Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Centennial of the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial

Tim Madigan on the creation and the evolution of a legend.

The prominent philosopher Lewis White Beck (1913-1997), a leading authority on Kant’s work, was born in Griffin, Georgia, in the heart of the Bible Belt. Like many Americans of that era, he had vivid memories of a seminal event in the mid-Nineteen Twenties: the trial of John T. Scopes for the crime of teaching evolution in the state of Tennessee. Beck writes:

In 1925, I was awakened from my dogmatic slumber by newspaper accounts of the ‘Monkey Trial’. John T. Scopes was found guilty of breaking a law of the state of Tennessee prohibiting the teaching of the theory of evolution. Reading accounts of both sides of the trial made me admit that Mr. Scopes was indeed guilty – there was no question about that – but made me see that the law itself was foolish. I bought and read The Origin of Species, which confirmed what became a new dogmatism for me. . . . By the age of twelve, my education as the village atheist was essentially complete (Falling in Love with Wisdom: American Philosophers Talk about Their Calling, 1993, p. 13).

Beck was by no means alone in finding the trial to be a legal farce, and yet ultimately a vindication for the theory of evolution as well as a defeat of Biblical Fundamentalism. It remains a milestone in United States legal history. And yet, the trial itself was, to say the least, unorthodox.

It is safe to say that unlike Professor Beck, who had firsthand knowledge about the trial, most people’s awareness of it comes primarily from a single source, the 1955 play Inherit the Wind as well as the 1960 film version of that work. Given that 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of the trial it’s not surprising that the play is currently being revived throughout America. I myself recently attended an excellent production starring actor and former U.S. House Representative Fred Grandy and directed by his Love Boat co-star Ted Lange.

Ironically, though, Inherit the Wind was not originally written to reopen debate over the Scopes Trial. The playwrights, Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee, were both strong social libertarians. Another of their collaborations, for instance, is entitled The Night Thoreau Spent in Jail, and deals with the topic of civil disobedience. They first conceived writing a play inspired by the Scopes trial (the title taken from Proverbs 11: 29, “He that troubleth his own house shall inherit the wind”) in 1950, during the height of the McCarthy hearings, when many Americans had their loyalties questioned and were accused of being communist sympathizers or even traitors. The playwrights were appalled at the ways in which Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy and other U.S. government officials used the law to try to silence dissent. Much like Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, written around the same time, the two collaborators utilized an event from the distant U.S. past to reflect upon the present-day situation.

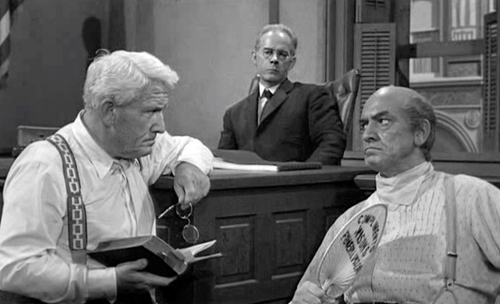

Spencer Tracy as Harry Drummond and Fredric March as Matthew Brady in a courtroom scene from the 1960 movie Inherit The Wind

Still from a trailer for Inherit The Wind, 1960

Lawrence and Lee were careful to make clear that their play was not a literal depiction of the Scopes Trial. They changed the names of the main participants (John Scopes for instance, became Bert Cates, William Jennings Bryan became Matthew Harrison Brady, Clarence Darrow became Henry Drummond, and H.L. Mencken became E.K. Hornbeck). While thinly disguised, the characters were not meant to be one-to-one correspondents to the real-life individuals who participated in the 1925 trial. The playwrights wrote in their introduction to the work that “ Inherit the Wind is not history. The events which took place in Dayton, Tennessee, during the scorching July of 1925 are clearly the genesis of this play. It has, however, an exodus entirely its own.” They conflated events, simplified issues, and overemphasized the roles of Darrow and Bryan, leaving out several other important attorneys involved with the case. Most importantly, they changed the significance of the trial itself, making it seem as if the citizens of “Hillsboro” (standing in for Dayton) were universally religious fundamentalists, which was not the case. For those who wish to know more about the actual trial, I highly recommend Brenda Wineapple’s 2024 book Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial that Riveted a Nation.

As the play begins, Bert Cates is in jail. His fiancée (the daughter of the local minister) visits him there and pleads with him to admit he was wrong to teach evolution. Meanwhile, outside the jail cell, the local citizens are up in arms against him, and want to ride him out of town on a rail. As Lawrence and Lee well knew, none of this was true. Scopes never spent a day in jail, he was not engaged to the local minister’s daughter, and the townspeople – while not necessarily pro-evolution – were on friendly terms with him. Indeed, the town leaders had asked him to be the defendant for a trial which they hoped would bring national attention to Dayton, thus helping the local economy, and were grateful to him for agreeing to do so.

Wineapple details the reasons why the state of Tennessee had passed the so-called Butler Law, forbidding the teaching of evolution, and how the little town of Dayton, with barely 3,000 citizens, became the focal point of protest against it. Named after representative John W. Butler, who first proposed it, the law stated: “That it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower form of animals.” The governor of Tennessee, who was actually in favor of teaching evolution, signed it, since he needed the legislature to pass other laws he considered more important, including one for furthering financial support for the state’s growing educational system. Like other politicians at the time, he hoped that the law would never actually be put into effect, but his hope was quickly squashed.

There was a confluence of events in the mid-1920s that led to the Scopes Trial. First of all, the rise of the public school system made education itself a controversial topic. The number of pupils enrolled in American high schools had leapt from about 200,000 in the 1890s to over two million in 1920. Home schooling was becoming a thing of past, and laws were enacted which mandated compulsory schooling for children throughout the United States. Parents and ministers feared what the pupils were being taught in these nonsectarian schools. Who had the right to determine the curriculum?

Secondly, the rise of the Fundamentalist movement in response to modernism and ‘higher criticism’ of the Bible was another phenomenon of the Nineteen Twenties. In 1919, 6,000 conservative Christians attended the World Christian Fundamentals Association (WCFA) conference. Originally founded to defend so-called Biblical fundamentals in churches and divinity schools, the WCFA, as well as other related organizations, quickly saw the public schools as the new battleground for defending the faith, with evolution as the chief enemy. This was the impetus for enacting legislation such as the Butler Law. Sensing the growing political clout of the newly roused and newly named ‘Fundamentalists’, elected officials took the hint and started passing such laws, hoping that would be sufficient to appease the movement.

A third strand leading to the Scopes Trial was the rise of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). At the end of the Woodrow Wilson Administration, in response to the Communist Revolution in the Soviet Union and the fear of a similar uprising in the United States, political radicals were arrested or exiled. The Socialist leader Eugene Debs was imprisoned for criticizing America’s entry into the First World War, the anarchist firebrand Emma Goldman was deported to Russia, and U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer launched a national campaign – along with his ally, the very young J. Edgar Hoover – to weed out Bolsheviks and other ‘unAmericans’ throughout the land. This Post-World War I period has come to be called ‘The Red Scare’, and has many similarities with the post-World War II McCarthyism era. In response to the Red Scare, the ACLU was formed, to defend freedom of dissent and the rights of minorities. Its leaders particularly feared the way that the tyranny of the majority could dictate what could be taught in the nation’s schools. They were looking for a test case to combat the criminalization of teaching evolution, which they saw as the first wedge in a growing campaign to destroy educational freedom. The ACLU wanted a Supreme Court decision, which would standardize the question of whether educators or legislators determined curriculum content throughout the United States. They advertised for a test case, and finally found one – or so they thought – in Dayton.

The 2025 Scopes Trial Centennial Conference took place on July 18-20, 2025 in Tennessee, close to the location of the original trial. The courthouse can still be seen, and there are statues of Darrow and Bryan. Our correspondent Kenneth Marsalek was there, and took this photo of a conference attendee passing Darrow’s statue. You can read more about the entire program of centennial celebrations at scopes100.com.

© Kenneth Marsalek 2025

Edward J. Larson, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1997 book Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion, argues that the state of Tennessee was not a Fundamentalist hotbed. The citizens of Dayton were primarily Methodist, not Baptist, and many had opposed the Butler Law. But the town fathers saw a chance for national publicity by agreeing to make Dayton the site of the proposed ACLU test case. John Scopes was asked to be the defendant by the local prosecutors, including his friend Sue Hicks (a man named after his mother and supposedly the basis for the Johnny Cash hit song ‘A Boy Named Sue’). Scopes himself was a native of Kentucky who was only a substitute science teacher, and he was planning to leave Dayton for good in the fall. He was asked to be the defendant because the town leaders didn’t want to imperil the career of the full-time science teacher. Ironically, Scopes wasn’t sure if he had actually taught the theory of evolution, but supposed that he must have done so, and good-naturedly agreed to accept the challenge.

But it is the legal antagonists, rather than Scopes himself, who are the most famous individuals in the trial, particularly defense attorney Clarence Darrow and prosecuting attorney William Jennings Bryan. Both were celebrities of the day, noted for their rhetorical skills and their own love for the limelight. And yet, neither of them was initially involved in the decision to hold the trial at Dayton. In fact, their participation upset the plans of both the Dayton town fathers and the ACLU, neither of whom anticipated just what a circus the trial would become. The publicity for Dayton became mostly negative, thanks in part to the vituperative writings of Baltimore newspaperman H.L. Mencken, and the ACLU’s own involvement in the case was overshadowed by the towering presence of Darrow.

Henry Drummond, the Inherit the Wind character obviously modeled upon Darrow, is the hero of the play. But Darrow had in reality invited himself onto the Dayton defense team. Most of the ACLU leaders didn’t want him involved. In their view, he was too controversial. Just the year before, he had successfully defended two child murderers, Leopold and Loeb, which had made him a vilified figure in the eyes of many. More to the point, Darrow was a vociferous agnostic, who delighted in making fun of organized religion. He saw the upcoming Dayton trial as a chance to focus attention on the ridiculousness of Biblical fundamentalism; the ACLU, on the other hand, wanted to contest the state’s right to dictate what could be taught in general. They didn’t want to antagonize religious believers, and had devised a legal strategy that would avoid the religious controversy. Darrow most decidedly wanted to make religion the focal point. After much internal debate, the ACLU was forced to accept Darrow on its legal team, after he made an end-run around them by getting Scopes to agree that he wanted the famed ‘Attorney for the Damned’ to represent him.

In a somewhat similar fashion, William Jennings Bryan joined the prosecution by also essentially inviting himself onto the team, after letting the national press know that he would be delighted to help out. Bryan was notorious for his ability to generate publicity, and had become the leading critic of ‘Darwinism’ in the United States, so he seemed a natural to be involved in the case. While the Inherit the Wind character Matthew Harrison Brady comes across as something of a blowhard, Bryan himself was a more complicated figure than the play presents. As Michael Kazin points out in his 2007 biography A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan, he was a champion of many progressive social causes and a defender of the rights of the dispossessed. In fact, his nickname was ‘The Great Commoner’, and for millions of Americans he represented the little man in the battle against Big Business and unbridled capitalism. A three-time unsuccessful presidential candidate, Bryan was a democrat with a capital ‘D’. As a social reformer, he believed strongly in direct political action, and advocated the view that citizens had a right to decide what should be taught in the public schools. A pacifist, he had resigned as Wilson’s Secretary of State when it became clear to him that the president was leading America into the First World War. While undoubtedly a devout Christian, Bryan was not himself a fundamentalist, i.e. a literalist when it came to understanding the Bible. For him, the teachings of Christ needed to be applied to making the world a better place. His antagonism to evolution was directly connected with his opposition to so-called Social Darwinism, the belief that poverty was a character flaw which should not be relieved through governmental intervention. In fact, he and Darrow had often been on the same side politically, over such issues as women getting the right to vote, support for labor unions, and the fight for the direct election of U.S. senators. There was, however, one topic other than evolution over which they vehemently disagreed: Prohibition. Bryan had been in the forefront of the campaign to pass the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, prohibiting the sale of intoxicating liquors. Darrow was an opponent of the recently enacted amendment, as was the hard-drinking Mencken, whose sarcastic articles about the Scopes trial played a large role in making both Bryan and the citizens of Dayton look like yahoos. Mencken, who is depicted in Inherit the Wind as the cynical E.K. Hornbeck, came to Dayton to cover the trial, but didn’t stay until its end, as Hornbeck does in the play.

Inherit the Wind does quite accurately depict the most memorable moment of the trial – Darrow’s cross-examination of Bryan, in which he lured the increasingly flustered Bryan into defending, or at least trying to explain, some of the more questionable stories from scripture, such as Cain finding a wife, Joshua making the Sun stand still, and Jonah being swallowed by a whale. Lawrence and Lee took much of this scene directly from the actual trial transcripts. However, Darrow’s strategy ultimately didn’t really have much bearing on the case, and went against the wishes of his ACLU allies. The judge struck Bryan’s testimony from the record, and the jury found Scopes found guilty. This, after all, had been the ACLU’s desire in the first place, for without a guilty verdict they would not have been able to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. Darrow’s shenanigans, while making for great theater, were beside the point, and helped to make Bryan a martyr figure for fundamentalists, particularly when the latter died just a few days after the trial’s end.

The debate continues over who really ‘won’ the Scopes trial. Upon appeal, the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld the Butler Law, but cleverly overturned the Scopes conviction on a technicality. Thus, the ACLU was unable to take the case further. And yet, while other states had also passed similar anti-evolution laws, eventually they were all overturned. By the time Lawrence and Lee came to write Inherit the Wind, the anti-evolution crusade seemed a thing of the distant past. For them, the teaching of evolution was a settled issue. The Scopes Trial itself became a metaphor for the continuing battle over intellectual freedom. As they wrote in their introduction to the play: “The collision of Bryan and Darrow at Dayton was dramatic, but it was not drama. Moreover, the issues of their conflict have acquired new dimension and meaning in the thirty years since they clashed at the Rhea County Courthouse. So Inherit the Wind does not pretend to be journalism. It is theatre. It is not 1925. The stage directions set the time as ‘Not too long ago’. It might have been yesterday. It could be tomorrow.”

It is ironic that the play remains relevant today in a way Lawrence and Lee themselves did not anticipate. By the time they were able to mount the play on Broadway, in 1955, the worst of McCarthyism was over. And when the movie version, starring Spencer Tracy as Drummond and Fredric March as Brady, came out in 1960, the Communist scare itself seemed a thing of the past.

And yet, the issues debated at the Scopes Trial in the mid-Twentieth Century are once again front-page news in the mid-Twenty First. Now, instead of laws outlawing the teaching of evolution, equal time is being demanded for the teaching of ‘Intelligent Design’ (ID), which is claimed to be scientific. Unlike Darrow, many of today’s defenders of evolution are unskilled in rhetoric, while opponents continue to have Bryan’s gift of persuasion.

In contemporary America, not just in the Deep South but throughout the country, there is often a de facto omission of discussing evolution in textbooks and courses, in order to avoid controversy. Home schooling is also an increasing phenomenon, particularly among conservative Christians. And in 2025 the public school system itself is one of the targets of political conservatives, just as it was in 1925, and for much the same reasons. Most frightening of all is the political alliance between the Republican Party and religious Fundamentalists, which has helped to polarize the United States along sectarian lines, and led to renewed attacks on the separation of church and state.

What would Bryan have thought about this state of affairs? One never knows, but it is important to remember that he was a Democrat in all meanings of that term, as well as a vocal critic of Big Business. The alliance of Biblical inerrancy with rapacious capitalism would surely have disturbed him. A type of ‘Social Darwinism’ has been revived, with the view that the Godly will prosper economically and no social safety net is needed for those unable to make it in the struggle for survival. On the other hand, as Wineapple, Larson, and Kazin all demonstrate, Bryan – unlike Darrow – was a White Supremacist who opposed integration (one of Scopes’ other lawyers, Arthur Garfield Hays, would later write the ACLU’s brief in support of the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education case). His populism was not allied with the fight for racial equality, and, as critics at the time such as W.E.B. Du Bois noted, many opponents of evolution were appalled by the view that humans might have come from a ‘common stock’ originating in Africa. Behind many of the religious objections to evolution there lay a virulent racism.

What can be done to address the contemporary campaign against the teaching of evolution? Interestingly enough, Inherit the Wind provides one answer. It remains an important play precisely because it continues to generate discussion on the need to defend freedom of thought. At the end of the play, Cates asked Drummond if he had won or lost.

Drummond: You won.

Cates: But the jury found me –

Drummond: What jury? Twelve men? Millions of people will say you won. They’ll read in their papers tonight that you smashed a bad law. You made it a joke!

Cates: Yeah. But what’s going to happen now? I haven’t got a job. I’ll bet they won’t even let me back in the boarding house.

Drummond: Sure, it’s gonna be tough, it’s not gonna be any church social for a while. But you’ll live. And while they’re making you sweat, remember – you’ve helped the next fella.

Cates: What do you mean?

Drummond: You don’t suppose this kind of thing is ever finished, do you? Tomorrow it’ll be something else – and another fella will have to stand up. And you’ve helped give him the guts to do it!

Little did Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee realize, when penning their protest against McCarthyism and anti-Communism, that the ‘something else’ coming down the road would be exactly the same battle they were using as a metaphor. Inherit the Wind remains a timely work.

© Prof. Timothy J. Madigan 2025

Tim Madigan is Professor of Philosophy at St John Fisher University. His greatest regret is that he never appeared as an actor on The Love Boat.