Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Voltaire (1694-1778)

Jared Spears looks at the cometary career of a celebrity revolutionary.

Imprisoned inside the walls of the Bastille in 1717 accused of composing poems which mocked the family of France’s ruling Regent, twenty-three-year-old writer François Marie Arouet was hard at work on his first play. He later boasted that his cell offered him quiet time to think. It seems Arouet took this time to ruminate over the injustice of the charges: the subject of the play bears the unmistakable irony of satire. He chose to adapt Oedipus, the classic Greek incest tragedy. The irony? The Regent, whose family Arouet had allegedly defamed, was widely rumoured to have carried on relations with his own daughter. Drawing such an unabashed comparison, the play was destined to spark controversy, even before opening. But while libel was a punishable crime, satiric insinuation was not. As if to make sure of his inculpability, the author for the first time graced his work with a nom de plume, a single word: Voltaire.

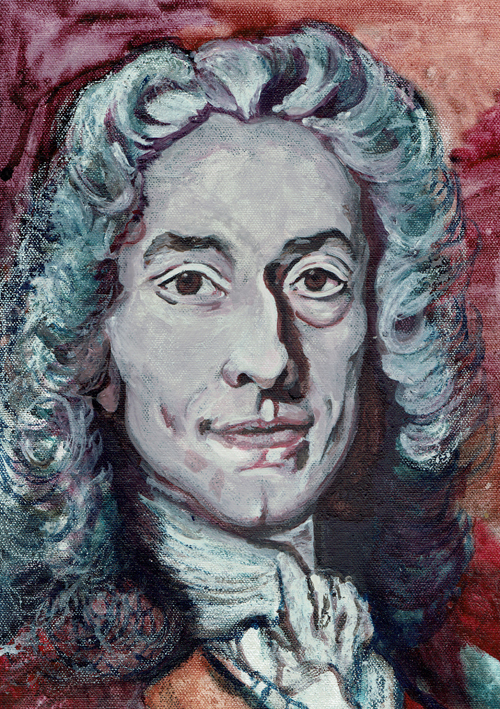

Voltaire by Gail Campbell, 2016

This vignette of the rebellious young writer coining his now notorious pen name is in many ways characteristic of Voltaire’s entire life. Throughout a long career, Voltaire was never a stranger to controversy. On the contrary, he courted it, revelling in every chance to outmaneuver an opponent through rhetorical mastery and biting wit. A natural provocateur ever testing limits, this penchant for feather-ruffling won him admirers as well as enemies. A humanist who championed reason over superstition and tolerance over bigotry, Voltaire helped France cast off a shadow that lingered over it after centuries of religious conflict.

Early Years

Born in 1694 with what’s now diagnosed as Crohn’s disease, Voltaire constantly defied prognoses that he was not long for the world, although the degenerative condition often left him confined to bed. As a boy he received a strict Catholic Jesuit education. From this he acquired two things: impeccable learning, including in Latin, theology, and rhetoric; and an abiding skepticism and mistrust for authority.

Rebelling against his father’s wish to carry on the family practice in law, the young libertine chose for himself the life of a writer. Instead of performing the duties of a notary as his father had arranged, the young Arouet spent his post-college days scribbling poetry and charming the salons of Paris’s social elite. When his deceit was eventually uncovered, his father sent him abroad to serve the French ambassador in Holland, but scandal followed close behind when the impetuous poet fell in love with a French Protestant. The idea of an interfaith marriage was too much for his father to swallow, so the errant son was shuffled back to Paris.

His time abroad in Holland’s more liberal society is often cited as a source of Voltaire’s humanist values, but the sting of a foiled love affair at such a tender age cannot be overlooked. In any case, shaped by the ironies of his early life, his character would be defined by his eagerness to embrace the role of intellectual outsider.

Master of the Art of Shaping Perceptions

Seldom in one place more than a few years, Voltaire’s life was largely that of a wanderer. Never far from controversy, he often left a city in flight, as when faced with the prospect of another term in the Bastille in 1723. The wily troublemaker this time contrived an alternative, commuting his sentence to a period of exile in London. Voltaire’s career had to this point leaned more toward literature than philosophy, but in England’s more laissez-faire market of ideas, Voltaire started to engage with convention-challenging concepts about the universe and man’s place in it.

Warily returning to France in 1726, Voltaire was eager to repair his tattered public image there. Keenly aware of the machinations of noble favouritism, he began a deliberate campaign of literary output and influence-courting in Paris. His tip-toeing around potential controversy in this period paid off, and by the end of 1732 he had taken up residence at court in Versailles – a sign his reputation was restored. While there he struck up a relationship with the Marquise Emilie du Châtelet, whose vivacious personality and remarkable intellect proved an instinctive draw. But his repaired standing and new-found favour at court would be short-lived.

While at Versailles, Voltaire refined and expanded on his Letters Concerning the English Nation, the result of a fruitful infusion of new perspectives while across the Channel. These essays mark his shift toward philosophy and the examination of social mores, extolling such far-ranging topics as religious tolerance of the Quakers to the natural philosophy of English thinkers such as Isaac Newton. Despite Voltaire’s dutifully applying for approval from royal censors, Letterswas illicitly released by its publisher in 1733 without the author’s approval. Causing yet another scandal, the book was banned, even burned, when it appeared in France.

This controversy saw Voltaire’s careful campaign of appearances undone, in part due to his assertions of Newtonian natural philosophy. The concept of a natural world governed by a set of fundamental laws observable and understandable through experimentation had already won over Protestant nations. The French, however, clung stubbornly to their own science, rooted in the work of Descartes, and French Academy elders rejected Newton’s theories. Underlying the discrepancies was a deeper tension between the methods of the two schools. The deductive Cartesian system demanded explanations for why natural phenomena occurred, while the inductive Newtonian method favored empirical investigation, and was content to take nature as it was observed. In Letters, Voltaire broke down Newton’s math-heavy works, and espoused empiricism as a more objective standard of truth over the “useless” Descartes, but his assertion that Descartes “was a dreamer, and [Newton] a sage” was tantamount to heresy among the Academy establishment.

As the debate swirled in Paris, Voltaire and his partner in crime, du Châtelet, fanned the flames by publishing scientific experiments alongside a steady stream of pamphlets and essays in support of Newtonian theories. By the time the authoritative edition of Voltaire’s Elements of Newtonian Philosophy was published in 1745, the tide of French thought had turned away from Cartesianism. Voltaire, standard-bearer of the movement, was credited with dragging national thought into modernity. This was the manifold genius of Voltaire – able not only to synthesize the complex works of Newton and others, but also able to wage a formidable campaign of public discourse.

Theodicy Meets The Odyssey

By 1754, after the untimely passing of his mistress and a tempestuous stint as advisor to Prussia’s King Frederick the Great, the wayward Voltaire found his next cause célèbre. Europe’s many different theological strains had left unanswered questions on the nature of man and the moral implications that followed. Was man inherently good, or inherently evil? Were the course of mankind’s actions divinely preordained? In natural philosophy Voltaire had proved himself a tactful and tireless champion of the ideas of others. Here he would leave his own enduring stamp on Western thought.

This debate was a war of words fought on two fronts. On one side were those such as the young Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who conceived of modern man as corrupted by society, and who praised instead the ignorant simplicity of the noble savage. To Rousseau’s assertions, Voltaire responded that “Reading your works, a man gets the notion to walk on all fours. After more than sixty years I’ve regrettably lost that habit.” He went on to oppose Rousseau’s extremity. “Great crimes are always committed by great fools,” he wrote of him.

On the other side stood Optimists such as Alexander Pope. Heirs of the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, they reasoned that through divine ordination the world which man inhabits must be the best of all possible worlds. No matter how terrible things may seem at times, they asserted that God’s will must be good, and infallible.

For Voltaire, the Optimist’s stance epitomized the dangers of dogmatic faith holding sway over reason. In 1755, an unpredictable catastrophe brought the dubiousness of the Optimist’s thinking to the fore when an earthquake of an estimated magnitude 8.5 rocked the Portuguese capitol, Lisbon. Coupled with the resulting tsunami, the disaster leveled three quarters of one of Europe’s great imperial cities in a matter of minutes. With tens of thousands of lives lost, the horror at this seemingly random calamity left Europe bewildered. Although Voltaire must have been as shocked as anyone at the tragedy, he was outraged by the responses of his adversaries. Rousseau proclaimed Lisbon proof that civilization was inherently a mistake – if the many towers of Lisbon had not crowded so many thousands of people together, how much harm could the earthquake have done? Even more worrying in Voltaire’s eyes was Pope’s Optimistic response, which affirmed the idea that God had surely brought his wrath upon Lisbon to punish its sinful ways.

Voltaire’s initial response, Poem on the Disaster of Lisbon, used high literary form as an entry into the debate. In its verses Voltaire directly attacks the Optimists, writing, “Come, ye philosophers, who cry, ‘All is well,’ And contemplate this ruin of a world.” In humourless sobriety, Voltaire asks how such unpredictable, senseless suffering isn’t a cruel fate. The poem stirred the Paris salons and drew rebuke from Rousseau, but Voltaire’s follow-up would prove the knock-out blow.

The satire Candide was Voltaire’s magnum opus, successfully synthesizing forty years of social criticism and challenges to conventional wisdom into a brilliant example of his literary command. Rich in the author’s trademark ironic wit, the brisk narrative follows its once sheltered young Candide in an Odyssean adventure through contemporary Europe, confronting all the harsh cruelties of this world in a reality check not unlike the fabled experience of the young Buddha. He is accompanied by Dr Pangloss, who after each horror asserts, “Everything must be for the best, in the best of all possible worlds.” The satire struck a stinging blow against religious zealotry, government hypocrisy, and, above all, the philosophy of Optimism. Although thinly veiled in allegory, the book laid bare the shortcomings of that philosophy by reducing it to absurdity.

Published in 1759, Candide was quickly translated into multiple languages, rapidly becoming a best-seller despite being banned in France. The book’s familiar format – it satirizes the narrative clichés of the popular picaresque novel – made it accessible to any literate person of the time, rendering Candide capable of spreading Voltaire’s rebuke out from the salons and into the wider public consciousness. One contemporary that year speculated that it had been the fastest selling book ever.

The far-reaching results of this work cannot be overstated. The minds behind the democratic revolutions in France and America in the following decades were in no small part influenced by the notion of individual free will set forth in Candide.

Final Acts

Voltaire finally settled down in 1759 in Ferney in France, near the Swiss border. Installed here for the next two decades, he received visitors from across Europe, corresponded with leading thinkers the world over, and published numerous new works. ‘The Great Voltaire’, as he came to be known, never ceased his work, and continued to engage in events which captured public attention, such as the 1763 affair of Jean Calas.

Voltaire elevated this case of religious persecution against a wrongly-accused provincial Protestant to national scrutiny. Calas had been tortured and executed for the murder of his son, despite evidence of his son’s perjury and suicide. Once more, outrage stirred Voltaire into a vigorous campaign of letters, opinion columns, pamphlets, and petitions. This time, the intervention of the ‘Patriarch of Ferney’ prompted an almost immediate response. King Louis XV received the Calas family and annulled the sentence. A new trial found Calas innocent and posthumously exonerated the wrongly accused citizen.

The incident is a testament to Voltaire’s now unrivaled influence and stature. It also exemplifies one of his most enduring lessons: exercise restraint over impulsive judgement and action when our emotions might otherwise get the better of us.

In February 1778, Voltaire made his first trip to Paris in twenty years. He came for the opening of his latest play, Irene, and was greeted at the theater with a hero’s welcome. The members of the French Academy who had so bitterly pitted themselves against Newtonian theory some four decades earlier now exalted the man who had survived to witness the birth of his own legend. But at the age of eighty-three, this last trip proved too much for Voltaire’s constantly bedeviled health. For one who referred to himself as “dying since birth” he had managed to cheat death long beyond the wildest expectations, but he died soon after returning to Paris.

A long-standing opponent of the Catholic church, Voltaire was denied a churchyard burial. But his remains would not rest long in the ground. Just fourteen years later, they were resurfaced on the order of the French Revolution’s new National Assembly, to be interred in the Panthéon, where the Assembly decreed the most admirable sons of France were to be laid to rest.

An Enduring Legacy

Voltaire was so incessant in his attacks, so adapt in wielding both wit and reason, we who look back from today cannot help but admire him, and today he is exalted as a preeminent thinker from the era history has called the Age of Enlightenment.

It is perhaps easy to think of the Enlightenment and its achievements as just another inevitable step in the long march toward Modernity. But freedoms which form the basis of Western society today – the freedom to think, speak, and act as we choose – were then only the fancy of a few scribbling idealists such as Voltaire. It took courage to provoke the powerful and challenge commonly-accepted ideas to advance more humane ones. Conceiving mankind as neither irrevocably predestined for glory nor utterly doomed, Voltaire showed that despite its perennial imperfections, humanity could nevertheless strive toward virtue. His life, advocating reason although he was at times vain, and tolerance although he was at times vehement, is itself proof of the wide-eyed realism he espoused.

So what can we make of the legacy of Voltaire? His ideals have been used to mould our modern democratic societies, and for that we can rejoice. But we must remain sober in acknowledging the ways in which history is bound to repeat itself. “What makes, and will always make, this world a vale of sorrow,” Voltaire warned, “is the insatiable greediness and the indomitable pride of men.” So it falls to each era to confront these ever-shifting shadows as they appear to every generation and place. We can be grateful then to inherit the privilege, and responsibility, of Voltaire’s legacy – to stand that much bolder on the shoulders of a great man, who employed wit and wisdom in an unfinished quest for greater justice and humanity.

© Jared Spears 2016

Jared Spears is a writer and researcher in New York. His work can be found at LitHub, Mental Floss, and elsewhere on the web.