Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

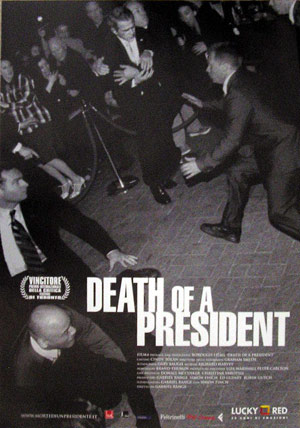

Death of a President

Terri Murray finds herself in a maze of mirrors, but has Jean Baudrillard as her guide.

Directed by Gabriel Range, Death of a President is a 2006 British mockumentary about the assassination of George W. Bush. By deploying all the formal conventions and stylistic techniques of television news and documentary, including interviews with ‘experts’ (played by actors) and archival footage (taken from unrelated events and then woven together into a cohesive tapestry), this film persuasively convinces the viewer of its content. So thorough is the mimesis that even the most confident viewer begins to doubt his own knowledge of historical events. It is not until over halfway through the film, when Dubya’s assassination unfolds on screen, that the viewer’s own background knowledge jars with what he is seeing. He only begins to question the veracity of the other ‘facts’ presented in Death of a President because of his (near) certainty that George W. Bush was not actually assassinated. The film achieves this merely by mimicking the formal conventions of factual reporting.

Images from Death of a President © Optimum Releasing/Newmarket Films 2006

Death of a President serves as an ideal illustration of what French postmodernist philosopher and cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) called simulation. Baudrillard used this term in a dazzling variety of contexts, but he seems to mean by it the multiple ways in which contemporary life is characterised by, and inseparable from, representations, images, symbols and reproductions. As such, we can only experience the world through the filter of the prefabricated concepts and expectations produced by our media-saturated regime. Consider trying to visit New York City without your experience being shaped by preconceived ideas taken from movies and television. Or try going on a date without your experience being coloured in some way by ideas of romance or ‘the perfect date’ borrowed from pop culture, TV, or movies. Try looking in the mirror and assessing your own body without reference to a magazine advertisement, film or television character.

Reality Refocused

You do not have to wire your head to a video game 24/7 to be immersed in simulation. Baudrillard regards simulation as a ubiquitous social condition. It is no longer restricted to television or some other electronic medium. Rather, the principle of simulation now fundamentally orders all of social life in the developed world.

A basic idea we can take from Baudrillard’s works is that as a result of our culture’s total immersion in images and other representations, we now generally experience reality distorted and at a distance. In a paper he gave at the University of Sydney in 1987, and also published as The Evil Demon of Images (1988), Baudrillard claimed that while we think of images as principally referring to a real world, “none of this is true… images precede the real to the extent that they invert the causal and logical order of the real and its reproduction” (p.13). Although the common understanding is that a simulation is a fake or inauthentic version of something real, Baudrillard is suggesting that the simulation can no longer be clearly distinguished from the truth. For Baudrillard, the distinction between simulation and reality has broken down irrevocably, such that we can no longer view them as opposites. In a culture obsessed by images and consumed by frantic self-reference, there is no essential, pure, unmediated reality left. There is no backdrop of ‘truth’ against which we can measure the authenticity of a representation.

As we become aware of the fact that nothing is outside the encompassing flow of images and other simulations, we panic. In an anxious attempt to reclaim reality, we make a fetish of the supposedly authentic, to the extent of creating “glass dishes with tiny bubbles and imperfections: proof they were crafted by the honest, simple, hard-working peoples of … wherever,” as Ed Norton’s sardonic narrator explains in Fight Club. But attempts to recreate the feel of reality are themselves simulations. Going back to the example of looking in a mirror, even the little voice in your head that says “embrace the extra pounds” probably came from Facebook, a song, or a self-help book that entreated you to ‘embrace yourself’, ‘be yourself’, or ‘unlock the real you’. These are examples of what Baudrillard calls the hyperreal – authenticity as yet another simulation. For Baudrillard, the notion of originality has been rendered obsolete. The very notion of a ‘reality’ – something more authentic than this, having some kind of premeditated existence – is seen as naïve and quaint. Most media nowadays takes for granted that we live in a media-engulfed world where intertextual references are commonplace and we get most of the references. As such, the need to refer to anything outside of media culture almost disappears.

Baudrillard sees the world in which we live as one in which representations have been cut loose from, and operate independently of, history, facts or reality. He seems to draw this idea in part from Umberto Eco, who remarked upon the total self-absorption of the media in his short 1984 essay A Guide to the Neo-Television of the 1980s. Eco observed that in the era of Neo-TV, it matters very little whether what is on TV actually refers to anything beyond the fact of televisual appearance itself. Just being on TV makes something remarkable or newsworthy; makes it count as ‘news’ or ‘current affairs’. The medium literally is the message as well as the messenger. So the media have the power to make history, by selecting what counts as an ‘event’ and talking about it in ways that have become standardised through wide circulation.

Reality Rewritten

Although the simulations now float free from any necessary reference to some natural, ‘pure’, or unmediated realm of existence, Baudrillard also regards them as, ironically, nevertheless a part of our actual lives, in that they have real effects. Far from being relegated to an isolated, artificial nether realm, they have a deep connection with our behaviour. This turns the conventional thinking about the relationship between the real and the image upside down, or as Baudrillard says, ‘inverts’ it. Instead of our representations being derived from reality, now they precede and produce it. In other words, reality becomes an effect of representation. In The Evil Demon of Images Baudrillard calls this an implosion of image into reality.

A striking example is plastic surgery. The images of beauty presented by the media have already created a world in which people imitate the image, and as more and more of them do this, what was perceived as ‘real beauty’ becomes ever more insidiously defined by the surgeon’s knife or the Photoshop artist.

As images increasingly intersect with experience, it becomes increasingly doubtful that there is any aspect of reality that is not simulated. Think, for example, about how pornography supposedly rewires the brain, making (so-called) real sex less appealing and even impossible for some porn addicts. However, isn’t it the case that now ‘real sex’ just is whatever kind of porn-affected sex people are actually having in our pornographic age, regardless of whether it resembles some now merely abstract idea about what healthy sex ‘should’ be?

In this free-floating context, it matters not whether words are used accurately. The regime of representations has its own language that operates independently of etymology or dictionary definitions, and usurps the literal definitions, reshaping them to new agendas. For example, the word ‘feminism’ has acquired a range of negative and blatantly false connotations, such as the idea that feminists are anti-male, or that men cannot be feminists. But the true understanding matters little, since people only hear or see the connotations. The literal meaning of ‘feminism’ has simply lost all currency. Meanwhile, Catharine MacKinnon and others have pointed out how the ubiquity of pornography, with its humiliating representations of women as sexual objects, obstructs gender equality and freedom of speech in the real world (if such a thing can really be said to exist). Her argument is that women no longer have an equal ability to express themselves, since in a world saturated with porn, nothing they say can be taken seriously. Likewise, try using the word ‘terrorism’ to refer to the way the United States has used covert CIA ops to force its free market policies on South America, Central America, South East Asia, or anywhere else. It has become impossible for ‘terrorism’ to be used with a western democratic referent.

A Significant Inversion of Reality

Emblematic of this mediated self-referential world we now inhabit, was the Neocons’ peddling of fraudulent and thoroughly discredited claims to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The truth didn’t matter. The fact that Iraq had no WMDs had ceased to matter. What mattered was what was said in the media by people in apparent authority.

In a January 2003 State of the Union address, President Bush declared, “The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” Joseph Wilson, former Deputy Chief of Mission to Iraq had already shown this to be false. Secretary of State Colin Powell, chosen for his popular ‘credibility’, gave a spectacular seventy-five minute performance at the United Nations (which he later described as a low point in his career). Here, supported by an array of props, including a small vial of anthrax-simulating powder to illustrate how little would be required to cause a massive loss of life, he assured the delegates, “These are not assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence.” Many of his claims had already been rejected both by the intelligence community and UN inspectors, but it didn’t matter. Despite the fact that WMDs never materialized, the Washington Post described Powell’s evidence as “irrefutable”. However, when at great personal risk a brave British intelligence officer, Katherine Gun, exposed an illegal NSA operation to spy on and pressure UN delegates to support the war measure, the US media ignored the revelation. Gun’s exposé didn’t fit with the foregone conclusion that military invasion was necessary, so it wasn’t news. The decision to invade had already been made. The US media abandoned any attempt at objectivity, and celebrated the militarists while silencing the critics. TV station MSNBC (owned by General Electric, which profited from the war), cancelled Phil Donahue’s talk show Donahue three weeks before the invasion because he presented too many anti-war guests. CNN, Fox and NBC all fell into step, presenting a succession of retired generals as analysts who could be counted on to convey administration themes and messages, especially as all had been given Pentagon talking points, and especially as virtually all of them worked for military contractors who would profit from the war. Internal Pentagon documents referred to them as “message force multipliers” who would inject the public with the Pentagon’s ideas and present these ideas to Americans “in the form of their own opinions.” (See The Untold History of the United States, Oliver Stone & Peter Kuznick, 2012.)

The point is that the media’s definition of these events was enclosed and separate from anything happening in any world that might be thought of as existing apart from its images and representations. It was by reference to other media images that each image was generated. All of the references were intertextual, and designated nothing outside of the media-enclosed system of images. But they were believed.

Art Imitating Reality Imitating Art

Both in its form and in its content, Death of a President sets out to demonstrate the blurring of the line between images and reality. It does so first by using the TV documentary format, thereby revealing that content no longer holds sway, since now form determines the perceived ‘truth’ of the material presented. So accustomed are we to accepting at face value the ‘facts’ presented through this format, that we respond more to our own expectations of the genre than to anything in its content.

Secondly, as its story about the manhunt for the President’s assassin unfolds, and we watch how this descends into prejudice, with the authorities fingering an innocent Syrian man for the crime and then railroading him to a seemingly inevitable conviction, we realise that Death of a President is also about the very real consequences of this post-reality world. FBI agents blatantly contradict themselves, and later ignore mounting evidence that the actual perpetrator was a disaffected US Army veteran who blamed Bush for the death of his son in the Iraq War. But none of this matters: the Vice President has political reasons for wanting the assassin to be a Syrian, and so he shall be. Syrian ‘experts’ are brought in as analysts on news-styled chat shows, and it doesn’t matter that they’ve been discredited or have personal agendas. Their message prevails merely because it is louder and it’s on TV.

The movie’s ambition is to make viewers understand the real implications of their unquestioning acceptance of our thoroughly mediated world. Its closing titles, still very much in documentary mode, claim that the assassination led to the ‘USA Patriot Act III’ which “granted investigators unprecedented powers of detention and surveillance.” While the ‘III’ is fictional, the USA Patriot Act of 2001 had in fact already enacted strikingly similar powers and taken away many civil liberties and protections Americans had previously taken for granted. The film simply mimics the means by which this was accomplished, reminding the viewer that it could easily happen again.

© Dr Terri Murray 2015

Terri Murray is a graduate of New York University’s Film School. She has taught Film Studies at Hampstead College of Fine Arts & Humanities in London since 2002, and is author of Feminist Film Studies: A Guide for Teachers (2007).