Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Dominant Narratives of Future Societies

Ernest Dempsey on what sci fi stories say about the stories controlling our lives.

Curiosity is instinctive to life-forms with complex nervous systems. Humans, for example, tend to quest for knowledge. One of the fruits of knowledge is technology, the practical application of knowledge to satisfy various needs. Yet technology influences human society not only materially, but also culturally and existentially, and as it transforms society it raises a number of challenges. For instance, just as different groups – geographical, racial, or cultural – sometimes clash over the control of natural resources, people also tend to experience similar conflict over control of advanced technology. Science fiction novels such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), and many others, illustrate a recognizable pattern in advanced scientific societies: that those who control the technological resources define the dominant narrative. A ‘dominant narrative’ is a set of stories that dominate a culture and to a large extent define reality for its members. In the societies both of Brave New World and of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? the dominant narrative is determined by the class who possess the technological power, particularily the power to intimidate and to force dissidents into submission.

Worlds Gone Bad

Cover of Brave New World © Bantam Press

Brave New World depicts a dystopic world in the Twenty-Sixth Century when a single World State is the main political entity. It controls artificial reproduction to the degree that natural birth through mothers and fathers is but a story from the past. Instead of elementary schooling, children are indoctrinated in their sleep via advanced ‘hypnopaedic’ educational technology. To fit them ‘perfectly’ (or so they are assured) for the work roles to which they will be assigned, they are divided genetically and educationally into a rigid hierarchy of classes. Recreational sex is encouraged, but it is utterly removed from its reproductive role and its emotional role in forming enduring relationships, which are frowned upon. Thus the owners of the technology completely control the social hierarchy by manipulating peoples’ genes as well as their opinions and feelings.

This scenario is most likely to strike us as abhorrent. However, our judgment of the society of Brave New World comes from within our dominant narrative. Do we have a neutral place to stand, from which we can fairly judge and assess different societies?

Cover of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? © Panther Science Fiction

Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – made into the film Blade Runner (1982) – also presents a future dystopic world. Here a world war has destroyed much of the environment, and humans have started to migrate from Earth to off-world colonies. The story is set in a run-down Los Angeles where there are flying cars and people can control their own moods using a ‘mood organ’. Technology corporations have developed highly intelligent androids that have assisted humans in colonizing other planets, the pinnacle being the Nexus-6 robots. But some of the androids have self-consciousness and have refused to live in slavery. A group of Nexus-6 kill their human masters on Mars and flee to Earth. Here, bounty hunter Rick Deckard is assigned the task of tracking and killing the six androids remaining at large.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? presents a deep ethical conflict: Deckard is essentially a killer for money. He doesn’t feel bad about it until he starts questioning the distinction between humans and androids that is the basis for the justification of hunting down the androids. The distinction is part of the dominant narrative of his society, which says that androids lack empathy and can be dangerous, and so can be killed without scruple. On the face of it, this justification sounds valid, but questioning the dominant narrative quickly undermines the justification for the killings and other social facts. For instance, if humans have empathy, why do they kill? Is dividing into social classes (or castes) and subjecting the lower classes into near-slavery justifiable? The character of John Isidore is a great example here – he’s been nicknamed ‘chickenhead’ because he cannot pass a certain intelligence test, and is therefore put into a lower status class and made to work bad jobs and endure poor living conditions, even though he is more capable of empathy than members of the ruling class.

Another interesting aspect of both dystopic worlds is the presence of a religion followed by the masses but actually defined and promoted by the owners of the technology. In Brave New World, Henry Ford (of Model-T fame) is the major religious figure idolized by the masses, whom the state encourages them to believe in and look up to as a prophet of the perfectibility of life through technology. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Mercer is a prophetic figure who can be accessed using the technology owned by the state. Both figures play a key role in maintaining the dominant narrative of their respective societies.

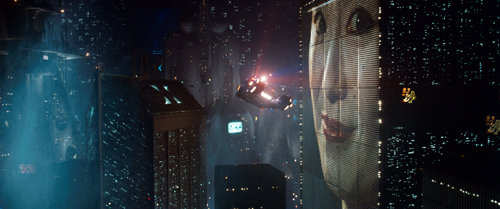

The world of Blade Runner

The Power of Counter-Narratives

As is well-known in sociology, in any society there is often at least one counter-narrative to the dominant narrative – a story that claims that reality is different, or even quite the opposite, to what the dominant narrative claims it to be. Such counter-narratives are followed by small groups of individuals that have different cultural or historical backgrounds, or who are cognitively different, from the mainstream. Brave New World and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? both present interesting counter-narratives. In Brave New World, the character John (the ‘Savage’) is a personification of a counter-narrative. Born on a reservation away from the influence of the World State, through a natural birthing process – from a mother and a father – he is brought like a freakshow curiosity back to ‘civilization’. He is disliked and rejected by the state controlling the means of (mis)information, but he at least gets a handful of followers, such as Bernard, who use him to challenge the political authority. Rather than Fordism, John has learned his values from a tattered old copy of Shakespeare’s collected plays, which is the source defining reality for him. And in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Buster Friendly presents the counter-narrative. A radio/TV anchor, Buster mocks the technologically-defined religion of Mercer and its followers; and he himself is followed by a minority who have deviated from the dominant narrative, including John Isidore.

Android Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) has a final moment of empathy in Blade Runner

Stills from Blade Runner © Warner Bros 1982

Sceptics may wonder what we can learn from these books given that they are works of fiction; after all, the societies they portray don’t even exist. However, they have value in two ways. Firstly, they identify and critique certain nascent tendencies in our own society. The technique is a little like the philosophical manoeuvre known as reductio ad absurdum: the tendencies are extrapolated to their logical conclusion, which is then shown to be unappetising. Secondly the stories allow us to examine in general terms how dominant narratives work and are sustained, and to do so much more easily than if we were to look at those of our own society. It is never easy to step outside your own world’s narrative and see it from the outside.

Brave New World and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? are works of deep social and philosophical implication. They both consider the issue of the defining criteria of reality. The relation between technology and dominant cultural narratives is a point of concern because after all, technology is a part of our lives too. However, shall we allow a part of life to define the whole of reality for us? Or should we listen to, perhaps even actively look for, other narratives, whereby we may get a different picture of reality? Works like Brave New World and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? provide us with starting points to encourage us to ask brave new questions.

© Ernest Dempsey 2015

Writer and editor Ernest Dempsey has authored five books. He is the chief editor of the quarterly Recovering the Self (recoveringself.com). He runs a popular blog Word Matters! (ernestdempsey.com).