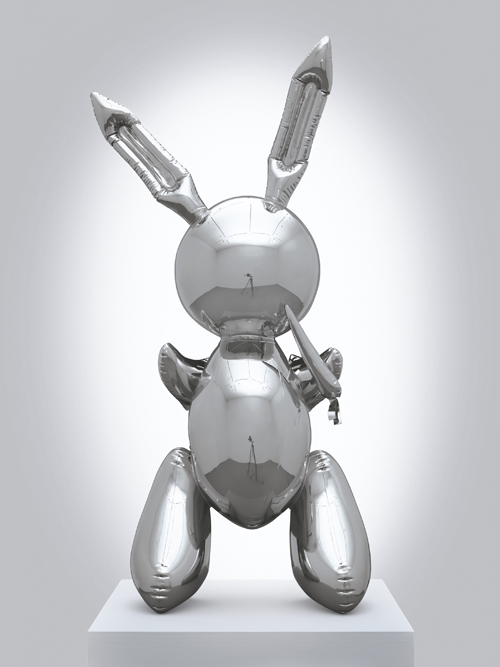

Rabbit, produced by the world’s most profitable living artist, the American Jeff Koons, is a forty-one-inch-tall stainless steel casting of an inflatable rabbit holding a stainless steel carrot. It was first exhibited at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York in autumn 1986. On the one hand, Jeffries argues, the sculpture is “dense with semiotic significance” (p.179) – meaning that it’s an artwork in which one can ‘see’ a multitude of images, from Neil Armstrong’s lunar helmet to Bugs Bunny. Nevertheless, Jeffries also argues, Rabbit is in fact empty. As he puts it, “It is post-modern in favouring style over substance and surface over depth, forcing high art and low culture into profane embrace”. In Jeffries’ view, Rabbit also “prefigures the age of the selfie, in which we only look in order to see ourselves” and the work “alternates from sublime to ridiculous, from rococo pastiche to cartoon bunny; sublime but ridiculous; sublime and then ridiculous.”

Rabbit by Jeff Koons. A snip at only $91.1 million. (It’s the world’s most expensive sculpture!)

Jeffries goes on to consider the wider context of Rabbit, namely the contemporary art market, arguing that in postmodern culture the value of art is financial rather than aesthetic. Artworks have become commodities, and artists such as Koons have generated large fortunes for themselves by producing work that appeals to millionaire collectors just because of their collectability, rather than their aesthetic appeal. This Jeffries contrasts with the perspective of the neo-Marxist modernists of the Frankfurt School, where the philosophers (such as Herbert Marcuse) believed that art had to serve a politically disruptive role in order to be of value. Koons’ vision of art, according to Jeffries, puts all art-forms – “high and low, art and porn, even good and bad” – on the same level, offering no critique of society, and especially abandoning any idea of changing it for the better. Koons, says Jeffries, encourages us “to accept a neoliberal order in which art becomes indistinguishable from narcissism and pornography” (p.186). In the end we become inured to Koons’ ‘shining fatuity’.

Jeffries sees in Quentin Tarantino’s films the same kind of ambiguity he believes is present in Koons’ art. He sums up the problem in this way: “His too is an art that flatters his audience, bewitching them with intertextual references to other films and pop culture, thereby deflecting thought and encouraging acceptance of the self and the status quo” (p.186). In true postmodern style, Tarantino draws on all kinds of cultural sources that will be recognised by his audience; but, Jeffries contends, his goal is that “we are able to anaesthetise ourselves to the venal things that happen in the film” (p.191).

Although some critics have accused Tarantino of moral vacuity, Jeffries argues instead that Tarantino’s moral interest consists in a deliberate lack of moral interest. He claims that nevertheless, behind the diversity of sources, Pulp Fiction has a moral message: “the influence of globalised capitalism overrun by neoliberal ideas.” Here is the same unholy alliance that Jeffries has noted in so many areas of postmodernism. The central characters in Pulp Fiction are consistently portrayed as consumers: in the film, “buying, consuming and owning have become dominating, self-justifying ideals, while the film’s murders, racism and homophobia go unchallenged” (p.192). And “thanks to the internet, post-modernism can stupefy us more efficiently than before” (p.193), with what Jeffries perceives to be its neoliberal consumerist worldview.

And so to the Musée d’Orsay, a Paris art gallery which opened in 1986. This converted railway station was one of the building projects that transformed Paris during the presidency of François Mitterand from 1982 onwards. Jeffries’ evaluation of the philosophy shaping the gallery’s displays and activities (not least the gift shop) is profoundly critical of the baneful influence of what he terms the ‘culture industry’ imported from Hollywood. It is culture through shopping. Indeed, you could shop online and avoid any experience of the gallery’s art. Jeffries really doesn’t like the Musée d’Orsay, with what he perceives to be its neoliberal focus on consumption at the expense of art, and indeed, everything else.

Central to Jeffries’ evaluation of postmodernism is the link he discerns between postmodern values and the neoliberal economic system which nurtures and promotes them. To critique that neoliberalism, he makes frequent reference to Critical Theory, the post-Marxist theory associated with the Frankfurt School of thinkers such as Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, which aims to liberate people from whatever is perceived to enslave them. Although others have regarded Critical Theory as a promoter of postmodernism, Jeffries argues from the opposite point of view.

Whilst many believe that postmodernism is dead, or dying, Jeffries argues that this is a misunderstanding. For him, “Its spirit still thrives, and it shows no sign of rolling over. It lives among us, expressed in post-truth politics, gender theory, the overturning of high art’s values. Digital technology and social media have hardly made post-modernism obsolete; rather, they have given it new life” (p.329). In a concluding meditation on the postmodern influence on architecture in his part of London, he concludes, “We need in our culture, not more irony and wit, but more thoughtfulness and kindness. I’m not at all sure that the values of post-modern architecture have much to do with those virtues, but here in a little corner of London, they thrive despite the cruelty and rapaciousness of neoliberalism all around” (p.335).

Everything, All the Time, Everywhere is no dry, neutral exposition of philosophical theory, but a lively, engaged, critical tour of a wide range of postmodern phenomena. It gives us plenty to ponder, plenty to debate. So perhaps postmodernism is not such old news after all.

© David McKay 2024

David McKay is Professor of Systematic Theology, Ethics and Apologetics, at the Reformed Theological College, Belfast.

• Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern, by Stuart Jeffries, Verso, 2021, 384 pages, £11.99, pbk., ISBN 978-1-78873-822-4