Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Love Lies Bleeding

J.R. Dickerson decodes a film that likes to pretend it doesn’t have messages because it’s a comedy.

Katy O’Brian got ripped [muscular] for her role in Rose Glass’s second feature, the 2024 lesbian romantic comedy Love Lies Bleeding. Her character, Jackie, is a doe-eyed drifter who, sometime in the 1980’s, rolls into the small New Mexico town where Lou (Kristen Stewart) works at a gym so gritty, sweaty, and testosterone-drenched that it makes Rocky Balboa’s boxing club look like a five-star resort. After banging Lou’s cheating, wife-beating brother-in-law JJ in the back of his car, Jackie sleeps under a bridge and wakes up the next morning ready to pump some iron to prepare for an imminent Las Vegas bodybuilding competition. Viewers are left in no doubt as to her prospects. You see, Jackie codes as male in all but phallus, and her rippling muscles are given a staggeringly unnecessary boost by the steroids she regularly injects after tossing her ‘ au natural, baby’ policy aside following a single flirtatious nudge from Lou. In about five seconds flat the two women are doing the horizontal tango. After about a week, in true lesbian style, they declare their love for one another and will betray family to prove it if necessary.

The director and co-writer, Glass, defies genre and narrative, and indeed any commitment to any point, by making the film such a parody of itself that it’s like a movie-length exercise in plausible deniability. Any message it may have sent about gender, feminism, or anything else, is done with so much hyperbole that it becomes a joke. This makes it little more than a parade of images and ideas unconnected to any statement. And yet it’s packed with infotainment that works on the subconscious like hypnosis, partly by means of the ‘mere exposure effect’ – a propaganda trick in which just being exposed to a concept or image softens the subject, allowing him to normalise what he’s exposed to. There’s also a man-sized helping of ‘associative conditioning’: a technique that links something you already like or value with something more controversial, so that the appealing connotations of the former will rub off on the associated object or concept. (It also works negatively, by the way – by associating an idea with things you hate or despise.)

Now I’m probably just too old-fashioned, but the way the film doesn’t take anything seriously is frustrating because it renders it impossible for me to get my hooks into a critique of its transgender and transhumanist subtextual propaganda. One could, for example, easily be fooled into thinking that this is a feminist film. For instance, Jackie lays some seriously brutal payback on wife-beating philanderer JJ. But true to its self-parody, all the men in the film are caricatures: they’re either scumbags, like JJ and Lou Sr, or just stock characters, like the FBI agent. Ed Harris plays Lou’s bug-munching, gun-toting Dad, and looks not unlike Richard O’Brien in The Rocky Horror Picture Show thanks to his hideous hairstyle. There are plenty of refreshingly ‘unfeminine’ forms of womanhood represented in the film. And yet the gender non-conformity and ostensible feminism are illusory. In their place are a set of subtextual messages, including:

1) Truly cool lesbians get turned on by, and have sex with, male-bodied people;

2) Injecting steroids is a fun and easy way for boyish lesbians to stay hard;

3) Injecting pharmaceuticals is sexy and provides an unproblematic way of changing your body to make it fit the image you want;

4) Guns are for insecure men, and only misogynist reprobates use or sell them;

5) Feminine cisgendered lesbians are clingy and cringe-worthy; not to mention that they have unappealingly soft, ‘fat’ bodies;

6) Straight cis women are hopelessly stupid and weak, and possibly deserve the abuse they get from cisgendered men;

7) Bugs are food and, while that seems gross, it doesn’t hurt to get the idea of eating bugs into your mind; and

8) Straight white men are misogynistic trash.

None of these ideas are explicitly expressed, though, and I will no doubt be raked over the coals for misinterpreting the film. But my point is that there is no way to correctly interpret it, because if you try you’ll be told you’re taking it too seriously. However, I didn’t take the film seriously at all; so I’m on board with the whole ‘Hey, the film isn’t making a statement’ disclaimer. It isn’t. And yet, it is. Which is why I’m allowing myself to unpack the non-meanings that just aren’t there, but are. It’s kind of like eating those jellybeans that taste like coconut, vanilla, or pineapple, but are just a jellybean so you can’t blame them if they have zero to do with real coconut, vanilla, or pineapple. Similarly, you can’t critique Love Lies Bleeding as though it takes itself seriously. And yet, for our susceptible brains, a very cool-looking, attractive lesbian like Lou, some dazzling images of muscles, and a decent soundtrack, are associated with ideas 1-8 above. So while the movie is not straightforwardly trying to normalise the idea that lesbians are attracted to the male anatomy, or that chemical injections are a fun and easy way to change our bodies, or even that insects are food, associative conditioning is employed to get us to regard its ideas as ‘cool’, so that anyone reluctant to buy into them is uncool, and probably ‘right wing’. So, go and enjoy this fun movie, and maybe be titillated by the gratuitous and overly long lesbian sex scenes – but don’t walk away thinking that nobody’s messing with your mind.

Movie image © A24 2024

Perhaps I’ll be told that I’m unaware of my own bigotry against butch lesbians (even though I am one): after all, Jackie is doing some radical and progressive stuff by bending female gender norms. She’s stronger and larger than most of the men in the film; she is the beefiest hunk in the mostly male gym; she has sex with women; and she can’t be kept in a kitchen to (literally) save her life. And yes, there are women bodybuilders in the real world who have bigger muscles than most men, and who sleep with women, and who are tough. Hooray for them! However, there’s only one type of ‘woman’ who could realistically do all the things that Jackie does in the movie (including beat up men, tower over them, and fearlessly hitchhike with male drivers) – and we all know which ‘women’ I’m talking about. To make matters worse, Jackie shoots Lou’s annoying cis femme paramour in the back of the head, and when she drops to the floor, we’re instantly given the sight of square-jawed brawny Jackie holding the gun while at the same time looking as though she’s the vulnerable victim. (Is this ringing any bells?) Unfortunately for Jackie and Lou, the female-bodied lesbian wannabe girlfriend isn’t that easy to get rid of, and is still breathing. Butch Lou realises what must be done and finishes the job. So much for the sisterhood.

All this subtext might explain why the film so often lurches into unrealistic fantasy – because it isn’t going to say anything direct about its underlying ideology and so open itself up to either a feminist or a lesbian critique. So here’s my lesbian non-critique of a film that hasn’t got the guts to be honest about the messages it purveys because if it dared, lots of people would hate it. As it is, just enjoy the spellbinding flow of images and associations that lead you ever deeper into transgender ideology.

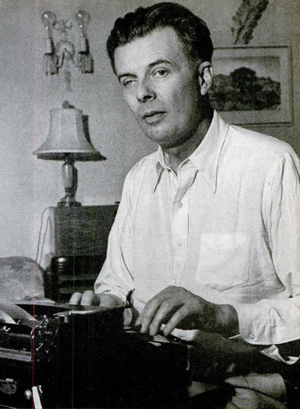

Aldous Huxley in 1947

anonymous Public Domain

In Brave New World (1932), Aldous Huxley pictured a future of captivity through anodyne entertainment, sexual ‘liberation’, and drugs. In his later collection of reflective essays, Brave New World Revisited (1958), Huxley discussed methods of mass persuasion, including associative conditioning. The most subtle and insidious form of propaganda appeals not to reason, but to the emotions, passions, and prejudices that lie beneath the surface of consciousness. The principles underlying the technique are, he says, simple. First, find a widespread unconscious fear or anxiety. Second, find a way to relate this fear to the product or idea you wish to sell. Finally, build a bridge of verbal or pictorial symbols over which the subject can pass from his fears to the dream – by using the product you’re selling as a ‘solution’. At times, says Huxley, the symbols take effect by “appealing only to the aesthetic sense” and not to “the truth nor the ethical value of the doctrines with which they’ve been… associated.”

In Chapter 9, ‘Subconscious Persuasion’, Huxley describes one of the most effective methods of non-rational persuasion, which he calls ‘persuasion-by-association’. This involves the propagandist associating his chosen product, candidate, or cause with some idea that most people in the culture he’s addressing unquestioningly regard as good. Huxley recounts an example from Guatemala that awed him when he witnessed it. American calendars published by an aspirin manufacturer failed to sell the pain-relievers among Guatemalans. However, German advertisements for aspirin were very successful with the same audience. The difference was that the German advertisers had taken the time to find out what Guatemalans valued and were interested in. The American calendars had adverts that associated the pills with depictions of American values and lifestyles, while the Germans associated the pain-relief tablets with the Holy Trinity, St Joseph, and the Virgin Mary.

I’m afraid that Love Lies Bleeding works in a similar way; and yet what it’s selling is not some item that can be bought cheaply in small quantities, but something larger and more abstract, which will cost us something dear. The clue to the ideological ‘product’ that the movie’s selling may be found in the second word of the movie’s title.

Often, what subconsciously influences us hides in plain sight. Seeing it is a matter of putting on the decoding glasses, and so perceiving the symbols and meanings that are right in front of us.

© J.R. Dickerson 2024

J.R. Dickerson is a gender non-conforming liberal feminist autodidact. She loves movies with strong female leads, slam poetry, fiction that does not masquerade as fact, and equine therapy.