Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Street Philosopher

Acceptable In Amsterdam

Seán Moran tiptoes tolerantly through the tulips.

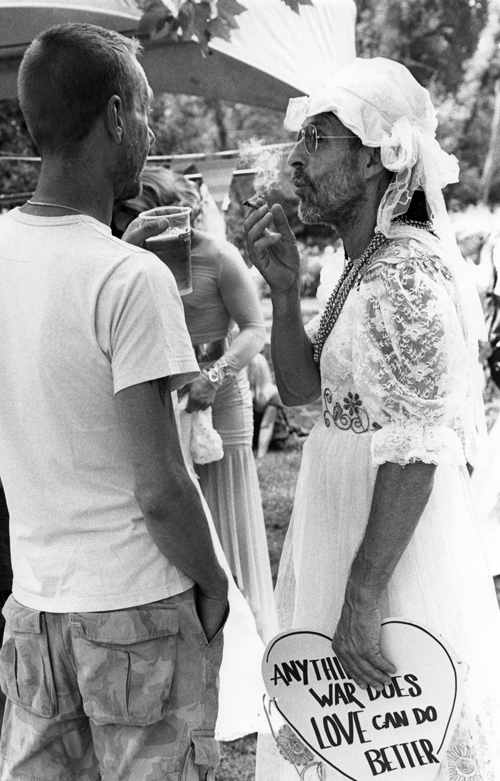

The bearded man wearing a white wedding dress in my photograph seems to be smoking a joint. Since this was Amsterdam, he attracted no negative attention, as far as I could see. According to a 2015 EU survey, the Netherlands is among the most tolerant countries in Europe with respect to LGBT issues and ethnic background,alongside Sweden, Denmark and Ireland. Though even in the Netherlands things are changing, as I discovered chatting to locals who would know, and observing Dutch politics.

Intolerance seems to be on the rise internationally. The election of Donald Trump in the USA and the Brexit vote in the UK may be partly due to an increasing unwillingness to tolerate difference. ‘We’ have found the right way to live, and will not put up with ‘others’ who are different.

But, you might ask, why shouldn’t we tolerate the man I photographed? As long as passers-by didn’t inhale too deeply, he offered no threat to anyone. And his image, though unconventional, is harmless. Indeed a beard is virtually compulsory (for males) in some quarters: in the pogonophilic – beard-loving – districts of Shoreditch, London, and Brooklyn, NY, for example, where it is an essential part of the hipster-lumberjack look. But beards can also provoke hostility – pogonophobia – in areas where facial hair denotes radicalisation. Other aspects of my subject’s lifestyle could be attacked too: on ethical, medical, religious, political, or aesthetic grounds.

That goes for all of us, though. No matter what you look like or how you behave, there will be someone, somewhere, who would take exception to you and would express their bigoted judgements aggressively. Only recently I was loudly upbraided by another McDonald’s customer for having the temerity to read Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae while drinking coffee. It was just my reading a book in public that provoked his ire, not any specific quarrel with Thomistic metaphysics. If you spotted someone holding Philosophy Now you could be pretty sure that you’d have much in common. This marker of intelligence and sophistication would signal their membership of our tolerant clan. Unless, of course, they were using it as kindling for a public book-burning.

The Progress of ‘Toleration’

The word ‘toleration’ comes from the Latin tolerare, ‘to put up with’. Medieval philosophers defined toleration as permissio negativa mali – a ‘negative permission of evil’ – putting up with wrong-ish things. In later centuries, states began tolerating some theological differences. The Maryland Toleration Act (1649), for example, allowed a measure of religious freedom to citizens (but prescribed the death penalty for anyone denying the Trinity). In A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), the English empiricist philosopher John Locke advocated permitting individuals to hold any private beliefs – apart from Catholics and atheists, that is.

Nowadays, the term ‘toleration’ suggests reluctant permission, while ‘tolerance’ indicates a more kindly, liberal sentiment; but they are practically synonymous. On a personal level, they both inhabit the conceptual region between our approval and our condemnation. This willingness to ‘live and let live’ seems a benign way to go about our day. But while it is an improvement on intolerance, there is something slightly patronising about this attitude of acceptance. The German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe said that “Tolerance should be a temporary attitude only: it must lead to appreciation. To tolerate means to offend” (Maximen und Reflexionen, 1829). In tolerating people, we secretly disapprove of them, even as we outwardly feign acceptance. This dishonesty is vaguely insulting, so we should engage instead in dialogue. After such an encounter, we may no longer look down on them, but start to see things from their perspective, and perhaps show some solidarity. Goethe has a point. Still, nobody likes having their lifestyle examined too closely, even individuals of the same tribe.

In a sense, tolerant people are members of a tribe too – a tribe that others find intolerable. And the feelings are mutual: the tolerant can be vicious when anyone disagrees with them. So the French epithet ‘bien-pensant’ – ‘right-thinking’ – is increasingly used pejoratively against the tolerant tribe, implying hypocrisy, especially concerning matters of the freedom of thought.

Granted, it is sometimes easy to mock open-minded, tolerant practices unthinkingly. At an Oxford conference I was at last year, the chair sensitively asked participants to introduce themselves and state their ‘preferred gender pronoun’, specifying whether we should call them ‘he’, ‘she’, ‘they’, or another term. It was an inclusive gesture to transgender and non-binary delegates, but there were some raised eyebrows. However, we should bear in mind UK research showing that nearly half of “trans people under 26 said they had attempted suicide” (The Guardian, 2014). Having the good manners to use the requested pronoun is a small but important mark of respect which costs the user nothing but avoids adding to the discomfort of those who may be suffering daily from hostile misgendering, exclusion, and abuse by intolerant strangers.

Keeping up with the terminology is a challenge for the penseur who aspires to be bon, though. The abbreviations of identity politics are becoming increasingly all-encompassing. The longest I’ve seen in print is LGBTQIAGNC, which stands for ‘Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, Gender-Non-Conforming’. Even this leaves out some variants, such as ‘Pansexual’ and ‘Questioning’. Some people advocate streamlining all of these into the acronym GLOW (Gay, Lesbian, Or Whatever), but this is rather dismissive of the ‘Whatever’ folks. How about the Irishism ‘Quare’, instead?

Group Toleration

‘Othering’ the stranger and those who are different has a long history, because xenophobic sentiments do have a sort of logic behind them (although they have outlived their usefulness). Back in Paleolithic times, someone from outside one’s own hunter-gatherer tribe, or just out of step with its norms, represented a threat. Through the lens of survival value, therefore, it served us well to view the unfamiliar and the unusual with suspicion. The Ancient Greeks called people from other places ‘barbarians’ because to their ears, foreign languages sounded like “bar bar bar.” Regarding them as ‘other’ – as not fully human – removed any residual guilt at mistreating or enslaving them. The Third Century BCE Roman writer Titus Plautus expressed this de-humanising of the stranger tellingly: homo homini lupus est ; “man is a wolf to man” – that is, to those who don’t know him.

The tribal shibboleths that differentiate friend from potential foe can be very subtle. Sigmund Freud wrote of the “narcissism of minor differences.” We think so highly of our own tribe that even slight deviations from our norms become unduly important. In the Monty Python film Life of Brian (1979), we see the mutual hatred between the Judean People’s Front, the People’s Front of Judea, and the Judean Popular People’s Front.

It’s easy to be smug. When Tony Blair was UK Prime Minister, he said in a 2006 speech to Muslims, “Our tolerance is part of what makes Britain, Britain. Conform to it; or don’t come here.” His word ‘conform’ betrays the intolerant motivation of some apparently benign pleas for tolerance. Such talk demonises certain ‘other’ groups as being intolerant, as opposed to “our tolerance.” And there is something self-refuting about showing intolerance towards the allegedly intolerant. Like (real) lumberjacks inadvisedly sawing off the branch upon which they sit, those intolerant of intolerance will fall from their lofty perch, having forgotten their own principle.

Tempering Toleration

But of course some things are intolerable. Cruelty, for example. So what is a reasonable stance to take towards a world that presents us with multiple annoyances, of various levels of seriousness? Perhaps the Aristotelian notion of ‘good temper’ is one solution. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle placed this virtue at a mean between the twin vices of irascibility and inirascibility (roughly, apathy). Much like the UK comedy character Victor Meldrew (catch phrase: “I don’t believe it!”), the irascible person is easily provoked to angry disapproval. At the other extreme, apathetic people are totally indifferent to whatever they observe. No evil can rouse them to righteous anger. The middle way, good temper, is the virtuous disposition.

Since we’re discussing intolerable evil, it’s inevitable that Godwin’s Law will apply and the Nazis will appear (Mike Godwin claims that the probability of this approaches one the longer a discussion continues). I use vintage Leitz cameras to take the photographs for this column; the oldest was made in Germany in 1932, just before Hitler came to power. But while the Third Reich was notoriously intolerant, the Ernst Leitz factory technicians had an interesting approach to (engineering) tolerance. (The technicians also helped many Jews to survive, earning Leitz the title ‘the photographic Schindler’.) In modern production, components whose measurements fall outside specified limits will typically be rejected. Not so in the heyday of precision hand assembly. Neighbouring components were modified slightly to accommodate the out-of-specification part, so that the finished camera mechanism operated smoothly.

How far ‘out-of-specification’ are each of us? Even if we disallow having a specified essence to live up to, there is still the matter of our socially-constructed self being out of kilter with the society that constructed it. Either way, we are probably less ‘socially perfect’ than we could be. Answering his own question ‘What is tolerance?’, the Eighteenth Century French philosopher Voltaire suggested that since “we are all formed of frailty and error, let us pardon reciprocally each other’s folly.” The deal is that we find a modus vivendi – a way of accommodating the foibles of others, while they in turn overlook our peculiarities. We should all perhaps show an Aristotelian good temper.

In his book Leviathan (1651), the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes proposed that “A fifth Law of Nature is Compleasance; that is to say, That every man strive to accommodate himself to the rest.” If we extend Hobbes’ definition to embrace the full spectrum of men and women – square and quare, smooth, bearded, or shaven – it seems like a tolerably good principle to follow.

© Dr Seán Moran 2017

Seán Moran is in Waterford Institute of Technology, and is a founder of Pandisciplinary.Net, a global network of people, projects, and events.