Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Opera

Satyagraha

Grant Bartley focuses on the forces of history through Philip Glass’s opera about Gandhi.

Do great forces, or great men and women, make history? The theory of history promoted by Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) is that great people (for him, heroic men) determine the course of events. But is it rather the case that the course of social and cultural development is determined by implacable forces at work in society and culture en masse, as Hegel, Marx and others have maintained? I want us to consider this question with the help of Mahatma Gandhi, the English National Opera, and modern composer Philip Glass.

Gandhi Through Glass Symbolically

I recently saw Glass’s opera Satyagraha (1979) at the English National Opera near Leicester Square in London. Glass’s music might be familiar to you from the film Koyaanisqatsi (1982). His interacting melodic lines, based on sets of three notes, phase in and out of intensity in waves of varying turbulence, sometimes quiescent, and sometimes breaking out in frenetic refrains: his characteristic sound is the aural equivalent of water cascading along a river in swirls and eddies. In Satyagraha, this orchestral tide provides the setting for vocals in Sanskrit, the language of the ancient Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, while epithets or proverbs from the Gita are projected high onto the wall in the background. I think Glass intends the flow of his music to emulate the rhythms of history, since the nature and effects of the flow of ideas through history is his subject in Satyagraha. He wants to show the interplay of cultural and social forces to which our lives dance, and how such forces can produce a great man like Gandhi.

The opera concerns only a slice of Gandhi’s life, while he was working as a lawyer in South Africa. Even this piece of Gandhi’s life is not presented in chronological order. Rather, the opera is structured to spotlight the symbolic or spiritual aspects of Gandhi’s struggle.

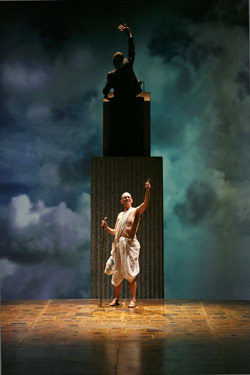

Gandhi confronting the spirits of popular opinion

ENO Satyagraha – ENO chorus, Alan Oke © Donald Cooper 2013

One of the motifs throughout the opera is that there are greater forces at work than are readily apparent in the details of life. Cultural and economic forces working on societies shape peoples’ experiences and influence their minds. Those minds then create ideas and policies which are applied to direct social and economic activities, be this everyday life, or riots and wars – and these physical conditions and events also feed back into culture, inevitably reshaping it. This feedback cycle is the motor driving history forward.

These social and cultural forces are represented in this production by giant paper or wicker puppets. At one point in the opera they are fighting each other, perhaps representing Indian and Western thought in conflict; at another point, giants made of newspaper represent the spirit of popular opinion. Everything in the production is symbolic of the wider meaning of what’s happening, from the sets, to the costumes, to the music. Indeed the opera starts symbolically, with Gandhi lying prostate at the centre of the stage then arising as people in rags stir into life towards him from the background. These are the poor and dispossessed emerging into the light shed by Gandhi’s message. And the first Scene of the first Act evokes the battlefield where in the Bhagavad Gita King Arjuna receives moral instruction from Krishna. This is emblematic of Gandhi’s spiritual struggle, which in Satyagraha is at least twofold: the struggle within himself, to become who he needs to be to be an effective vehicle for justice; and the struggle for justice for Indians in South Africa – itself foreshadowing the future struggle of India for independence.

Gandhi was ultimately a catalyst for India’s achievement of independence, but it is significant that the opera is called Satyagraha not Gandhi. ‘Satyagraha’ is the name Gandhi gave to his technique of resistance to oppression, and it means ‘truth force’. (Although his method was non-violent protest, Gandhi didn’t want to call his technique anything as passive-sounding as ‘passive resistance’.) Indeed, truth does have force, since error or deception provide unsatisfactory and unstable bases for society, and false foundations must weaken when subjected to strong scrutiny. This can be seen repeatedly in historical struggles for freedom, from the exposing of the falsehoods upon which slavery was based, to consciousness-raising against the falsehoods justifying the denial of votes for women. It is Glass’s intention not simply to portray Gandhi, then, but to use his life to reflect on the working of the force of truth in social struggle. The following is my interpretation of the director’s interpretation of Philip Glass’s interpretation of the life of Gandhi. Interpret it as you wish!

A Medium For Truth

The three Acts of this opera are called ‘Tolstoy’, ‘Tagore’ and ‘King’. Leo Tolstoy, the poet Rabindranath Tagore, and Martin Luther King, Jr, represent for Glass the past, present and future – at least from Gandhi’s perspective – of truth force. Indeed, they each appear in the background throughout their respective Acts.

After setting up the key meaning of the piece with regards to the spiritual battle that Gandhi’s struggle is presented to be, we are taken to Tolstoy Farm in South Africa. Tolstoy Farm was an idealistic community founded by Gandhi near Johannesburg. Here, from 1910 on, he nurtured his policy of peaceful resistance. The name of the farm shows the influence on Gandhi of the man whom Glass credits with the past of satyagraha. The scene is one of sowing and harvesting, simultaneously symbolising the nobility of peasant life, which Tolstoy is famous for championing, and the harvest of Gandhi’s ideas that is to come.

Gandhi lighting the flames of change

ENO Satyagraha – Alan Oke, ENO chorus © Donald Cooper 2013

For Glass the farm is also where Gandhi gains his resilience of purpose. One projected quote is, “The world is not for the doubting man,” and generally the quotes here concern purification of thought, for it is at Tolstoy Farm that Gandhi develops and consolidates his ethical thinking: that what matters is the benefit of the masses. Here, as Gandhi starts to hear the voice of the people, he shuns his Western clothes, this symbolising his shunning of Western assumptions. This is followed by a similar mass reclothing of the people around him. Then, visually and aurally, the people become united, grouped together with a unified voice, as if to say that the power of the truth is focused when the people speak with one voice, through one man. This represents a protest against South African legislation repressing Indians living there.

In Act II, ‘Tagore’, at first we step back in time to 1896, to see people in Western (colonialist) garb waiting for Gandhi. The music speeds up to keep pace with the mob anger at his campaigning for Indian rights, as in the background, giant newspaper puppets incarnate the powers of the press and giants of business. Gandhi is generally rejected by Western opinion. To 1906: newspaper flows, indicating that Indian opinion is changing. Indian Opinion was also the name of Gandhi’s South African newspaper publicising satyagrahan principles. Thence to 1908, where Gandhi is among the people, who come out with lamps, wearing white, symbolic of purification. Gandhi bears a torch, and upon his example Indians throw the certificates of registration that entitle them to live in South Africa into a cauldron in the middle of the stage. Gandhi sets them alight, also symbolising lighting the fire of revolution.

Among other things, Act III represents the future of the truth-struggle. Throughout an enactment in the foreground of a march led by Gandhi in 1913 in sympathy with oppressed South African miners, Martin Luther King Jr is in the background giving his ‘I Have A Dream’ speech. (Many great lives seem to involve marches, curiously.)

We know that Gandhi and King both succeeded in their goals, at the cost of their lives. But here King symbolises the future of the force of truth as it continues to carve a path into freedom for humanity. Through this juxtaposing of Gandhi with King, Glass represents the peaceful but forceful insistence on the truth as a means of change as Gandhi’s greatest legacy to humanity.

At the end of the opera, Gandhi first symbolically looks up at King; then he preaches to the poor concerning the continuing power of truth – this seeming to imply to the watching audience the question, ‘What does the force of truth need to challenge in our present and future?’ Indeed, one might be inspired to ask, ‘What does history demand of me?’ So I’d say that the ultimate message of Satyagraha is that the future is in your hands.

The Force of History

What then can this slice of the life of Gandhi tell us about the link between the forces and the people that make history?

Like the flow of a river or of Glass’s music, at any place and time in history the interacting flow of ideas and events can be placid or turbulent, according to what combinations of social, economic and cultural factors are operating then and there. But we need to recognise that the forces working through culture and society to refashion them, are psychological forces, insofar as they operate through human experiences and shape human desires. As illustrated perfectly by this opera, these forces can therefore operate on the mind of the right individual to make them into an effective visionary leader, a shaker of foundations – what is called a ‘great man’ or a ‘great woman’. The basic pattern is that great people emerge in times of historic turbulence, and are refined by the stresses created by this turbulence to catalyse the change that the turbulence itself demonstrates is needed. It’s a cultural evolutionary response to the needs of the circumstances, if you like.

Gandhi and King

ENO Satyagraha – Alan Oke, Member of Skills Ensemble © Donald Cooper 2013

By ‘historic turbulence’, I mean the swirling together of ideas and events to create a sustained period of troubles. These troubles continuing, even intensifying, then provoke awareness of the underlying problems of culture or society that have created them, by opposing crucial truths that sensitive people will be becoming aware of. Some particular person’s peculiar moral sensitivity also means that they retain the moral indignation through which they can, in the face of many obstacles, develop the resolution needed to refine and achieve a vision for change. They need a combination of sensitivity and obstinacy in order to be the right person for the job.

So sticking with the turbulence metaphor, the template for the development of a great person is that their experiences within turbulent events awaken them to the falsehood at the centre of and driving the turmoil, and the urgency for change that this represents. The continuing crisis throws this need for change into ever sharper relief, until the sensitive yet obstinate person is forced to an understanding through which they can bring about the change that starts to solve the problem. One could say that the social, economic and cultural forces of human life create circumstances that squeeze great people out like an Invisible Hand squeezing clay out of a giant tube. So it is neither great people alone, nor historical forces alone that determine the flow of history. Rather, the forces create the conditions by which a person is made or forced into greatness, and that person then in turn alters those conditions. In other words, the forces of history create the people who create history.

I think this is a general pattern for the emergence of great historical figures, including Martin Luther King Jr and Nelson Mandela, for example. This template is portrayed excellently in Satyagraha, where Glass shows social and cultural pressures starting to make Gandhi into a ‘great soul’ (the meaning of his title ‘Mahatma’). In Satyagraha, the turbulence is the struggle of the Indians for justice in South Africa. As they resist official injustice, repression grows harsher, and Gandhi – sensitive to injustice to the extent of becoming a lawyer – is forced to refine his understanding of how to combat it.

As Glass interprets it, Gandhi is led to seek a self-purification whereby he detaches himself from the fears, selfish desires and petty grievances which alienate us from each other. They’re mundane distractions from his higher purpose, which will eventually mature into the ideal of Indian emancipation. In this Glass represents Gandhi as a medium for the truth that’s discovered by turning away from materialism and status-seeking: the truth that these are false goals, or at best merely shallow ones. And for Glass, the deep goal of Gandhi’s purification is to facilitate a love for people through a love of God (Krishna or Brahma). Through this love, where according to a quote on the wall from the Bhagavad Gita, enemy and friend are seen as alike, Gandhi’s will can act purely, through his love of the people. And by this, Gandhi can become a vessel which can receive, then retransmit, and thereby accomplish, the needs of the people. Poetically put, in emptying himself of himself, the man becomes the people, and so may the people become the man. Then may the people be united in and ignited by the flame of the purified vision of the man.

The purification of his mind is vital, for it is only by Gandhi’s freeing himself from the static of everyday thought that he can see his history-changing vision clearly. His gaining of resilience through the stresses from the forces of history is just as important, since only through endurance can a great person achieve their great purpose. As well illustrated even in Satyagraha’s small cross-section of Gandhi’s life, the achievement of any profound social or cultural progress is beset with obstacles, due mainly to the inertia of vested interests. The powerful establishment like things as they are, and those for whom any change is loss will always try to prevent a social or cultural paradigm shift. This is another principle of radical historical change. It’s demonstrated here by Gandhi being vilified by the press, set upon by mobs, and frequently imprisoned by the (British) South African authorities. Gandhi’s potential to be a great man comes to fruition only because this continued opposition does not weaken his attachment to truth and justice, but instead consolidates his resolve and clarifies his vision, increasing and sharpening its force.

The Work of Art

Satyagraha is sung entirely in Sanskrit, and Glass does not allow translations to be displayed during the performance, claiming that the pure sound is enough to convey the force of the drama. On paper this might appear to be overly indulging the artist, but I found him to be correct: the fact that I didn’t understand the words didn’t detract from the experience. Or, never mind the semantics, feel the symbolism!

Either universality or profundity of subject matter are necessary for art to be great. Glass’s opera surely has both. Yet in the final assessment of any work of art, the effect is all: its value must be judged in the strength of its emotional and intellectual impact upon its audience. Satyagraha stimulates an imagining of possibilities concerning the sweep of history – what more profound effect could a work of art have? Congratulations then to Philip Glass for creating a work of such depth and breadth of vision, and to the English National Opera for presenting it so powerfully and beautifully.

There is a motto above the entrance to the Victoria and Albert Museum, a museum of design in London: “The excellence of every art must consist in the complete accomplishment of its purpose” (Sir Joshua Reynolds). As an expression of the force of truth, I’d say that the ENO’s production of Satyagraha accomplished its purpose forcefully. As for my opening question, ‘Do great forces, or great men and women, make history?’ – this question presents as false a dichotomy as the question, ‘Do great artists, or great subject matters, create great art?’

© Grant Bartley 2014

Grant Bartley is an Editor of Philosophy Now. His book considering revolutions through history, The Metarevolution, is available through Amazon. It may be sampled by clicking the About link on the Philosophy Now homepage.