Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Obituary

Derek Parfit (1942-2017)

Jeff McMahan says farewell to a friend.

Derek Parfit, who died unexpectedly on the second day of the new year, was one of the most important philosophers of the past half century and, in the view of many, the single best moral philosopher in more than a century. His imaginative but also meticulous and rigorous arguments have transformed the ways in which philosophers, economists, political and legal theorists and others think about many moral issues. He was also an endearingly eccentric and even saintly person.

Parfit was born in 1942 in China, where his parents were medical missionaries. When he was still young, they returned to the UK to live in Oxford. He won major scholarships, first to Eton College, where he was nearly always at the top of the regular rankings in every subject except maths, and then to Balliol College, Oxford. His undergraduate degree was in modern history and was the only academic degree he ever received.

When he left Eton as a teenager, he traveled to New York to work for The New Yorker, in which he published a poem. When he arrived in the US and presented his passport, the immigration official insisted that he required a visa, as he was Chinese. When Parfit protested that he was British, the official went to consult a superior and on returning announced, in words prefiguring the Trump era: “You’re in luck: you’re the kind of Chinese we like.”

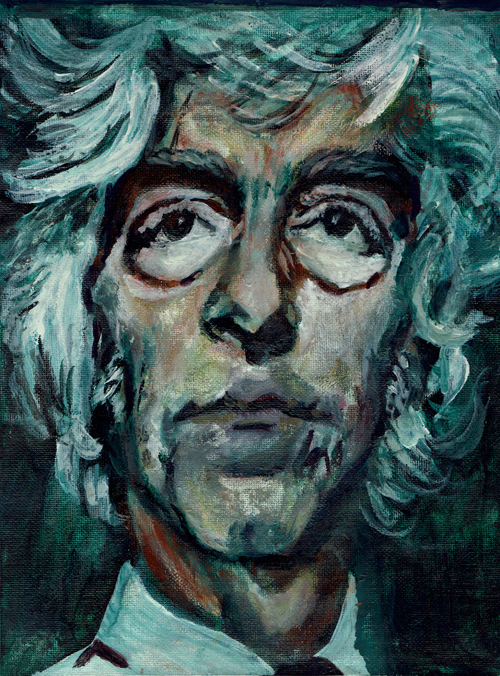

Derek Parfit by Gail Campbell, 2017

After completing his undergraduate degree, Parfit returned to the US on a Harkness fellowship that enabled him to audit graduate classes at a couple of Ivy League universities. Reports of the brilliant comments by the young Englishman with no training in philosophy immediately began to spread throughout the philosophical establishment and have become part of his legend.

On his return to the UK he was elected to a fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, where he remained until he became 67, when he was required by the university’s mandatory retirement policy to leave both the college and the faculty of philosophy. He was able, however, to retain his appointments as regular Visiting Professor at Harvard, NYU, and Rutgers until his death, much to the benefit of those departments and their students. It was only after he had become too old to be allowed to teach at Oxford that he published the great magnum opus of his later years, the three massive volumes of On What Matters, the third of which appeared only a couple of weeks after he died.

In 1971 Parfit published his first article, ‘Personal Identity,’ in which he argued both that our continued existence involves nothing more than certain relations among mental states at different times and that what makes it rational for you to care in a special way about some future person is not that that person will be you but that he or she will be psychologically related to you in certain ways. This paper was immediately recognized as a masterpiece and secured Parfit’s reputation in philosophy.

Over the twelve years following the publication of this landmark paper, Parfit worked relentlessly on the manuscripts that were to become Reasons and Persons (1984). This book has often been described as comprising four distinct but closely connected books: one on the ways in which moral theories can be self-defeating, a second on rationality and time, a third that defends his view of personal identity, and a fourth on the ethics of causing people to exist and duties concerning future generations. While each of the four parts has been enormously influential, Part Four effectively created a new, difficult, highly important, and now flourishing area of philosophy known as ‘population ethics’. Peter Singer has described Reasons and Persons as the best work of moral philosophy since Sidgwick’s Methods of Ethics, which was published in 1874.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, material that would, after much rewriting, eventually coalesce into Reasons and Persons began to circulate in photocopies of Parfit’s typescripts. It is perhaps difficult for those who have entered the field of philosophy since that book was published to appreciate how exciting and exhilarating those early formulations of his ideas were. Over the intervening decades, much of moral philosophy has been shaped by the forms of argument, including the imaginative use of hypothetical examples, and even the style of writing that are characteristic of Reasons and Persons. But at the time they were radically different from what philosophers were familiar with. For many of those working in philosophy then, and perhaps especially for graduate students who were able to read some of Parfit’s manuscripts, the novelty, brilliance, and practical significance of his arguments were intoxicating. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that, at least for some of us, that era seemed rather as the French Revolution seemed to the young Wordsworth: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven!”

Parfit had a native genius for philosophy. But he also devoted more time and concentrated effort to the development of his ideas than any other philosopher I have known. He once mentioned a passage in a book of economic history that noted that the concept of work had sometimes been understood in such a way that work was necessarily unpleasant. On this understanding, Parfit almost never worked. Yet throughout his adult life he did little other than think about, read, and write philosophy. When I visited Oxford in January and February of 2014, I stayed in his house. During those months, he left the house only a few times. In all but one instance, he left only to walk a few blocks to buy fruits and vegetables for his spartan meals. The other instance was when he walked with me to an appointment I had so that we could continue the philosophical discussion we were having. The one exception to his monomaniacal commitment to his philosophy was his architectural photography, samples of which appear on the covers of his four books. But he gave that up many years ago when he came to fear that he might not live long enough to complete his remaining work in philosophy.

There are many anecdotes about the ways in which Parfit simplified his life to take as little time as possible away from his work. He ate only twice a day, with almost no variation in what he had at each meal. He ate cold food only, mostly fruits and vegetables without any preparation. Even when he could have had freshly ground coffee with only a minute’s additional preparation, he drank instant coffee, often with water straight from the tap. He sometimes kept a book open on the chest-of-drawers so that he could read while putting on his socks. His speed in reading was phenomenal, in part because his power of concentration was prodigious. Wanting to preserve his mental and physical capacities, he took an hour every evening during his last decade to get vigorous exercise on a stationary bicycle, but never without reading philosophy (or occasionally physics) while furiously pedalling.

Parfit’s kindness and generosity, not only to his students and friends but to others as well, are legendary. The comments he gave to people on their manuscripts were sometimes longer than the manuscripts themselves, and the comments were invariably articulated in the gentlest, most tactful, encouraging, and constructive way possible. He frequently wept, not for himself but always from compassion for others.

A couple of years ago, when he was teaching at Rutgers, he experienced a confluence of medical problems that urgently required that he be anesthetized and placed on a ventilator. When he was allowed to emerge from the sedation nearly 24 hours later, he groggily gestured for pen and paper. His first scribbled thoughts were concerns about his teaching commitments and a thesis defence in which he was supposed to participate at Harvard. When the ventilator tube was removed and he could again speak, he immediately began to discuss with me the ideas and arguments on which he had been working when I had to rush him to the emergency room. That he was in the intensive care unit seemed not to interest him, and he was largely incurious about what had happened and about what his diagnosis and prognosis were. Even in those circumstances, it was his ideas that mattered most.

The next day, Johann Frick, the graduate student whose thesis Parfit was scheduled to examine, came for a visit, during which Parfit delightedly insisted on discussing the thesis with him for several hours. A nurse, having noticed how many visitors Parfit had had, exclaimed, “Jesus Christ had only 12 disciples – but look at you! You’re clearly a very important man. What do you do?” “I work,” Parfit replied with a smile, “on what matters.”

© Jeff McMahan 2017

Jeff McMahan is White’s Professor of Moral Philosophy at Oxford University, a distinguished research fellow at the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and a fellow of Corpus Christi College.