Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Tallis in Wonderland

A Lifelong Preoccupation

Raymond Tallis recalls a life trying to fathom the chasm between mind and brain.

I have been preoccupied with the relationship between the mind and the brain for six decades. I remember arguing with my infinitely patient Oxford neurophysiology tutor in the 60s about whether or not vision really did boil down to activity in the occipital cortex. In the 70s, I read endless articles about the ‘mind-brain identity theory’, wrestling with the notion that conscious experience could be reduced to the passage of ions through semi-permeable membranes.

In the 80s the idea of the brain as a biological computer and what went on in it as ‘information processing’, became increasingly popular. According to many scientists and philosophers, information was everywhere, so the gap between brain and mind could be crossed without the need for an explanation of how nerve impulses were promoted to mental contents. I suspected this was a fudge, and so in the 90s I published a ‘lexicon of neuromythology’ (Why the Mind is Not a Computer: A Pocket Lexicon of Neuromythology, 2004), arguing that the idea of the brain-as-computer was based on terms that applied only to conscious human subjects, and not, say, to actual computers.

At about this time, some philosophers who believed that the mind was largely anchored in, or generated by, the brain, argued that the body as a whole also had a role in consciousness. The mind was ‘embodied’ rather than merely ‘embrained’. This didn’t help much because it was never clear how much of the body was involved, given that what happened in circulatory systems, muscles, and a smorgasbord of giblets under the skin did not seem particularly ‘cognitive’ in nature. And the invocation of technological aids as being part of the so-called ‘extended mind’ cast little additional light on the fundamental problem of how objectively observed physical events could account for the fact that Raymond Tallis, and, so far as he could tell, his fellow humans, were aware of themselves and of the world in which they passed their lives.

By the 2000s I was sufficiently settled on rejecting the mind-brain identity theory that I started using the term ‘neuromania’ to designate a widespread tendency to invoke neural activity to try to explain every aspect of consciousness, from the experience of itches, to the creation and appreciation of works of art, and the adoption of religious beliefs.

That should have been the end of the story, but it was not. After all, there were, as my Oxford tutor had reminded me, compelling reasons for thinking that the brain has a particularly close relationship to every aspect of consciousness. Beyond the headline fact that being beheaded rather reduces one’s IQ, there are close correlations between more localised brain damage and more specific impairments of consciousness and cognitive function. My day (and night!) job as a doctor, treating patients with conditions such as stroke, epilepsy, and Alzheimer’s dementia, was a constant reminder of this. Intactness of the brain seemed, at the very least, a necessary condition for the everyday consciousness of everyday life. But did it mean that it was a sufficient condition, or even that what went on in my brain, or parts of it, was identical with what went on in my mind?

In recent decades, ever more sophisticated ways of studying the brain in waking subjects – for example functional magnetic resonance imaging and brain stimulation using intracerebral electrodes – have revealed often very close correlations between conscious experience and neural activity. It is, or should be, difficult for neurosceptics like Tallis to ignore reports such as that of a brain-computer interface that decodes impulses for handwriting movements in the neural activity in the motor cortex in a paralyzed patient unable to use his hands, and translates this into text in real time (‘High-performance brain-to-text communication via handwriting’, Francis Willett et al, Nature 593, 2021).

Nevertheless, this does not alter the fact that consciousness is, or seems, fundamentally different from brain activity. There is the intentionality – or aboutness – of conscious contents. That light reflected from an object causes activity in my visual cortex seems relatively straightforward; but it is not at all clear how this results in my seeing the object. We can understand how the light gets in and tickles up the neurones but not how the tickled-up neurones become a gaze that is looking out, a revelation of a world. Or how it is that the elements of the visual field have secondary qualities such as colour that do not belong to the material world. Or how items in the field of experience are both unified as a landscape and, at the same time, available for separate attention. And then there are memories that refer explicitly to a past time, though the material world (which presumably includes the brain) lacks the temporal depth of tense. Neurones at time t are confined to time t, while subjects such as you and me are haunted by other times. What is more, our moments are always directed towards a future populated with possibilities that may never come to pass.

Consequently, over the decades, and in different ways, I have been preoccupied with trying to reconcile two large, seemingly irreconcilable, facts: that brain activity is a necessary and, in some circumstances, even a sufficient, condition of consciousness; and that brain activity is utterly unlike consciousness. What is more, most brain activity is not associated with consciousness, even in areas that are associated with consciousness, such as the cerebral cortex.

Are there ways of reconciling these seemingly conflicting truths?

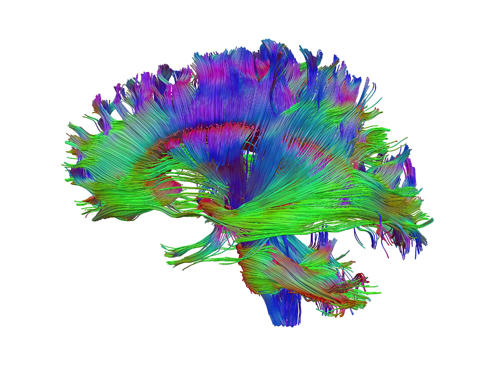

Healthy human adult brain viewed from the side, tractography. By Dr Flavio Dell’Acqua. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Licence: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The Identity Parade

Some philosophers argue that consciousness is different from brain activity if brain activity is the cause of consciousness rather than being identical with it. Unfortunately for this idea, the difference between these supposed causal partners, brain and mind, is more profound than seen elsewhere in nature. So although causally connected lightning and thunder are quite different, they have something fundamental in common, as both being manifestations of law-governed energy transformations. But the transition from lightning to the experience of the flash is nothing like this.

There’s another big difference, too. Neural activity is physically localised, but it doesn’t seem right to think of contents of consciousness in this way. When we think of transitive experiences such as sights and sounds, it is not clear where we should localize the experience, given that a conscious content is projected to something other than itself – its intentional object – such as the car or cloud you’re looking at or music you’re listening to. As for memories and thoughts, they clearly have no spatio-temporal proximity to their objects of the kind we usually associate with cause and effect.

If we abandon the idea of a causal relation between neural activity and conscious experience, the temptation is to return to variations of the mind-brain identity theory. One version, was famously espoused by the American philosopher Donald Davidson. It is called ‘anomalous monism’. It’s a monism because it argues that there is only one kind of stuff, namely matter. So individual mental events must be identical to physical brain events because there’s nothing else they could be. It is, however, ‘anomalous’, because, according to Donaldson, there are no lawlike relations between the mental and physical properties.

I have many times scratched my head over the second of these claims and have failed to see how it could be compatible with the first. At any rate, anomalous monism does nothing to alleviate the difficulty of identifying individual brain events with individual contents of consciousness given that they’re nothing like one another.

One of the most lucid contemporary defenders of the mind-brain identity theory is David Papineau. He denies that David Chalmers’ hard problem of consciousness – the problem of physically accounting for the what-it-is-likeness of consciousness – is at all hard. Hard problem consciousness, according to Papineau, “refers to brain processes that feel like something. Certain brain states are like something for subjects that have them.” (‘Materialism must be defended. Dualism is the problem not consciousness’, Institute of Art and Ideas, 12th March 2020). But this does not seem to meet the challenge. For a start, it by-passes the problem of there being subjects who ‘have’ brain states: in virtue of what are the brain states had and how shall we understand the subject who has them? Unanswered questions mount up as Papineau unpacks his position:

“There are just physical processes, all of which have the potential to become conscious by coming to play a role in intelligent reasoning systems … Consciousness doesn’t depend on some extra shining light, but only on the emergence of subjects, complex organisms that distinguish themselves from the rest of the world and use internal neural processes to guide their behaviour. Once these neural processes are present for these subjects they are like something for them… They are just ordinary physical states that happen to have been coopted by reasoning systems.”

The italics I have added indicate places where I believe Papineau’s response to the mystery of how neural activity could be identical with conscious experience actually highlights the mystery rather than solving it. ‘Playing a role in intelligent reasoning systems’ (and indeed, ‘intelligent reasoning systems’), being ‘coopted by such systems’, being ‘present for subjects’, and so on, are precisely the things that seem to be left unexplained by an identity theory. Indeed, they measure the width of the ‘explanatory gap’ that the mind-brain identity theory opens up.

At the end of his classic defence of mind-brain identity theory, ‘Mind the Gap’ (Philosophical Perspectives Volume 12, 1998), Papineau argues that the feelings that we associate with phenomenal consciousness (for example, the taste of cheese) are not additional to the feelings associated with non-phenomenal concepts such as ‘neural activity’: they’re merely two ways of describing the same thing, as when two words or phrases have the same referent (eg ‘Clark Kent is Superman’). He then asserts that “having feelings is just what it is to be in certain material states” (Italics mine). This formulation still has to explain the fundamental difference between the way the material object that is the cerebral cortex is supposed to be conscious in its material states, and the way other material objects such as stones, acorns, or indeed the cerebellum, are non-conscious in theirs. If the mind-brain identity theory is true, Raymond Tallis is the states of his brain in a way that a stone is not its states, but the idea does not account for the fact that there is something it’s like to be Raymond Tallis but there isn’t something it’s like to be a stone. In short, it does not explain why there are feelings associated with certain material states (of brains), but not with all the other states of the material world.

This, then, is where I am after sixty years of scratching myself at a place just above my cerebral cortex: feeling obliged both to embrace and to reject the identity of my consciousness with stuff going on in my brain. As for the alternatives – Cartesian dualism, property dualism, idealism, and panpsychism – they are even less attractive to me. Increasingly, it seems that I shall end my days not knowing the kind of creature I have been.

© Prof. Raymond Tallis 2025

Raymond Tallis’s latest book Prague 22: A Philosopher Takes a Tram through a City is now out in conjunction with Philosophy Now. See the review in this issue.