Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Tinker Thinkers by Susan Gardner & Amy Leask

Jana Mohr Lone teaches children to argue.

Adults tend to think of children arguing as something negative, because in this context arguments are generally understood to involve fighting, quarreling, anger, frustration, and tears. Philosophers, however, understand argument to involve reasons, not rancor. As students learn in virtually any introductory philosophy class, arguments are attempts to persuade other people of the truth of particular claims based on the reasons offered for them.

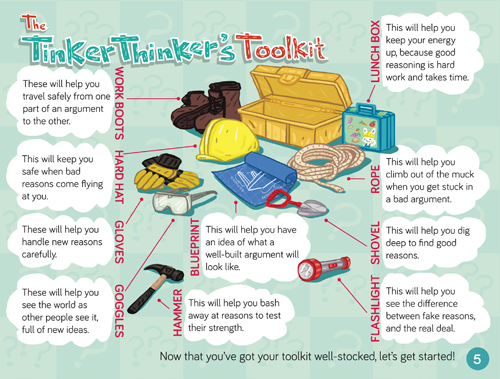

In their book Tinker Thinkers (2014), Susan Gardner and Amy Leask, with the help of illustrator Ami Moore, encourage children to argue: that is, to express their views and give good reasons for them, and also to evaluate the reasons other people offer for their beliefs and actions. Geared to elementary school age children, the book’s central metaphor is a construction kit that contains various tools required for building strong intellectual structures. For instance, Tinker Thinkers advocates the frequent use of the question, ‘Why?’:

“When you ask WHY, you are looking for reasons! You need to know what the reasons are for thinking or doing anything. That way you can see if a strong argument can be built out of them.”

Strong arguments require good reasoning, the book explains, and it sets out to involve children in learning about the parts of an argument and some of the ways reasons can be evaluated. To do so the book engages children in a variety of activities about, for example, what constitutes a good reason and how to identify what particular claim is being made.

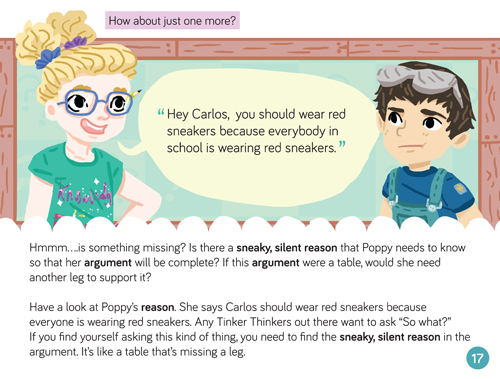

One of the exercises invites children to color in the conclusions of various arguments, noting that reasons don’t always appear before conclusions (“You should love your dog because dogs are always so loyal.”) Remarking that sometimes people don’t articulate all of the reasons needed to support a claim, the book observes that certain reasons are “sneaky and silent” like a table missing a leg, and require some thinking to discover, and an exercise asks children to circle the “sneaky silent reason” behind various arguments (“You should buy me a video game because I want it.” Is the sneaky silent reason (a) You should buy me whatever I want, or (b) Video games are fun?). Another activity involves testing whether the reasons given are sufficiently powerful to support the argument being made. The ‘counterexample hammer’ gives children a means to investigate the strength of their reasons. So in the video game example above, kids would imagine a situation in which a parent should not buy the child whatever he or she wants: What if the child wants a loaded gun? And the authors point out that if you can’t think of a counterexample, you might have a pretty good argument.

Some pages from Tinker Thinkers

Tinker Thinkers illustrations © Ami Moore 2015. Please visit tinkerthinkerkids.com

Reasons For Reasons

What matters, Tinker Thinkers declares, is not what people tell you to do, but the reasons they give for why you should do it. The idea is to help children to see that every opinion is not equal – that the reasons given for a belief or action can be evaluated, and some reasons are better than others. Just because someone, even an adult, says something is true, this doesn’t make it true.

Should we be encouraging children to seek the reasons for what they are told or are asked to do? Some parents and teachers might wonder if this is wise. Young children in particular already ask lots of ‘why?’ questions, sometimes making the adults in their lives weary. Do we want children to ask even more questions?

I think the answer is yes. The more accomplished children become at framing good questions, the more able they will be to think clearly and competently for themselves. And although it is true that at early ages children do ask many questions, their questions often are not taken seriously. Although people frequently remark that it’s important to them that children learn to ‘think for themselves’, in general children are told what to think far more often than they are encouraged to think independently. However, it is crucial that children do learn to think independently. If children are to develop the skills to make good decisions on their own, they must be comfortable questioning what they are told to do by their peers. Likewise, the ability to evaluate information in an analytical way is crucial to discerning what matters and what does not, what is reliable and what is not – especially for today’s children, to whom more and more information is presented more and more rapidly. Young people need to develop confidence and facility at asking critical questions about what is presented to them.

It should matter to us that children learn to think for themselves. And in order to become adept at doing so, children need practice. Tinker Thinkers is a great place to start. Colorful, fun and engaging, the book can help foster some basic reasoning and logic skills, supporting childrens’ development into more self-reflective and proficient thinkers.

© Dr Jana Mohr Lone 2015

Jana Mohr Lone is the Director of the University of Washington Center for Philosophy for Children, and the author of The Philosophical Child (2012).

• Tinker Thinkers by Susan Gardner and Amy Leask, illust. Ami Moor, Enable Training & Consulting Inc, 2014, 40 pages, $11.99/£5.89, ISBN: 1927425085