Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

John Rawls (1921-2002)

Alistair MacFarlane traces the life of an influential political theorist.

John Rawls was the most important moral and political philosopher of his generation. His greatest book A Theory of Justice (1971) is a classic of political philosophy. It introduced a clear and illuminating way in which to consider the concept of justice: Justice is Fairness. Rawls then spent the rest of his life explaining, developing, and expanding this simple, powerful, and inspiring idea.

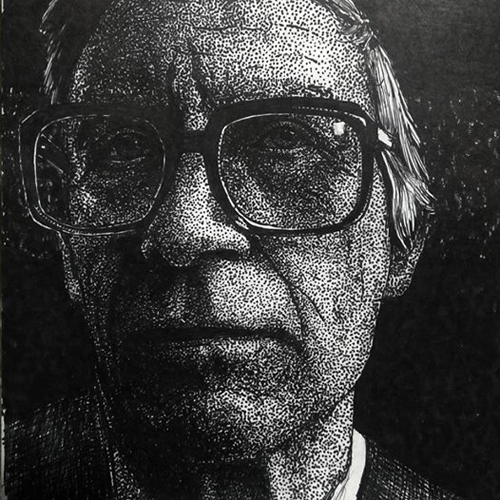

John Rawls portrait by Woodrow Cowher, 2017

Early Life

John Bordley Rawls was born on 21 February 1921 in Baltimore, Maryland. His father William Lee Rawls was one of Baltimore’s leading attorneys, and his mother Anna Abell (née Stump) was active in politics and was a branch president of the League of Women Voters.

Rawls’ young life was marred by a double tragedy. When he was seven he contracted diphtheria, and when a younger brother Bobby visited him in hospital the disease was passed on and Bobby died. Then, two years later, the tragedy was repeated when Rawls developed pneumonia and passed it on to his other young brother, who also died. The irrational conviction that he was somehow responsible for their deaths haunted the youngster for many years.

After primary school in Baltimore, Rawls attended Kent School in Connecticut. Entering Princeton University in 1939 he graduated BA summa cum laude in 1943, then enlisted in the US Army as an infantryman. While at university, Rawls had been intensely religious, writing a deeply religious thesis, and he considered becoming an Episcopalian priest. But the horrors he experienced in prolonged and bloody combat as a foot soldier, where he saw the random capriciousness of death and the effects of war on his comrades, made him abandon his Christian faith. The further horrors of the Holocaust and later the Vietnam War led him to analyse the political systems in which such catastrophic events could occur. He asked himself the fundamental questions: How could democratically elected governments ruthlessly pursue unjust wars? And how could citizens resist their governments’ aggressive policies? Seeking answers to these questions set the course of his future life.

When Japan surrendered at the end of WWII, Rawls was promoted to sergeant and became part of the occupying army. On refusing to unfairly discipline a fellow soldier, he was demoted to private. Severely disenchanted, he left military service in 1946 to pursue a doctorate in moral philosophy at Princeton.

Receiving his doctorate in 1950, Rawls taught in Princeton until 1952, when he was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to go to Christ Church, Oxford University. While there he was deeply influenced by Isaiah Berlin and by the legal theorist H.L.A. Hart. Returning to the United States he became an assistant, then associate, professor in Cornell University. In 1962 he was made a full professor, coupled with a tenure position at MIT. Soon afterwards he moved to Harvard where he taught for almost forty years and trained a generation of political and moral philosophers.

Philosophy

There is a profound difference between the methods and arguments used in science and those used in moral and political philosophy; that is, between considerations of the physical and of the social worlds. The former admits only observable facts, mathematically established knowledge, and rationality. The latter expands its considerations to include mutual agreement, understanding, and reasonableness. The essential difference is that the expanded view needed to handle human interactions must admit plurality. There is no longer any one evident fact of any matter but only a broad consensus of understanding reached following agreement.

The key ideas are clearly expounded in Catherine Elgin’s books Considered Judgement (1996) and Between the Absolute and the Arbitrary (1997). The crucial points are that in any philosophical discussion of social matters:

• There are no establishable facts, only justifiable beliefs; and

• Since absolutely certain knowledge is unattainable, we must settle for a mutually agreed understanding.

Rawls’ thinking accommodates these ideas that in thinking about ethics and politics we must deal with understanding and belief rather than facts and knowledge. In addition to their intrinsic interest, Rawls’ books give a splendid illustration of how coherent arguments about social concepts such as justice can be constructed and deployed under these limitations. In building his methodology for thinking about ethics Rawls uses a Principle of Reflective Equilibrium and a range of thought experiments.

The Principle of Reflective Equilibrium

We seek coherence among a set of beliefs by reflecting upon a broad range of relevant issues. Judgement uses reasonableness (rationality tempered by imagination and scepticism) to balance belief against experience. This process persuades us that some proposed action, or revision of belief, is both reasonable and justified. This approach to inductive thought was first developed by Nelson Goodman in his book Fact, Fiction and Forecast (1955). His idea is that we justify rules of inference by bringing them into ‘reflective equilibrium’ with what we judge to be acceptable inferences by carefully considering a broad range of relevant cases (see Brief Lives, PN 109). The importance of this approach lies in its wide and flexible applicability, covering not only moral and social judgements but also everyday practical decisions and aesthetics, as well as the more formal procedures used in science and technology.

Thought Experiments

Rawls arrived at his principle of Justice as Fairness by using a famous thought experiment. He asks us to forget, so far as possible, all considerations of our own personal circumstances, such as knowing our sex, race, position in society, inherited wealth and good education, or lack of them,and forget even our own previous aims and values. He called this imagining ourselves behind a ‘veil of ignorance’ regarding our present position in society. Being ignorant of our position in society, we must then choose what sort of world we would accept the risk of being born into. In this imagined world, whatever privileges or disadvantages we currently enjoy or suffer under could not be assumed to apply; and Rawls argues that this would force us, after due consideration and reflection, to conclude that we must take into account everyone’s situation equally, so ensuring fairness for all.

The Development of Rawls’ Philosophy

Rawls’ approach to moral and political philosophy was developed over several decades. During this period he defined, elaborated, refined, extended, and re-defined it in four books:

• A Theory of Justice (1971): In this he sets out his concept of justice as fairness, and argues for some principles of justice that he thinks free rational people would accept if they started from an initial position of equality.

• Political Liberalism (1993): Here Rawls extends and revises the idea of justice as fairness. He accepts that the ‘well ordered society’ of his first approach, in which there exists a broad consensus about what constitutes a good life, must be abandoned. In a modern democratic society we must instead accommodate a plurality of incompatible and irreconcilable doctrines. A society cannot be united in a consensus of any such doctrines; but it could be united in a basic political belief of what constitutes justice [see other Rawls article this issue, Ed].

• The Law of Peoples (1999): Rawls now extends the idea of a social contract to an international level, advocating a ‘Society of Peoples’, and lays out general principles that should be accepted by both liberal and non-liberal societies as a standard for regulating their behaviour towards one another.

• Justice as Fairness – A Restatement (2001): Finally, he draws all his ideas together and gives a broad review of his main lines of thought. Rawls maintains that moral clarity can be achieved even when a collective commitment to justice is uncertain.

This is an immensely impressive body of philosophical work. To read it is simultaneously inspiring and daunting. It fills one with a conviction that philosophy has much to contribute to our future development as a species, and that social problems can be approached with the highest level of intellectual rigour.

Last Days

Rawls was incapacitated by a severe stroke in 1995, followed by a series of further strokes. Despite these he continued working, with an increasing degree of physical, secretarial and editorial help. He died at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts, on Sunday 24 November 2002, and was buried on 3 December after a memorial service at the First Parish Unitarian Universalist Church in Lexington.

Rawls was devoted to his family. He was survived by his wife Margaret (née Fox), a Brown University graduate, whom he married in 1949. They had two sons, Robert and Alexander, two daughters, Anne and Elizabeth, and four grandchildren.

Legacy

Rawls had a severe stutter, and this, combined with what one contemporary called “a bat-like horror of the limelight” ensured that he seldom gave interviews or accepted awards. So despite his immense contributions he never became a public intellectual. But his unswerving analysis of social institutions based on a concept of fairness has shown that science has no monopoly in shaping our future. Rawls demonstrated how a broad, more inclusive approach to the human predicament can be developed on a basis of mutual understanding, reasonableness, tolerance, through creating societies of free citizens who hold basic rights, and who, despite widely differing views, could cooperate within an egalitarian economic system.

Rawls combined a profound wisdom with an equally profound humanity. On presenting him with the National Humanities Medal in 1999, President Clinton said that Rawls’ work had helped to revive faith in democracy. We surely need to build on his achievement to secure our future in an increasingly uncertain, intolerant, and complex world.

© Sir Alistair MacFarlane 2017

Sir Alistair MacFarlane is a former Vice-President of the Royal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor.