Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

William James (1842-1910)

Alistair MacFarlane takes a pragmatic look at the life of an American genius.

William James was America’s greatest psychologist, and became one of its great philosophers. In The Principles of Psychology (1890) he investigated consciousness, sensation and perception, memory, thought, emotion, attention, will, space, time and knowledge. In his studies of how we perceive time, James examined what he called ‘the specious present’: how conscious experience slips into the past whilst also yielding to an emerging future. He coined the term ‘stream of consciousness’, and famously described the stream of consciousness experienced by a new-born baby before the formation of any ability to conceptualise or make rational decisions as a “blooming, buzzing confusion.” After a study of religions in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) he produced a third masterpiece, Pragmatism (1907). His creation of major works in three different fields, each of lasting influence, is a unique achievement.

Early Life & Marriage

William James was born on 11th January 1842 in New York City, to Henry James Sr. and Mary James (née Walsh). His paternal grandfather, also named William James, came from Ireland in 1790 and amassed some three million dollars from business dealings in upstate New York. The elder William James was a devout and strong-willed Presbyterian; but when his son Henry (the philosopher’s father) embraced religion, it was of a very different sort. Henry had discovered the teachings of the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, and developed from them his own idiosyncratic form of religion. As a result his father renounced him; but Henry successfully contested the will, and so secured his inheritance. This allowed him the freedom to proselytise his beliefs, and he became well-known in New York intellectual circles. Hence the younger William James was born into a wealthy family with stormy relationships, an intense religious atmosphere, and wide intellectual connections. He had three younger brothers, Henry, Garth, and Robertson, and a younger sister, Alice. His brother Henry James, the famous novelist, immortalised the family home in his work Washington Square (1881). All the James children were educated at home by tutors. The lack of systematic education was compensated by a lively intellectual atmosphere and regular trips to Europe. On one visit to England, the young William met Thomas Carlyle, Alfred Lord Tennyson and John Stuart Mill.

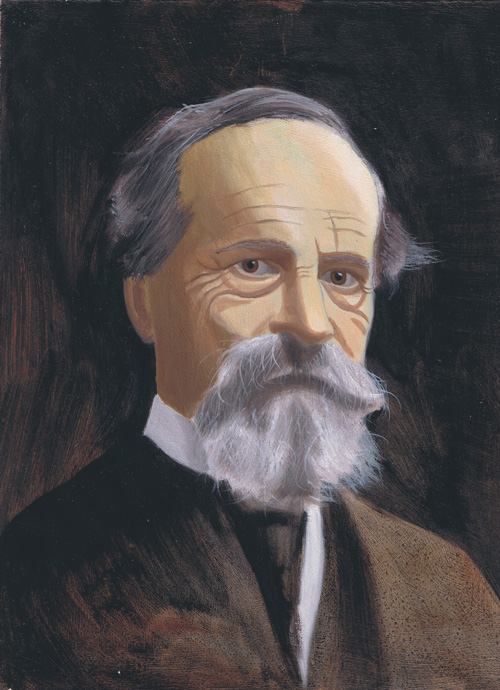

Portrait of William James © Darren McAndrew 2014

William James was a difficult man to live with. He was subject to severe depressions, and had problems with his eyes, back, digestion and breathing, which were exacerbated by a bad temper, moodiness, boredom and fatigue. His marriage in 1878 to Alice Howe Gibbens may well have saved his life, as he later acknowledged. After marriage his health improved greatly, and Alice’s calm practicality provided the order in his life he so greatly needed. They had four sons and one daughter, one son dying in infancy.

From Medicine To Psychology

William was precocious, highly intelligent, aware that he had no need to earn a living, yet very competitive with brother Henry and determined to seek distinction. Showing some skill in drawing, he first studied painting as a pupil of the well-known artist William Hunt, but soon abandoned hopes of an artistic career. However, it’s clear that he had a well-developed artistic sensibility, and his later writings show an emotional sensitivity and a gift for metaphor and picturesque description. It was equally clear that he sought a greater distinction than he felt his artistic gifts could guarantee. In the end he choose to study medicine, enrolling in 1861 in the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard to study chemistry and comparative anatomy.

James then entered Harvard Medical School in 1864, but, under no pressure to qualify in order to practice, and still unsure of what he really wanted to become, he interrupted his medical studies twice. In 1865 he joined the famous Harvard biologist Louis Agassiz on an expedition to the Amazon to collect specimens for a new zoological museum. After resuming his studies he took another break, partly because of ill health and partly because he wanted to study in Europe. He finally completed his medical degree in 1869, but never practiced medicine, having neither need nor inclination to do so. Yet James was far from being a dilettante – rather, he was the opposite; a man diligently seeking his true vocation, and in the process becoming a polymath.

He began to see a way forward, and in 1873 chose to accept a position as an instructor in physiology and anatomy at Harvard. James had become deeply interested in what he called ‘physiological psychology’ – the issue of how creatures of flesh and blood could relate to the spiritual world of their experiences, beliefs and culture. From that point on his intellectual interests began to cohere, and his intellectual horizons continually expanded, resulting in the publication of his masterwork on psychology in 1890. His deep and abiding interest in people – what they did, what prompted their actions, how they reasoned, and how they related to one another – had two major consequences. It meant he shifted emphasis in the emerging discipline of psychology from the theoretical to the practical; and it meant he sought a new form of philosophy that was based on human beings rather than on depersonalised metaphysical abstractions.

Pragmatism

With his deep knowledge of psychology and his wide spread of interests, James and Pragmatism were made for each other. Pragmatism is a philosophical approach that puts people at its heart, and so had an immediate appeal to one of the founders of modern psychology. He did not create Pragmatism, but he thoroughly embraced it.

Pragmatism sees truth as made by human beings rather than found by them. James’ version of Pragmatism accepted the role of hard facts, but insisted that facts have both human and independent material aspects. Truth in James’ version of Pragmatism consisted of useful ideas. He saw the utility of ideas both in terms of giving a power to predict based on experience, and also in terms of their relevance to human behaviour, especially in encouraging the development of valuable emotions. His naturalistic approach to knowledge enormously influenced the development of Husserlian Phenomenology and its later offshoots. In fact, many of the major themes in current philosophy can be traced back directly to his work.

The Pragmatist school started with Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), but was adopted and taken in a new direction by James. James’ contribution, as expressed in Pragmatism, was vital, despite Peirce’s fury at what he saw as an inaccurate representation of his original work. Yet James was scrupulous in acknowledging Peirce’s priority and originality – to the dismay of James’ family, who believed that he deserved more credit than he claimed. In retrospect it is clear that Peirce and James had very different approaches, whose effects in the development of Pragmatism both still persist. The two approaches were eventually unified into a coherent discourse by John Dewey (1859-1952).

Last Days

James fought ill health all his life. Despite this he managed to pursue a dual career, becoming a prolific popular writer and speaker whilst making fundamentally important contributions to psychology and philosophy. James became a much loved teacher, and brought great distinction to Harvard, not only because of his originality and brilliance, but also because of his great openness of mind and generosity of spirit. After Pragmatism was published in 1907, his health deteriorated seriously, and he resigned from Harvard in 1910. His last public engagement was to deliver the Hibbert Lectures in Oxford over 1909-1910 – published as A Pluralistic Universe in 1910. James died of heart failure on August 26, 1910 at his summer home in Chocuroa, New Hampshire, and was buried in the family plot in Cambridge Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Using his knowledge of physiology and psychology, James brought a wholly new and fresh approach to philosophy. He rejected both scientific realism (the idea that the scientific model of the world is not just a model, but how the world really is) and absolute idealism (the idea that the world is only mental in nature) because in different ways they both refused to address the legitimacy of important humanistic, religious, moral and metaphysical claims.

James wrote, and spoke, in a vivid, attention-grabbing style that enthralled interested members of the general public but infuriated an emerging band of professional philosophers. The effect of James’ free and easy forms of argument on this latter class was memorably described by Bertrand Russell when he reviewed Pragmatism for the Albany Review of January 1908, under the heading ‘Transatlantic “Truth”’. Of James’ argument for Pragmatism, Russell said, “It is insinuating, gradual, imperceptible; it is like a bath with hot water running in so slowly that you don’t know when to scream.” Other professional philosophers have been arguing against the Pragmatic concept of truth ever since. But James saw that truth as a whole must encompass human as well as physical realities.

© Sir Alistair MacFarlane 2014

Sir Alistair MacFarlane is a former Vice-President of the Royal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor.