Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Obituary

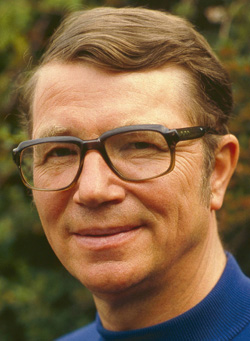

Colin Wilson (1931-2013)

Vaughan Rapatahana pays tribute to the positive-minded existentialist.

The passing of Colin Henry Wilson (June 26, 1931 – December 5, 2013) leaves a large rent in the fabric of authentic (meaning fully committed and lifelong intransigent) existentialist philosophy, a pretty spartan tartan at the best of times. As the Guardian obituary of 9th December 2013 lamented: “He was Britain’s first, and so far last, homegrown existentialist star.” Wilson was also a compelling harbinger of multifarious previously unheard-of authors, and an ever enthusiastic and immensely readable proselytizer of myriad divergent leftfield ideas. He was however first and foremost a philosopher, and he maintained that “I consider my life work that of a philosopher, and my purpose to create a new and optimistic existentialism.” The existentialist work The Outsider (1956) was his first and indeed his most famous book, and even if Wilson didn’t give full details as to how the positive existential state-of-mind he promoted was to be achieved, his ‘New Existentialism’ remains a lodestone in an increasingly bleak world peopled by the Dauphins of fundamentalist religions and the fundamentally anti-fundamentalist acolytes of Dawkins.

Wilson’s undoubtedly romantic impellent was to translate and codify his prime philosophic truth: that a person is greater than they think they are, and that, damn it, they should be doing something about evolving a lot faster – transmogrifying into the mighty being that they inherently are. In this doctrine he traveled far beyond the existentialist negativities of Sartre and Camus, as well as far beyond the trivialities of much academic philosophy. As such, Wilson also remained a lifelong counter to (post-)structuralist and postmodernist writers such as Derrida: for Colin Wilson, mankind is not a passive pebble rattling around inside imposed discourses; he is rather the master of his truly intentional conscious self. Wilson’s obsessive drive to relate everything to and from this profound inner nuclear warhead, his mystic overview of how things ‘really should be’, compelled him to write, transcribe, read, rave and produce prodigiously across two distinct centuries. Indeed he “exhilarated a generation with the bold possibilities of life” (Ken MacLeod, Aeon Magazine, 23 December, 2013).

Colin Wilson would accept the vast neutral materiality of the universe, but he would continue to maintain that man is pre-eminent: that it is the human transcendental ego which is the crux of existence, and not the external world. As he wrote: “And why are we here? In our moments of optimism and enthusiasm this is something we know instinctively. The purpose is to colonise this difficult and inhospitable realm of matter and to imbue it with the force of life… this world of matter is not our home. That lies behind us in another world. But for those with enough strength and imagination it will become our home. And when that happens the purpose of human existence will have been achieved” (Dreaming to Some Purpose, 2005). Similarly, in a 2003 online interview with Geoff Ward, Wilson proclaimed, “Our purpose in the world is eventually to enable spirit to conquer matter, to get into matter to such an extent that there is no longer any matter.” It is a vision of Man as Evolutionary Hero.

Forever the Outsider figure, transcending both the Anglo-American and Continental philosophical poles and immersed deeply among the tendrils of his own lavish ontological jungle, it is this – his preaching and teaching of our evolution into something natural yet supernatural – for which we will remember him. So as time fumbles forward, I believe this sui generis philosopher will continue to garner ever more glowing revisions from excavations of all his massive creative goldmine from libraries, second-hand bookstores, the web, and his wide-ranging presence also on videotape, audiotape and DVD. Why? Because Wilson is unique in his consistent and determinedly never-ceasing promotion of the realisation of human potential and growth via the self-augmentation of consciousness. He never wavered in this mission, ever.

It is apposite to say something about how Wilson viewed death, because he came to strongly affirm that bodily demise is not the end, but rather a passing to elsewhere. He writes: “It is not my purpose to try and convince anyone of the reality of life after death: only to draw attention to the impressive inner consistency of the evidence, and to point out that, in the light of that evidence, no one need feel ashamed of accepting the notion that human personality survives beyond bodily death” (Afterlife, 2000). Wilson also quoted Peter Fenwick on the belief that “Mind may exist outside the brain and may be better understood as a field, rather than just the actions of neurons in the brain” (Ward interview). This refers to the survival of a purely transcendent mind or intellect beyond any corporeal status. In this Wilson wants to transcend existentialist Martin Heidegger’s rather stoical appraisal of life as a flight towards death, stressing rather the drive toward far more life, the need for people to plunge more fully into the life-stream, as for example in his newly discovered and recently published essay from the 1970s, Evolutionary Humanism and the New Psychology (2013): “The threat of death – or any great emergency – has the power of unlocking the habit pattern of concentration upon objectives, and producing [an] overwhelming sense of ‘gratitude for existence’.” Here Wilson clearly points out how ‘traditional’ existentialism failed: it assumed suicide was somehow a freedom from responsibility, whereas in reality, suicide is merely bringing forward bodily death. Yet to Colin Wilson, by living one’s life to the fullest positive potential – by maturing one’s consciousness to the max – one may ultimately survive bodily demise as a fully-evolved conscious mind: “But I do feel, nevertheless, that life after death is basically true, that we don’t actually die… it seems to me it’s just a basic fact” (Ward interview).

© Dr Vaughan Rapatahana 2014

Vaughan Rapatahana has a PhD from the University of Auckland, is a published poet, and lives in Hong Kong.