Your complimentary articles

You’ve read three of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Fiction

Cave Girl Principles

Larry Chan takes us back to the dawn of thought.

Stick was curled on a rock jutting out of the ice sheet. Her long red hair was tangled around her small flinted spear. Her bow rested at her side, along with its one remaining arrow. She furrowed her brow at the oxen in the distance. Many thoughts were on her mind – but one thing she could not have fathomed was that autism existed even in the Ice Age. Neither did she know that creative geniuses emerged from the gene pool long before the glaciers took the planet. Stick also knew nothing of the Neanderthals that had roamed the lands ten thousand years before her birth.

She’d already expended about a third of her expected lifespan: she was celebrating her seventh birthday. It was curious that she knew it was her seventh birthday, for not even her elders yet understood the concept of number, or that the stars followed a precise yearly pattern. But Stick knew much more than basic integers. She understood the concept of acceleration. She knew that falling objects moved at the same speed. She also knew that firing an arrow at a 45-degree angle maximized its travel distance. She was just waiting for the prey to come into range.

Eventually, a young calf wandered the wrong way. Her stone-tipped wooden missile flew in a parabolic trajectory and became lodged in its neck – at a 45-degree angle. Once its herd had abandoned it for dead, Stick tied a rope around its hooves and dragged it across the snow.

Once the stars showed themselves, she lit herself a campfire and created a fence of wooden stakes in a circle around her, sharpened ends pointing outward. She knew the fire would attract wolves; but she hoped it would also attract her tribe, from whom she had been separated during the last hunt.

She burnt her dinner to a crisp. She liked the way the charcoaled skin of the ox leg bubbled with fat. Then she gave herself a snow bath.

The night sky was the best show around – indeed, it was the only show around. Most people only saw the constellations as representing celestial beings, the most notable being the three stars that were perfectly aligned like the belt of a hunter. Stick was looking in that direction when she saw something else entirely, in her mind: it dawned on her that the force that made things fall was a warping of the very fabric of the world. She imagined it as a mammoth hide that was stretched out, with a big stone placed in the middle. Smaller stones would rotate around the big stone because the fabric was forcing them to, not because the central stone was making any direct contact with the other stones.

The world she was standing on was not the center of the universe. She had already figured that out long ago. But she wanted to delve deeper. She had found two natural rock crystal beads that were clear and curved. Aligning them one in front of the other and adjusting the distance between them, she had been able to see, instead of just the twinkling light from one of the Wanderers, a pale little orange disk with four tiny sparks adjacent, all in a line. She had looked at that Wanderer through her two beads on many clear cold nights. Sometimes the tiny sparks were all on the same side of the disk, sometimes two on each side, sometimes she could only see three of them… They were like little wolf cubs circling their mother. Then that reminded her of the big bright Moon coming up over the hills. Maybe the little wolf cubs are little moons, she thought. Her father had said the Wanderers were the souls of lost hunters. It wasn’t a soul. It was another world, perhaps like the one she was sitting on.

Ironically, at midnight a pack of circling wolves surrounded her. Stick remained at ease. It wasn’t because she was brave, for she knew that she was not: it was because the stakes she had arranged were angled higher than the wolves could jump, and buried too deep for them to ram down into the snow. A younger wolf tried to leap the fence, resulting in a bloody side. They also tried to shove the shafts aside, as if their pride was at stake. The girl took up a bare ox bone she had topped with tar, dipped it into the fire, and poked the blazing torch at them between the spears. They gave up in search of an easier meal. Wolves had limited pride compared to their urgent survival needs on the cruel glacier.

She knew how puppies were born, and suspected humans did something similar. Though she couldn’t prove it, she guessed this was how all the animals came to be. She also noticed that children looked like their parents, and that the weaker children died more quickly. Weaker individuals died, but the stronger or faster ones grew and had children who were often strong and fast like themselves. There was no magic, no higher powers, just dumb chance. She might have rolled a knucklebone dice and had the same chance of creating a world.

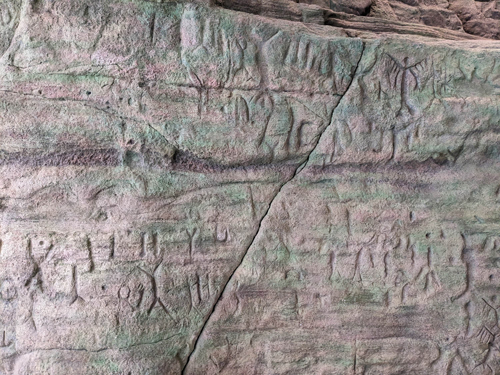

cave wall etchings © Zaddikskysong 2023 Creative Commons 4

A present example of such dumb luck was provided by the cave lion that skulked up to inspect her miniature fortress, for it had the strength to plow down her wooden stakes, if it avoided the tips. Stick had been hoping that the lions were asleep for the winter. Her mother had impressed upon her the importance of learning the animals’ habits, but Stick hadn’t listened. She had no regrets if she was going to be eaten – although she was sure she would change her mind once her head was between the lion’s jaws. But her luck held. She splashed the puddle of hot ox fat that had formed at the base of the fire at the lion’s face. She poked at it with her greasy bone torch. Its fur was set alight. It ran off and rubbed itself in the snow. Then a passing ibex proved easier to chase down, so the lion left her in peace. She roasted another ox leg, making sure to retain multiple fat puddles.

The light of the campfire caused her shadow to flicker. She wondered if light flowed like a stream of water. Contemplating the question, she concluded that light had a speed that could neither be reduced nor increased. But if the speed did not change, what would happen if she launched an arrow at the same speed? If the arrow perceived the light moving at the same speed, this would mean the arrow would be frozen in time for as long as it was racing like a light beam. Time itself would change! And if the river were light, and she ran at its flow, she would appear as unchanging as a rock to someone looking from the outside.

She imagined running alongside a river. If she ran fast enough, the river would appear to move backwards!

She wondered why the world was so strange. Was light and the other things keeping secrets? But they couldn’t lie, those strange concepts in her imagination.

When her family found her at dawn, she tried to tell them all the new things she’d discovered while alone under the stars. As was traditional by now, her parents ignored her. The other elders had long dismissed her talk as childlike babble. The other children ignored her too, and went off to practice spear throwing. They hadn’t an inkling that beneath her skull an abnormal amount of energy was being devoted to abstract reasoning; they merely noticed the effects of this resource-diversion.

Stick had difficulty making eye contact. Her way of talking was unnerving, and she was considered to be weird. So despite being a physically healthy, attractive child, she was relegated to the position of the weakest member of the tribe. Stick just wanted to tell her tribe that there was more to life than hunting and foraging: that the cosmos would continue spinning planets and stars, and emitting light beams that altered time itself, for long after they embraced the death that was so imminent for all of them.

A few weeks later, Stick began thinking about how small things worked. She got as far as concluding that the smallest bits of stone were probably made of little fragments of rope that held even smaller stones together – but there was little in their language that could express her concepts. So she took to drawing on every stone wall she could find, in an attempt to etch pictures of what was on her mind, in the hopes that future generations of hunters perhaps would understand. Still, the boys of her tribe found spear technique more interesting, and the girls would not talk to her at all.

Millennia later, paleontologists discovered her etchings and paintings on a cave wall. They concluded it was decorative art.

© Larry Chan 2024

Larry Chan is a screenwriter and actor. He was a semifinalist in the 2019 PAGE International Screenwriting Awards for his feature-length screenplay The Black Knight’s Squire. He wrote and directed the short films Wereshark: Neptunerise and Reinek: Marslight, which are now on his YouTube channel.