Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Interview

Stanley Fish

Stanley Fish is an American literary theorist, legal scholar, and public intellectual. Scott Parker asks him about a particular kind of community.

You’re known for your notion of ‘interpretive communities’. What are they?

The idea of interpretive communities was introduced in order to bypass and outflank a traditional question in literary interpretation. That question was, where does meaning reside? Does it reside in the text, or does it reside in the reader? People had been debating those two answers for a long time. I pointed out that neither the text nor the reader had an independent status that would make the question intelligible. Each would have to be a separate freestanding unit competing with the other for the claim of producing meaning. But if you regard both readers and texts as situated together within what I began to call ‘interpretive communities’, then the question disappears, because the subject-object distinction that is normally assumed is no longer in operation.

Photo © Jay Rosenblatt 2016

Who makes up an interpretive community?

This is often misunderstood. An interpretive community is not a community of people who share a point of view or a set of interests, for example, the community of Star Wars fans. An interpretive community is a community made up of people who by virtue of their education and initiation in practice now have consciousnesses which are in a sense community specific. They walk around the workplace or their arena of practice, and merely by looking out, see that arena or workplace already organized in specific ways that are meaningful, in ways that can be read. To bring this rather abstract idea to a particular example: when my students and I walk into a classroom a couple of times a week, neither my students nor I have to look around the room and, pointing to the blackboard, say, “Well, what’s that for?” or, “Why are the seats arranged this way?” or, “How long are we supposed to be in here and what are we doing?” All of these questions and a million others have already been answered by virtue of our membership in the interpretive community that might roughly be called ‘higher education practice in America’. The people who are members of that community don’t think about it, and consequently, the knowledge they have is the result of being a member of the interpretive community. It’s not reflective knowledge – it’s not knowledge that they have to dredge up or examine every morning – it’s knowledge that comes with them because they are themselves now, in a sense, interpretive community property.

When you’re accused of being a dangerous relativist and so on, do you think it has something to do with a misunderstanding of ‘interpretive community’?

It might. Although I can see why the claim of relativism might be relevant. One of the things that goes along with the idea of interpretive communities is the idea that standards of judgment are in a sense community-specific rather than general or universal. This means that how things are debated and assessed and given meaning in a community won’t be translatable into other communities, and certainly not into some general epistemology. So in that way I suppose the charge of relativism is possible. However, if like some people you think of relativism as the loss of the right to call anything right or wrong, accurate or inaccurate – this does not follow from the idea of the interpretive community, because within the normative practices that guide the consciousnesses of community members, judgments of right or wrong, of appropriate or inappropriate, and all the rest of them, are completely available, and in fact are in most cases obligatory. It’s just that you can’t generalize from that or from the norms informing those practices to some general impartial norm that holds for all interpretive communities or can arbitrate between them. That doesn’t mean that any member of an interpretive community is a relativist. He or she only becomes a relativist when philosophical questions are asked. And part of my general thesis about philosophy is that posing philosophical questions has very little to do with anything in our lives except when we happen to be in a philosophy seminar.

As an example, what kinds of arguments would you give against creationists or global-warming deniers – those who many would say are objectively wrong?

Let’s take creationists. One of the differences between science as an activity and other activities – let’s say literary criticism or historical interpretation – is that the rules and protocols are quite fixed and settled in the scientific world, at least for a time. So it’s much easier in the scientific world to say to someone who wants to come into it, “The kind of thing you want to do is not done around here,” or, “That’s not science.” And that’s precisely what is said to the creationists. In fact, it was said in a court in Delaware not too many years ago, when Judge Jones flatly declared, “Creationism is not a science.” Now the question is, did his judgment come from some objective set of standards, or did it come rather from the structure of authority that happens to exist in a certain practice? This structural authority is itself able to change – although in the world of science, change is much slower and much harder to accomplish than it would be in the world of literary criticism, for example. One of the people who testified in the court proceedings that led to the Delaware decision was a sociologist who pointed out, somewhat in the spirit of Thomas Kuhn, that what we’re dealing with here is a disciplinary structure where those who are judging whether or not creationism is a science think of themselves as the guardians of scientific assumptions. So I would say that because of the strength of the authoritative structures that are important in science, the likelihood of intelligent design getting a serious hearing is right now very small. And it may remain very small. But I would also say that it’s not impossible that one day there will be a new account of what is scientifically probable or improbable, that would open the door to intelligent design being considered scientific.

Issues like this explicitly cross over into politics all the time, but politicians are not scientists. What are we to do about Kansas [where creationism is taught in schools as an alternative theory to evolution]?

Politicians are not scientists. Neither are judges. Judge Jones based his pronouncement on statements he read from the American Association of Science. In every area of life, the kind of evidence that might be brought forward is always, shall we say, rhetorically produced. So in Kansas the degree to which scientific evidence will be put forward, and which scientific evidence will be put forward, will depend a lot on the prevailing culture. I can imagine some situations in which the offering of statements by scientists as evidence will be dismissed either because of some general suspicion of scientists or a specific suspicion that scientists are almost always anti-theological. The mix here is always a rhetorical and political mix. There’s no objective yardstick for judgement that can be found in any of these landscapes, although there are yardsticks that are so well established by convention that they stand in for what we think of as the objective, and they work quite well. What you’ll never find is the ‘real thing’ – that objective or Archimedean point of reference in relation to which competing claims can be confidently dismissed.

You wear a lot of intellectual hats –

Let’s say I pretend to. Whether I successfully wear them is another question.

One of them is that of the public intellectual. What is your role in that capacity?

I think my role in that capacity is to take arguments or ways of talking that have become entrenched, take them apart, and say, “Well, no, I don’t think that works” or, “Perhaps we’ve said this kind of thing for too long without thinking about it, so let’s think again.” It’s not to push people in some direction or another, which is what most opinion columns do. So often after reading a column, my readers complain that they never could quite figure out where I stood on the substantive issues that might be raised by it. And that’s right. For the most part I wasn’t standing anywhere, substantively, I was just trying examine arguments and see how they work. I have a book that’s just come out, Winning Arguments (Harper Collins), in which I continue this project, not of trying to persuade people to vote for this candidate or support this policy, but just trying to get people to understand the way in which the world of argument, which is the world we necessarily live in, works.

So the reader understands how arguments work. What are they supposed to do with that?

I don’t know. I guess people who are alert to the argumentative practices in which they are inevitably involved could become a little better at them. But I’m not sure of that. One of the big chapters in Winning Arguments is on domestic or marital arguments, but I think – in fact, I know from my own experience – that a deep or nuanced understanding of the way that domestic arguments work between spouses is not going to help anyone who tomorrow morning finds himself or herself in the middle of a domestic argument.

Is that the distinctive Fishian move?

It’s a two-step. Step one: The coherence of this particular practice or concept is illusory. Step two: Yeah, so what? Nevertheless, even in the absence of being tethered to some foundational ground, if this questioning activity does some good for us in a pragmatic sense, let’s stick with it until something better comes along.

Let’s get back to your argument that philosophy matters only in the seminar room.

I know that for most people who do philosophy or think about philosophy there’s assumed to be a payoff in enhanced understanding that leads to improved behavior. And it’s also often thought that if you have philosophical positions – a series of well-defined answers – on high-theory issues such as ‘What is truth?’ or ‘Where does evidence come from?’ or ‘How can we be certain of this or that?’, those answers will lead to certain kinds of behavior in whatever context or practice you’re operating in. That’s what I’m denying. I’m saying that philosophy itself is a practice with its own traditions and histories, celebrated figures, problems, rewards and penalties, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, but that being good in the game of philosophy doesn’t actually lead you to be good in any other game.

Let’s say I’m a vegetarian and I think I have good reasons for being a vegetarian and I tell you them. If there were some kind of objective truth there, you would be compelled to immediately become a vegetarian.

But there are no such arguments. I just wrote a paper the other day about the old problem of to what extent a liberal society should entertain or give a home to illiberal views, of which fundamentalist religions are usually the examples. There’s a whole industry of brilliant people such as Thomas Nagel and John Rawls devoted to finding a principled reason within the political philosophy of liberalism for being tolerant or welcoming to illiberals. But there just isn’t one! There’s no reason, independent of someone’s preferences, for either tolerating or not tolerating them. Whenever arguments are going to be persuasive, they will always be persuasive because they are rhetorical or political. There are no other kinds of persuasive arguments.

Yet if I became a vegetarian because of reasons I heard, then ideas do have consequences.

I never said ideas don’t have consequences. I said that philosophy doesn’t have consequences. Let’s take the idea that women should be treated equally in the workplace. If I believe, for whatever reasons, in the concept of equal pay for equal work, and I own a business or am part of the governing structure of a corporation, then I’m going to act on those convictions, insofar as I can. That’s because of an idea. But if I believe that statements of fact are either backed up or tethered by some objective standard, or I believe the reverse – no they’re not – then nothing follows in my behavior. That’s the difference between an idea, which will have consequences for behavior if you are strongly committed to it, and a philosophical position, the only consequence of which will be that when you hear some opposite philosophical position you will think it wrong. That’s the only consequence. And when you change your mind in philosophy, let’s say you migrate from a realist view to a pragmatist view, or whatever, what will have changed are the answers that you will give to a set of questions in philosophy. Nothing else will have changed.

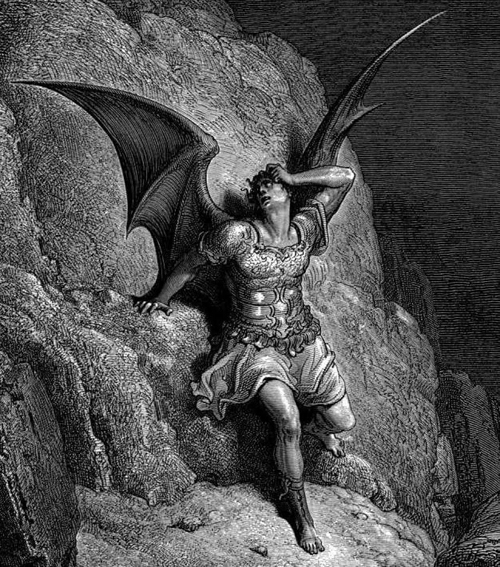

Is Satan the hero of Paradise Lost? Lucifer by Gustave Doré

What motivates you to do this kind of work?

I don’t know. In my academic work I’m interested in argument and in giving answers to questions that have been around for awhile, in whatever discipline I’ve entered. To give an example, the oldest question in Milton studies is, ‘Is Satan the hero of Paradise Lost?’ So I took that up. It’s as if once you enter the Milton community that’s the question you have to take a stand on. I find that in any context I’ve entered I gravitate toward those questions that are longstanding and are thought to be the basic questions facing the practitioners of the discipline, and I take my turn at trying to figure out the best account of the matter. I like following arguments through, making distinctions, and so forth. And I find in that an aesthetic pleasure.

Scott F. Parker is the author of Running After Prefontaine: A Memoir (2011) and Coffee – Philosophy for Everyone: Grounds for Debate (2011), coedited with Mike Austin.