Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Non-Western Philosophy

Indigenous Australian Philosophy

Ross Naidoo looks at Indigenous thinking through a philosophical lens.

The Indigenous or Aboriginal peoples of Australia speak several hundred distinct languages, distributed across a vast continent. Although their unique worldviews developed over long ages and great distances, the same folktales, concepts and traditional beliefs can often be found in many different language groups. Academic study of these matters has usually been the preserve of anthropologists, but can philosophy perhaps raise our understanding of Indigenous belief systems? To explore this question, I will be seeking to categorize their culturally specific wisdom under Western, and to a lesser degree non-Western, philosophical frameworks. At the end of the article I will suggest a return to the exploration of the sacred, as this is the foundational basis of Indigenous philosophy.

A scar tree

Aboriginal scar tree © Kazadams 2012 Creative Commons 3

In an introductory essay on Australian Indigenous wisdom, I’m clearly not trying to capture the minutia and vastness of more than 50,000 years of the evolution of Indigenous wisdom. But it is valuable to use a philosophical framework that itself has over 2,500 years of continuous debate, speculation, and (occasionally) proof, to examine it.

Specifically, I will attempt to describe an Australian Indigenous philosophy from both analytical and continental perspectives. These are currently the two main schools of philosophical thought in the West. Indigenous philosophy aligns more with continental modes of thought than with those of analytical philosophy. The analytical framework might be said to be focused more on the analysis of concepts, therefore displaying less interest in large-scale metaphysics. This is not to say that striving for conceptual clarity is unimportant here. One authority, W.E.F. Stanner, has argued that understanding Indigenous Australian thought has been held back by “our abysmal ignorance of the deeper semantics of Aboriginal languages, including the secret languages often used by ritualists” (‘Some Aspects of Aboriginal Religion’ by W.E.H. Stanner, in Max Charlesworth ed. Religious Business: Essays on Australian Aboriginal Spirituality, CUP, 1998). Yet Indigenous philosophy is best viewed through a continental lens because that’s more concerned with issues existential and metaphysical than with snapshot analytics. In fact, however, the Indigenous philosopher has more in common with pre-Socratic and Indian philosophers than with either brand of contemporary Western philosophy. The similarities, I think, have much to do with the use of an oral tradition to propagate wisdom.

Indigenous Metaphysics & Epistemology

Crucial to understanding how a metaphysics, or understanding of the nature of reality, might be characterized from an Indigenous perspective, we must first acknowledge that the mythology of all groups – Greeks, Indians, Persians, Africans, Indigenous Americans, as well as the Indigenous peoples of Australia – has an underlying wisdom or philosophy, which can be construed from it through either direct or metaphorical interpretation.

Looking specifically at Australian Indigenous mythology, we see first the idea that the world is not chaotic, but beneficial towards human beings. In general, there’s a ‘life force’ or spiritual power that results in the manifestation and sustenance of the physical world and all that constitutes it: the terrain, waterways, climate, and all biological life, including humanity. We also see recognition of both the spirit and the physical body as having inherent value. So a human being is both of spirit and a physical source that engages with an organized cosmos that’s neither capricious nor malevolent.

This basic model of reality is in some ways like René Descartes’ model in his Meditations (1642). There he asserts the existence of three substances, each characterized in terms of an essence. The first two are mind and matter. These are equivalent to spirit and body in Indigenous metaphysics. The Stoics also referred to spirit, the vital soul or creative force of a person, in Greek as pneuma (also meaning ‘breath’ or ‘wind’) or in Latin spiritus, from spirare, ‘to breathe’. Similarly, for Indigenous peoples, spirit is what animates the physical, mental, and emotional body, and it’s linked to the breath, because without breath there is no life.

However, the third and most fundamental substance for Descartes is God, whose essence he describes as ‘supreme perfection’ (Meditations on First Philosophy 7). In Descartes’ metaphysics, we might say that God is the only genuine or independent substance – which, put most basically, means the only being capable of existing on its own, with all others being dependent on God for their creation, maintenance, and dissolution.

An Australian Indigenous metaphysics is in alignment with Descartes’ thinking here, if one replaces God with Spirit: pre-extant or necessary Spirit produces the land, its life, and humanity. On this basis, all law has authority because it’s based on a connection with Spirit, and Spirit is the genuine ultimate reality and the primary cause. For the laws, this cause works through culture and tradition, as the various sacred traditions are transmitted through succeeding generations and among those around.

Rock art

Little Mertens Falls, Mitchell River National Park, Kimberley Public Domain

Crucial to this picture is the so-called ‘Dreaming’, or to be more exacting in English, ‘the Every-where and When’. This concept encompasses the past, the ever-present now, and the future. It is an attempt to ground the metaphysical beginning and the ever-present now through personal experience in the material cosmos. We might say that our current ever-present experiences express the ongoing process of Dreaming as a creative principle in and of the cosmos (for more on this, see ‘Elements of Australian Aboriginal Philosophy’, Oceania, Vol. 40, No. 2, A.P. Elkin, 1969).

The nature of our experiences in the world has intrigued philosophers and poets throughout history. Plato argued that it was never possible at any given moment to prove “whether we are asleep and our thoughts are a dream, or whether we are awake and talking with each other in a waking condition” (Theaetetus). His idea is that we might be characters in a dream. In classical Indian philosophy and poetry, the cosmos is also often determined to be unreal, or a dream of the Creator, who materializes the dream through our finite experiences.

Perhaps part of the intent of the dream concept is to increase our awareness of the impermanence and flux of the physical world. The pre-Socratic philosopher Parmenides of Elea specifically expressed ideas related to problems of being and change, saying that there is no change, just unchanging being, so that change, and the very world we experience, is an illusion. After Plato wrote his Republic, in which he used his theory of Forms to explain continuity and change, Parmenides’ ideas fell out of favour. Yet the development of quantum physics, and attempts to interpret what it means, have spurred a renewed interest in what he had to say.

Indigenous philosophers could well find some fellowship with Parmenides. Neither he nor they wrote down their thoughts; rather, their students carried their stories from generation to generation via oral tradition. However, regardless of the impermanent nature of our physical bodies and our physical surroundings, in our hearts we do not believe that the physical world is an illusion. But the idea does allow us to imagine ourselves in a situation in which we might believe it.

Most importantly for an Indigenous metaphysics, the Dreaming is what the anthropologist A.P. Elkin in 1969 called “the ever-present, unseen ground of being, of existence” (for more, see Australian Aboriginal Philosophy, Max Charlesworth, 2000). But Indigenous thinking is not a ‘self-conscious detachment towards myth’, as Charlesworth puts it. Rather, it is the conscious placing of one’s guiding spirit over the material essentials. Through this, ‘being’ is developed. Perhaps the concept that most captures the sense of being in ‘Every-When and Where’ from a Western philosophical perspective is perhaps that of Martin Heidegger’s Dasein: the idea of an ever-present human consciousness that is ‘thrown into’, rather than choosing, its world. Yet in Indigenous thinking, ritual, meaning, and purpose are all interlinked in what’s important to one’s being, to the sense of self that precedes our physical, intellectual and emotional selves, and to the pre-source of all creation. All physical and non-physical support come from the original source of the Dreaming. The Dream perpetuates the ‘Every-When and Where’ being and its here and now manifestation experienced by both the spiritual and physical self.

Dasein as ever-present conscious being is also somewhat like the Indigenous concept of deep listening called dadirri. Deep listening is the almost spiritual skill of being fully present. It’s based on a deep humility and respect for the subtle messages that are constantly flowing to the individual from the world and involves an inner quiet, a stilled silent awareness, which is waiting and available to everyone – a deep receptive love, if love were thought of as an infinite space that denies no entry. Deep listening is a creative spirit that occurs in silent calm action. Dadirri is reminiscent of Hindu meditation, in which yoga and dhyana are practised to recognize ‘pure awareness’ or ‘pure consciousness’, undisturbed by the workings of the intellectual mind – therefore forming a connection with one’s eternal self, otherwise called ‘the ever-present soul’.

We can call the country (or land) the first cause of physical things, in the sense of being the foundation that does not change, and so the constant through multiple interconnected interactions. Yet while our sense of being as awareness does not change, even from the first principles of the Creator Spirit, the country does; and as it does, so do the many varied geo-philosophies that manifest, linked to the local clans.

Finally, an Indigenous epistemology or theory of knowledge, would be about two interconnected philosophical ideas: it’s about the way the mind apprehends the world, and about the way the world is at any given moment. It’s first based on experiences of Dream or Spirit, the human, and the physical land; but more particularly, it is about the way illusion and reality are related, the way our minds affect the physical world, the way that world exists to our present minds, and the connections between those components. (It would also be a kind of religious parable, being an example of storytelling that endeavors to explain these things. But more than that, it’s also a meta-parable – a parable about parables – for it would also be a story about storytelling.)

The benign connectivity between the people and the land forms what Foley terms ‘a metaphysics of meta-patterns’. This is when numerous patterns flow together as a part of creation that communicates as it flows to those sensitive enough to perceive these patterns. For example, the applied indigenous philosopher does not need to physically see the crocodile eggs to know that they are ready to be harvested, as the presence of a specific kind of marsh fly communicates this message of knowing in real time.

The flow of meta-patterns to people is like a constant invitation by creation to participate in the constant flow of creation: it’s a constant prompting to be an active part with creation. These meta-patterns of life, interpreted as ever-present flows of information, are then available to be consciously gathered and shared culturally. These deep meta-patterns, which constantly inform human knowledge, are available to those who have the necessary levels of awareness and have adhered a ‘deeper listening’. Achieving dadirri is vitally important as a conscious state, then, in order that this meta-communication from the surroundings can be perceived.

Indigenous peoples accept that the source of all events is Spiritual, and as a by-product, accept limitations of knowledge as the result of their limited nature within creation, So they feel no need to flaunt their knowledge as a sign of intellectual superiority.

Image © Sylvie Reed 2025

A Proposed Ontology for Australian Indigenous Peoples

I base the following ontology, or scheme of what exists, on Dennis Foley’s ‘Indigenous Epistemology and Indigenous Standpoint Theory’ (Social Alternative, Vol 22, No 1, 2003). He writes “Indigenous philosophy has three interacting worlds: the Physical World, the Human World and the Spiritual World.”

The Physical World is the base, the land, the creation. The land is the mother, and we are of the land. We do not own the land, the land owns us. The land is also our food, our Spirit, culture, and our identity. The physical world includes the sky, land, waterways, and all living forms.

The Human World involves cultural knowledge, approaches to people, family, and rules of behaviour; ceremonies; and a capacity for change.

The Sacred World has foundations in the healing, both spiritual and physical, of all creatures. It includes the lore, the laws, their ongoing maintenance, the retention and reinforcement of oral history, and the care of country.

In short, the physical world and its ongoing events are a product of the ever-present Spirit in the ever unfolding Dreaming or Every-Where and When. Man is not the centre of this model: rather, at the centre is the ever-perpetuating Mother (the Mother as Divinity) – in Her most sacred when at play in creation.

Because Indigenous spirituality is based around the land and terrain of a specific group, the members of that landscape derive their spiritual values from specific terrain. They also believe that they’re connected to the absolute via the land. In this sense, Tony Swain suggests in A Place For Strangers (CUP 1993) that their philosophies can be termed ‘geo-sophical’; or put another way, Indigenous philosophy is a wisdom derived from the experience and inspiration of specific geography.

It’s important that this Indigenous ontology includes both spiritual events and the material world, and that the ongoing connection with the land and its events is seen as inseparable.

Aboriginal religious art Dun Deagh 2012 Creative Commons 2

From Metaphysics to Axiology

The Indigenous viewpoint treasures the earth beyond human life. The beyond has an inalienable relevance to life, birth, and death that engulfs the Spiritual and the material Mother in a perpetual cyclical pattern. Professor Japanangka Errol West also suggests that the Indigenous worldview recognises a reverential connection between the spiritual realms of the universe and the material platform of the earth – or if you prefer, of the treasured Mother acting in accord with peaceful life.

An Indigenous axiology or theory of values promotes a synergy of interwoven complexity, covering the land, the animal and plant species, and the human, to promote both human and ecological benefit – indeed, benefitting all involved. This connectivity suggests a symbiosis or mutuality between self and others, where, axiomatically, a care for oneself means care for the country. The Indigenous response of care is in fact an ever-present communication between the ecology and humans, which permits the co-existence of all species in a kind of mutual care. We as a species could well learn from this attitude.

Any attempt to model an Indigenous system of values must involve at least the six areas below. They should be considered when trying to understand Indigenous pathways for value acquisition and decision-making:

(1) Sensing or intuiting that the world is made up of interconnected patterns (expanding beyond the intellect to include mature sensing);

(2) A focus on close intimate observations and pattern testing (empathy and compassion combined with intellect);

(3) Respect for other living things as inclusive participants, with mutual benefits (a compassionate respect for life);

(4) Awareness beyond the self of life being both for the individual and for others (evolving from I, to You, to We, to Us);

(5) A consciousness awareness expanded beyond the self through various levels of being; in other words an epistemological model incorporating the Self, the World, and the Sacred.

(6) A desire to participate in the meta-patterns, and in the ever-present creative process; to participate, in fact, in the ongoing flow of creation.

At the heart of this is the idea of interconnectivity and communication between land and human being, which results in a knowing that aligns with action. This creates mutual benefits for all the participants in the ecosystem, whether humans, animals, plants, and country – in a type of deep mutualism.

The maintenance of the land ensures that constant ever-flowing (meta-)communications continue to be received from the ecosystem. If the land is lost or destroyed, so is the source of the information. When the ecology is lost, so are the communications, and thus the benefits of country. Thus, the idea exists within Indigenous Australian Peoples cultures that benefits always flow from the world, and everything ought to benefit the world so that humans can benefit. This idea is also occasionally found in Western philosophy. For instance, Freya Mathews argues in For Love of Matter: A Contemporary Panpsychism (SUNY Press, 2003) that there are two main characteristics to life: one is its desire for its own becoming (conatus); the other a desire for connectivity (orexis). These desires are connected in that life must and wants to live both for itself and for others.

The struggle of the impermanent human is first to not forget the necessity of Spirit in all one’s mundane endeavors, just as a driver of a vehicle must always be aware that they’re travelling on a road. And the collective journey is far more important than the individual’s atomised content.

In a nutshell, Indigenous peoples’ ethics is one of connection and benefit through complex recursive relationships that occur within specific country. Although we’re not speaking about a closed system, it has a self-creative circularity nevertheless. This is not a random activity. Its main purpose is to nurture an individual who is ‘ready to participate in the realness of the world’ (‘An Indigenous Philosophical Ecology’, The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 16:3, Deborah Rose, 2005).

To reiterate, the desire of ‘being’ for Indigenous Peoples is to participate in the eventfulness of a living land. Yet whilst this approach may rely on humans, it does not prioritise human needs and desires. The ecology does not activate autonomous human agency; rather, it calls the human into activity with itself. This means that, rather than human beings taking action autonomously (and randomly), they are in fact called into action by the World. This is a vastly different model of agency and self-determination than exists in Western ideas of identity. Indeed, this paradigm is more in line with Indian philosophy than Western. In Indian philosophy, the focus is on aligning with the activities of the Creator and his world first, and once this is achieved, the Creator naturally fulfills your desires. This differs greatly from the modern liberal materialist Western concept, of individual creativity and agency claiming to be operating within a random universe.

In conclusion, this short review suggests that Indigenous Peoples should reconnect with what is sacred in their historical traditions. In so doing, they may develop and celebrate a renaissance of their ways of knowing, and perhaps begin to redress the historical dispossession of their land and culture.

© Rossven J. Naidoo 2025

Ross Naidoo is a Food Science Liaison Officer working at state government level in Australia. He has postgraduate qualifications in International Business and in Western Philosophy with a focus on metaphysics and its application to traditional belief systems.

Australian Indigenous Philosophy

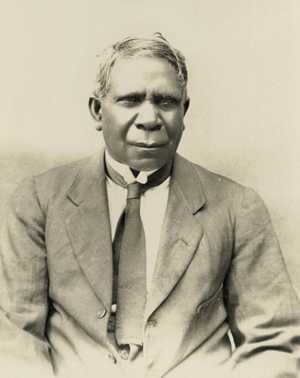

As the traditions of Australia’s Indigenous peoples developed gradually and were transmitted orally over countless successive generations, we generally don’t know the names of the originators of their philosophical concepts. We do however know some of the individuals who have taught anthropologists to understand these traditional systems of ideas.

State Library of New South Wales

David Unaipon (1872-1967) was a polymath: a thinker, author, and inventor who was a member of the Portaulun branch of the Ngarrindjeri people in South Australia. At the age of 13 he left school and worked as a servant to C.B. Young, who encouraged his interest in philosophy, science and music. Known as ‘Australia’s Leonardo’ due to his wide range of interests and knowledge, in his lifetime he took out 19 patents for his various inventions, including pre-World War I drawings for a helicopter design based on the aerodynamics of the boomerang, and a design for a rotary-geared sheep-shearing handpiece that became the basis for most modern sheep sheers. He became an active campaigner for Aboriginal rights, and is best known as a student of Aboriginal mythology. In 1930 he compiled his version of the legends, traditions and customs that had been passed down to him into one text called Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals. Since 1995 his portrait has been featured on the Australian $50 note.

Big Bill Neidjie (1913-2002) was an elder of the Gaagudju people. Though having little formal education, he acquired great knowledge of the land, his people and the traditional culture from his own community. Later in life he became the senior elder of Kakadu and was seen as a custodian of the land, helping set up Kakadu National Park. A recurring theme in his life was preservation and as the last surviving speaker of the Gaagudju language, as he grew older he realised a lot of his people’s traditional stories and culture would die with him. He made the courageous decision to break the taboo against passing traditional secrets to non-initiates and with the help of anthropologist David Kemp, published two books documenting this. This was done in the hope that his culture would one day thrive again.

The brothers Mick Dodson (b.1950) and Patrick Dodson (b.1948) are members of the Yawuru people. Mick is a barrister and academic, and Patrick is a former senator. They have contributed much to the academic community’s understanding of Aboriginal law and philosophy.

Alex Marsh