Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Quantum Physics & Indian Philosophy

Punit Kumar and Sanjeev Kumar Varshney look into entangled worlds.

Our deepening exploration of the quantum world reveals intriguing parallels between subatomic phenomena and Indian philosophy. While each offers a distinct perspective, together they weave a narrative that challenges traditional boundaries and redefines our understanding of reality.

Quantum physics, with its principles of superposition, entanglement, and the observer effect, has disrupted classical notions of a deterministic universe. Quantum pioneers such as Heisenberg, Schrödinger, and Bohr revolutionized science by introducing both uncertainty and the observer as intrinsic aspects of reality. But questions remain. For instance, does observation merely reveal the quantum world, or does it actively shape it – and how? This enigma highlights the intricate relationship between consciousness and quantum mechanics, sparking a dialogue that transcends conventional scientific inquiry.

Against this backdrop some of the central ideas from Indian philosophy provide profound insights. Traditions such as Vedanta and Samkhya have long explored the interconnectedness of all things and posited consciousness as the essence of reality, so these frameworks resonate deeply with themes emerging from quantum physics, thus bridging ancient wisdom and modern science.

The Quantum Frontier

Quantum mechanics is the branch of physics that explores the behaviour of matter and energy at the smallest scales, such as atoms and subatomic particles. It marks a significant departure from classical physics, which still accurately describes the motion of larger objects like billiard balls or planets. One of quantum mechanics’ most profound implications is its challenge to our understanding of reality. For instance, wave-particles existing in a superposition of states until observed (as one reading of quantum mechanics maintains) makes observation a crucial factor in experimental outcomes, in that it is thought there is no specific state a quantum entity is in until it is measured to be in that state. This defies traditional notions of objective reality, pushing us to reconsider what is real.

Despite its counterintuitive nature, quantum mechanics has been remarkably successful in describing the behaviour of matter and energy at microscopic scales; so it has not only reshaped our understanding of the universe, but also fuelled advances in science and technology from quantum computing to medical imaging. Even the diodes in your computer wouldn’t work without the quantum tunnelling effect. As a cornerstone of modern physics, quantum mechanics continues to drive exploration.

Cosmic Sunflower by Paul Gregory

Indian Philosophy: A Non-Dualistic Vision of Reality

Indian philosophy is a deep and ancient tradition that includes many different schools of thought. Although these schools have their own unique ideas about the world, knowledge, and life, they often agree on some key points. Many of them talk about ‘non-duality’ or ‘oneness’ – the interconnection of all things – or about the importance of consciousness in understanding reality. These shared ideas have shaped India’s intellectual and spiritual journey for thousands of years.

One of the most important ideas in Indian philosophy comes from the ancient text known as the Advaita Vedanta, which is itself based on the teachings of the Upanishads, and was later developed by the saint Adi Shankaracharya. According to the Advaita school, ultimate reality (brahman) is infinite, eternal, and beyond time, space, or change, has no shape or qualities, and is the source of everything. Moreover, the individual soul (atman), is said not to be separate from reality; on the contrary, Advaita Vedanta teaches that soul is the ultimate reality – meaning that the true self inside each person is the same stuff as ultimate cosmic reality. This truth, however, is hidden from us by illusion (maya) – which is not complete falsehood, but a power that makes the one reality appear as many. Because of this, we see differences, changes, and separations in the world, even though everything is actually one. Liberation (moksha) comes as a person realizes this non-dualistic truth and understands that their true self is ultimate reality. This realization ends the cycle of death and rebirth, and leads to eternal peace and freedom.

In contrast to Advaita’s non-dualism, the Samkhya school presents a dualistic view of reality. It talks about two basic elements: nature or matter (prakriti); and pure consciousness (purusha). Matter has balance (sattva), activity (rajas), and inertia (tamas), and is responsible for all physical and sensational experiences. Consciousness, on the other hand, in its original state is silent, eternal, and watches everything without getting involved. According to Samkhya, our suffering happens because consciousness forgets its true nature and starts to identify with the changing world of matter. Liberation (kaivalya) then happens when consciousness realizes that it is separate from matter and stops being attached to it. So although Samkhya does not believe the non-dualism of Advaita, it also considers consciousness as central, and believes that true freedom comes from self-awareness.

Buddhism, especially the Mahayana tradition, brings in another deep idea, of emptiness (sūnyatā) – specifically meaning that nothing has a fixed, independent nature: everything we see or experience exists only because of other things, and all of it depends on causes and conditions. This idea is called ‘dependent origination’ (pratītyasamutpāda). Nothing exists on its own. For example, a tree exists only because of the seed, water, sunlight, and many other factors. On this view, even the idea of a permanent self is false. Rather, everything is changing and connected, and realizing this emptiness leads to wisdom, compassion, and freedom from selfish desires. According to Buddhism, enlightenment comes when we let go of ego and desire, and understand that everything is part of a bigger whole.

Although Advaita Vedanta, Samkhya, and Mahayana Buddhism differ in profound ways, they all invite us to look beyond the surface and question the materialist view that the world is made only of physical stuff. Instead, they focus on consciousness; interconnectedness; the idea that the world as we see it is not the full truth; and the claim that through understanding this, people can attain peace and liberation from suffering.

Harmonizing The Realms

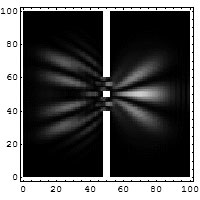

Quantum slits JC Benoist 2006

In quantum mechanics, the quantum system being observed or measured is described by a mathematical tool called the ‘wave function’. The wave function describes all the possible outcomes that the quantum system might be observed to display, such as where an electron might end up on a screen. However, these possibilities remain unrealised (or ‘probabilistic’) until someone observes the system. It is only at that point that the one specific result appears. This is a process known as ‘wave function collapse’.

This idea bears similarities to the concept of maya in Advaita Vedanta. According to this philosophy, it is illusion that makes the world appear full of differences, movement, and separation. The world we see and interact with is not completely false, but it hides the true, undivided nature of existence. But just as the wave function collapses into a definite state when a quantum entity is observed, the illusion disappears when a person gains knowledge. And in both cases – whether in physics or in the path to spiritual awakening – the observer plays a key role.

The observer effect is one of the most puzzling parts of quantum theory. It says that the act of observing a quantum system changes its behaviour. Some interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as the Copenhagen interpretation or Wigner’s views, even say that consciousness (that is, conscious observation) causes the wave function to collapse into a single reality. This means the observer isn’t just watching reality, but actually helping shape it through the very act of observation. This idea can be connected to the Advaita Vedanta teaching that consciousness is not created by the brain, but is rather, the basic foundation of all existence (including brains). So in different ways, both quantum physics and Indian philosophy suggest that reality is not just out there waiting to be seen by consciousness, but exists through consciousness. (The noted quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg saw this link too, noting that the Upanishads recognize consciousness, not matter, as the source of everything.)

Another fascinating idea in quantum physics is entanglement. When two wave-particles become entangled, they stay connected no matter how far apart they are, and changing one instantly affects the other. This appears to conflict with Einstein’s theory of special relativity, which say that nothing can affect something else faster than the speed of light.

Entanglement shows that the universe is deeply interconnected in ways we don’t understand. This again mirrors ideas in Indian philosophy, especially in Buddhism and Vedanta. The Buddhist teaching of dependent origination says that nothing exists on its own; everything exists through relationships. Similarly, Vedanta teaches that everything is part of one interconnected reality. Both views reject ultimate separateness, suggesting that all things are really part of a larger, connected whole – just as entangled particles act as if they’re one interconnected reality even across great distances.

Niels Bohr, one of the founders of quantum mechanics, introduced the idea of complementarity, which says that quantum entities can behave either like waves or like particles, but not both at the same time. What we see depends on how we measure. This goes against the usual ‘either/or’ of classical science, and instead accepts that complementary views are needed to understand the whole truth. In a similar way, the Samkhya school also talks about two basic complementary realities: matter and consciousness. Matter is ever-changing, while consciousness is still and eternal, and although they’re distinct, they work together to create our experience. So like wave and particle, matter and consciousness are different but both essential to the complete picture.

Quantum physics also brought the idea of probability into the heart of physical laws. Unlike classical physics, where we can in theory predict outcomes exactly, quantum physics equations only tells us the chances of different results. This is reminiscent of the Indian idea of the law of cause and effect – karma – in that here, everything isn’t fixed either, but rather, our past actions influence what’s likely to happen in the future. There’s room here for free will.

Many pioneers of quantum physics found inspiration in Indian philosophy. Erwin Schrödinger, for example, was deeply influenced by Advaita Vedanta. In What Is Life? (1944), he writes about the unity of all life, echoing the Vedantic idea that the self is the same as the universal. He believed that life is not separate from the universe, but one with it.

Shining from the Centre by Paul Gregory

Criticisms & Cautions

While the parallels between quantum physics and Indian philosophy are intellectually stimulating, scholars urge caution in drawing equivalences. One major concern is a possible category error when one mixes scientific constructs with metaphysical or spiritual doctrines. Quantum concepts like the wave function, superposition, or entanglement, arise from rigorous mathematical frameworks and empirical experimentation, whereas Indian metaphysical ideas are rooted in introspection and philosophical speculation. Additionally, quantum mechanics is open to multiple interpretations (such as the Copenhagen, Many-Worlds, and pilot-wave theories), not all of which assign a causal role to consciousness. Thus, equating consciousness-based interpretations of quantum theory with Vedantic notions of chaitanya may overstate the case for similarities.

There’s also a tendency toward romanticization – when for instance it’s claimed that ancient Indian sages anticipated quantum ideas. While Indian philosophy indeed presents profound insights into reality, such claims often lack empirical validation, and acting as if they do risks diminishing both disciplines.

Nevertheless, the conceptual resonances between these worldviews present fertile ground for cross-cultural and interdisciplinary dialogue, enriching both science and philosophy.

Toward a Unified Vision

The convergence of quantum physics and Indian philosophy we’ve considered does not suggest a literal equivalence between the two, but rather highlights overlaps in their shared exploration of the profound mystery of existence. Both disciplines challenge the classical notion of an objective, observer-independent reality, and elevate the role of the observer. Quantum mechanics, with its probabilistic framework, wave function collapse, and observer effect, reveals a universe that resists rigid physical determinism and demands a more nuanced, participatory understanding of reality. Similarly, Indian philosophical traditions such as Advaita Vedanta and Mahayana Buddhism emphasize that reality is not something out there, separate and static, but rather is intimately bound up with consciousness and perception. Moreover, the Upanishadic insight that ‘you are that’ (tat tvam asi) and the Buddhist idea of dependent origination, echo the quantum view of an interconnected, relational cosmos.

As Fritjof Capra observed in his 1975 book The Tao of Physics, the striking parallels between modern physics and Eastern mysticism arise from their common realization of the underlying unity of all phenomena. The implications of this convergence in perspective are profound. Science, often focused on objective measurement, benefits from a broader, more reflective, more philosophical lens on the context of its discoveries. Conversely, Indian philosophy gains a new dimension as its metaphysical insights find resonance with the findings of modern physics. Together they pave the way for a general holistic worldview – one that’s non-reductive, interconnected, integrative, and deeply participatory. Their comparison also invites a richer dialogue between science and spirituality, reason and reflection.

© Dr Punit Kumar and Dr Sanjeev Kumar Varshney 2025

Punit Kumar is Associate Professor of Physics at the University of Lucknow, and Sanjeev Kumar Varshney is a Delhi-based science communicator.