Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

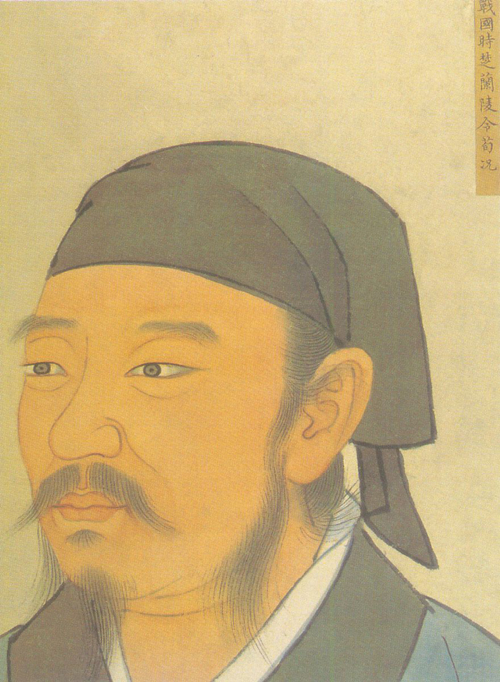

Xunzi (c.320-235 BCE)

Dale DeBakcsy thinks diligently about Xunzi’s psychological Confucianism.

One of the intellectual crutches you’re first given as a Western student of Chinese philosophy is the idea of Confucius as Socrates, Mencius as Plato, and Xunzi as Aristotle. Thus we remember Confucius (551-479 BCE) as the foundational moralist who speaks only through his students; Mencius (372-289 BCE) as the eloquent inheritor of the founder whose praise contained a subtle push of his master’s words in a new direction; and Xunzi (c.320-235 BCE) as the logician who put everything together. There’s broad truth in that. Like most crutches, this gets you walking – but not incredibly well. For there’s also a good deal in the comparison that blanches one of the most interesting figures in world philosophy – for Xunzi was a fearless thinker who trimmed philosophy of any clutter that didn’t address the question, ‘How do we make a society that works?’

How do we make a society that works?

A Long Life Briefly Related

For all of Xunzi’s importance in the Chinese tradition, we know virtually nothing about him. The two earliest sources we have are those of Sze-ma Ch’ien, written a hundred years after Xunzi’s death, and Liu Hsian, about another fifty years after that. These accounts begin with Xunzi entering the court of the king of Ts’i around 270 BCE, at the age of fifty. The king actively cultivated the development of philosophy by founding a college at Ts’i-hsia and luring eminent philosophers there through the granting of honorary ranks.

Of course, we all know what happens when you get a group of eminent philosophers together. Envy and the mad scramble for status bred the usual slander, and Xunzi, as the most famous philosopher of the time, received the brunt of these sotto voce machinations. The king ultimately dismissed him, and he was left to wander China in search of a wise royal master who would heed his anti-war, pro-Confucian counsel.

Now, speaking against war during the Warring States era of Chinese history might seem like a hard sell; and it was. Xunzi never found his wise, peace-loving ruler, and instead settled for a lowly position as a district magistrate for Prince Ch’uin-shen. He held that position until his eighty-third year, when his prince was assassinated and the new ruler promptly drummed Xunzi out of office, prompting him to retire from public work. At 82, he probably deserved the rest.

This course of career was typical for a philosopher in ancient China. During that era, philosophy went hand in hand with administration – many of the major figures we know today led dual lives as thinkers and as organizers of men, which is another reason why pragmatism rules the day in their writings.

Xunzi’s Revolutionary Conservatism

Xunzi is deeply paradoxical in that, in the name of preserving tradition he made antiquity’s most thorough-going attacks on traditional belief. He stood by Confucius to the letter, but swept a million ancestral spirits out the back door. That is, he couldn’t abide a single alteration in the terms and distinctions that delineated the Confucian limits of each person’s social duty and expectations, but he denied as a matter of basic fact the efficacy of all prayer.

At first glance, this may not make sense: he fights with gusto and spite for the preservation of a name, and shrugs his shoulders at the loss of personal immortality. But if we expand our perspective on his times, his startlingly destructive conservatism starts making sense. He lived during the last years of the Warring States era, when everything that the Chinese thought they knew about society was ground to tatters under the wheels of warfare. During that era of shifting power and armed diplomacy, Confucius’s concern with lavish funeral procedures and linguistic accuracy seemed downright quaint, and a number of philosophers rushed to say so. The founding sage was openly mocked, and sophists not so different from those whom Socrates sparred against (at about the same time in Athens), rose to profit from the abuse of the crumbling Confucian order. By playing wild games with words – confusing their common meanings and referents – these Chinese sophists created cracks in the justice system through which any manner of charlatan might romp with ease, while the common people satisfied themselves with prayers to the ancestors rather than concerted action to actually improve their lot.

Here is Xunzi analyzing the efficacy of spirit propitiation:

“If people pray for rain and get rain, why is that? I answer: There is no reason for it. If people do not pray for rain, it will nevertheless rain. When people save the sun or moon from being eaten, or when they pray for rain in a drought, or when they decide an important affair only after divination – this is not because they think in this way they will get what they seek, but only to gloss over the matter. Hence the prince thinks it is glossing over the matter, but the people think it supernatural. He who thinks it is glossing over the matter is fortunate; he who thinks it is supernatural is unfortunate.”

(The Works of Hsuntze, Bk XVII, Concerning Heaven, trans H.H. Dubs, 1928.)

That’s the honesty of a man who has been an administrator and is willing to at last reveal the cynics behind the curtain. And he’s not nearly done:

“How can exalting Heaven and wishing for its gifts be as good as heaping up wealth and using it advantageously? How can obeying Heaven and praising it be as good as adapting oneself to the appointments of Heaven and using them? How can hoping for the proper time and waiting for it be as good as seizing the opportunity and acting? How can relying on things increasing of themselves be as good as putting forth one’s energy and developing things? How can thinking of things and comparing them be as good as looking after things and not losing them? How can wishing that things may come to pass be as good as taking what one has and bringing things to pass? Therefore if a person neglects what men can do and seeks for what Heaven does, he fails to understand the nature of things” (ibid).

That is about as unambiguous a statement of the impotence of religiosity and the primacy of purely human action that you will see this side of Pietro Pomponazzi (1462-1525), and it could only have come from a culture where the lawmaker and the philosophical theorist were one and the same.

A Shock To The System

Xunzi saw all the chaos and opportunism, the wasted yammering towards an indifferent sky, and at once perceived the root problem: that people were putting too much faith in the unknowable, and not enough in the simple social principles that had bound person to person in China since times of legend. They needed to spend less time meditating and hoping, and more time learning and acting. They needed a profound philosophical shock that would upset intellectual complacency and tell unpleasant truths that could seal the breaches that had been made in the Confucian societal fabric.

He delivered that shock in a series of writings of such stark realism and frankness that they have no equal in antiquity, Western or Eastern. As opposed to Mencius, who had hypothesized that humans are basically good, and improve upon that basic nature through following Confucian principles, Xunzi leveled with us. Human beings are innately evil. They are propelled by desires that bring them into conflicts that are decided to the detriment of the weak. Mencius’s pretty talk about us being basically good might make us feel nice; but it is contradicted by our need for extensive laws and governance. We make and strictly enforce laws to protect us from ourselves – a fact that makes no sense if we’re inherently good, but which follows readily if our nature is basically evil.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that, evil though we are by nature, we are boundlessly perfectible through culture. Xunzi is astoundingly democratic in his notion of human improvement. Anybody can become a great sage, no matter what their origins, as long as they resolve to study, to avoid questions that consume time with no profit (such as anything hinting of metaphysics), and to seek and follow useful criticism. His faith in the improving power of civilization and the self-transformative power of intellectual cultivation is unshakeable. Even living in desperate times, where everything he loved about Chinese culture was being summarily trashed in the name of territory, he held to the idea that correct speech would become correct behavior, would become a beautiful society. But he recast that restored vision of Confucian civilization in a thoroughly secular form, replacing its occasional spiritualism with an instinct for psychological truth. He defended the Confucian funerary practices not in the name of propitiation of ancestral spirits or reward from Heaven, but as a beautiful and useful way of transitioning people through the pangs of grief. Thus sacrificing to the spirits is not about receiving tangible gain, it’s about having a recognized vehicle for cathartically purging anguish. The ceremonial aspect allows those who feel too little to not be conspicuously offensive, and prevents those who feel too much from collapsing. Ceremony provides the middle ground that allows everybody to comfortably and reassuringly go through the waystations of life, and therefore it is valuable in a way that tradition had refused to expound upon. Explanations like these, which explore the human necessity and subtle benefits of precisely those institutions the Warring State sophists savagely mocked, kept Xunzi in the canon even as his view of humanity’s evil but perfectible nature lost ground to Mencius’s more cheerful assessment. He assembled and analyzed the crucial texts of China’s rich intellectual past, and transmitted them in a form that the future could recognize as something as beyond mere Tradition For Tradition’s Sake.

A Chinese Leviathan

Like Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), Xunzi was the sort of conservative whose traditionalism ended up being more radical than the most liberal of his contemporaries. The parallels are striking: both lived in an age of civil war, and took from it similar lessons about the need for civilization to protect oppression-prone minorities – which lessons are remembered almost exclusively, and unfairly, for their negative content. Both men also rejected much of the religious thinking of their day in favor of a psychology-based approach to human institutions and motivations.

But let’s not forget their conservative content: Hobbes ultimately defended the unifying potential of monarchy, and Xunzi was an acidic critic of anything that smacked of unorthodoxy with regards to Confucianism. His sixth book is little more than an extended rap against every philosopher of his age who had the audacity to not interpret Confucius the way that he did. However, unlike Hobbes, who was an avid, if often unfortunate mathematician, Xunzi had no interest in furthering the sciences, or any discernible curiosity in how things work. He considered those questions to be as useless as metaphysical queries. Who cares what heat is, we need to keep filial piety well-defined!

Xunzi’s ideal world is static, where terms stay comfortably what they are because nothing changes, and where people seek wisdom through study of an approved list of books, and enjoy comfort through a reasonable and ordered relation to their society mediated by universally understood ceremony. Nothing evolves in this place, and, for a man who lived through the last years of the Warring States era, that’s perfectly fine. Beneath that inertia, however, there is a pulsing spirit that refuses to be fooled, that cuts through sophistry and theology to insist that if we are to improve our lot it’s down to us and our willingness to act with mutual consideration for each other’s weaknesses. Xunzi had an ecstatic appreciation of our ability to cultivate ourselves through education. He exploded the big deceptions of popular belief in order to illuminate the little truths of day-to-day civility. That intellectual daring warrants something more than the indifferent title of ‘the Eastern Aristotle’.

© Dale DeBakcsy 2016

Dale DeBakcsy writes the ‘History of Humanism’ feature at TheHumanist.com and is the co-writer of the twice-weekly history and philosophy webcomic Frederick the Great: A Most Lamentable Comedy.