Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Friendship

Friendly Friar

Seán Moran asks amiable Aquinas about amity.

It’s not Friar Tuck I’m talking about. The jovial gourmand of the Robin Hood stories was apparently a good friend of the Merry Men and Maid Marian in Sherwood Forest. But the religious order of Friars, the Dominicans, was founded in 1216, so it is hard to see how the adventures of Friar Tuck could have taken place in the time of King Richard I as the legend claims, since Richard I died in 1199.

The Friar I’m interested in actually existed. He was a thirteenth century philosopher and Christian theologian who embraced Aristotelian, Jewish, and Muslim philosophers. Like Friar Tuck, he enjoyed his food. In fact his contemporaries called him ‘The Dumb Ox’ because of his large build and hesitant speech.

Friar Thomas Aquinas says some interesting things about friendship. However, his central message on this topic would probably give atheists – and some devout theists – an attack of the conniptions. I’ll come to that in a minute; but for now let me promise that after any conniptions have dissipated, some useful principles still remain.

For Thomas, friendship is the ideal way we should relate to other thinking beings. We ought to be friends with those around us, because this will enrich our lives in virtue (particularly in the virtue of charity, or caritas). Along with Aristotle, Aquinas sees the good life as the virtuous life, and we need friends to receive many of our acts of virtue. There’s nothing too controversial here, we might think.

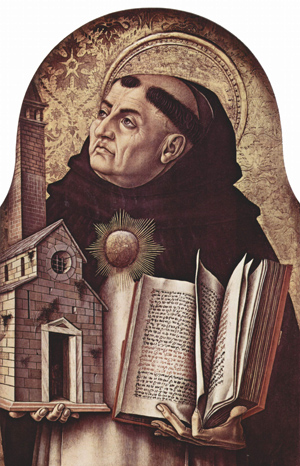

Aquinas looking up to his friend

However, Thomas stretches the notion of friendship far beyond just having warm interactions with the rest of humanity. His analysis centres on friendship with God. (He also wants to befriend angels, so here he pre-empted New Age thinking by several centuries.) Being a chum of the Creator is Thomas’s major insight about friendship; but that idea is problematic for many people. It may strike some as an unreasonable ambition to become an acquaintance of the Almighty, particularly if like Aristotle, Aquinas’s philosophical forebear, you regard only friendships between equals as genuine friendship. So believers who see the gulf between God and humans as immense, will question the Friar’s view that we can befriend God. To them, the difference in our status rules out any possibility of comradeship. Non-believers too will scoff at the idea of divine friendship, perhaps dismissing it as being on a par with wanting to make friends with a unicorn.

I shall not attempt to defend Aquinas’s position against these two objections, but I will suggest that some of the inferences he reaches still apply today, whatever our religious orientation or absence thereof. This is a reasonable thing to do. Even though unicorns and mermaids do not exist, it is still true that a mermaid riding a unicorn would be well-advised to do it side-saddle. And we can draw sound ethical implications from counterfactuals too. For example, were we to come across a mermaid in a tizzy because her unicorn was choking after eating a leprechaun’s stash of gold coins at the end of the rainbow, we would have a moral duty to help as best we could, and not just for the stunning selfie. The point is that we don’t need to be comfortable with all aspects of an analysis to accept its conclusions.

Thinking Ahead

In his analysis of friendship, Aquinas is looking ahead to the afterlife. There, he hopes, we can live in the beatific vision of paradise, in which we enjoy the bliss of being in God’s company, together with the community of the blessed who have made it there too. So, he reasons, we should be friendly with fellow human beings now, because in the future they may, with us, be friends of God. The principle is pretty much “any friend of God’s is a friend of mine”.

A further reason is that being friendly to everyone is simply the charitable thing to do – not in the sense of ‘charity’ as cash donations to those less fortunate (although it could include that), but taken to mean a generally benign disposition towards those we encounter.

This is a guideline many people can probably accept. It’s a subset of the Golden Rule that most religious and secular codes contain: ‘Treat others as you would like to be treated’. Charity also has something in common with Immanuel Kant’s Categorical Imperative, which he believes is binding on all of us. This Imperative says that we should “act only in accordance with that maxim which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law” (Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals, 1785). So if we would prefer to be treated in a benign way (rather than a malign one), for the sake of consistency we ought also to behave in that same way towards others.

Kant’s criterion of universalisability falls down in some cases, though. For example, lawyers might want to be treated benignly, and perhaps even occasionally manage a bit of beneficence of their own, but they could not consistently will that everyone act so, since their income would soon run dry if what Shakespeare termed ‘the milk of human kindness’ were to flow too freely. (Aristotle recognised this too in his Nicomachean Ethics: “When men are friends they have no need of justice.”) However, for non-lawyers, it is rational to wish beneficence, friendliness, and charity to be universal.

Aquinas agrees, but he defines ‘charity’ in a way that sounds strange to modern ears: as “the friendship of man for God” (Summa Theologiae). A charitable attitude towards our fellows is merely a secondary manifestation of this virtue. God is its primary focus. To be friends with God the supernatural virtue of charity is needed, and this rubs off in our dealings with mere mortals.

The Key Effects of Friendship

Not everyone shares Thomas’s analysis, of course. So, as a conniptions-avoidance strategy, let us put to one side Thomas’s metaphysical baggage, and see what aspects of his account of friendship are philosophically interesting irrespective of our beliefs.

Thomas says the three key effects of friendship (whether human, angelic or divine) are concordia, benevolentia, and beneficentia. Concordia brings us into some degree of alignment with our friend, by our willing the same general ends as they do. The specifics may differ, though. As Aquinas explains, concord between friends is “a union of wills, not of opinions.” His distinction between benevolence – good will – and beneficence – good action – is also a useful one: we may want good things for our friends, but if the friendship is genuine, those good intentions will be followed through. On this analysis, British writer Somerset Maugham’s assertion that “It’s not enough that I succeed, my friends must fail!” can’t be referring to real friends. If they were genuine, his sentiments towards them would be benevolent, and his actions beneficent. What he describes is a type of Schadenfreude – deriving pleasure from the misfortunes of others. If he enjoyed outstanding financial success for his writing (which he did) while those close to him failed in their projects, this would increase the distance in accomplishment and status between him and his benchmark ‘friends’.

Thomas Aquinas would have decried Maugham’s way of looking at human relationships. Spoiling friendships of all types, according to him, is the vice of pride. This analysis is also not entirely convincing today, because in the twenty-first century the term ‘pride’ has taken on a generally more positive meaning: ‘Gay Pride’, for example. Pride was also seen as a virtue by Aristotle, who valorised the megalopsychos, the ‘great-souled man’ who had intense pride in his elevated social status and lack of dependence on anyone. And centuries before him, Homer depicted noble characters such as Odysseus who valued their proud heroic reputations (kudos) above everything. But Thomas understands the concept in a different way. He sees pride as an arrogant and unwarranted overestimation of our own excellence. Such a feeling of superiority to others is a barrier to friendship, both human and divine.

Thomas promotes humble friendships with fellow human beings as part of his overall belief system in a benign God who can also be our friend. To him, people have a value completely unconnected to their social status, financial success, beauty, intelligence, celebrity, usefulness to our careers, and so on. To Aquinas, they have value just because they are made in the image of God and also have the potential to be a friend of their Creator.

That’s one way of looking at friendship. It is only convincing to theists, though; and perhaps just the subset of those who don’t find the notion of friendship with God too hubristic. (In one trope of Greek mythology, hubris – the pride of putting oneself on a par with the gods – is punished by nemesis. Icarus’s hubris in flying too close to the sun, for example, resulted in the nemesis of his wax-and-feather artificial wings melting).

Even without Thomas’s metaphysics, we can still accept the principle that we ought to be friendly to other human beings in a non-proud way. Unlike the arrogantly self-sufficient megalopsychos of Aristotle, we are nowadays interdependent in several respects. One of these dependencies relates to knowledge. So, if we only ever befriend people like ourselves, our knowledge-base will suffer from being too narrow. In surveying knowledge, as in surveying terrain, a wide baseline for triangulation is desirable. To widen it requires us to entertain (though not necessarily accept) the opinions of others across an expansive social, cultural, political, gender, and ethnic landscape; and our epistemic mission should be animated by a spirit of concord – ‘a union of wills’, as Aquinas puts it. This can act as an antidote to the echo-chamber effect of only having friends (real or virtual) who share our opinions. As a bonus, we can also experience the pleasure of enjoying a wide range of culinary delights in the company of our varied friends. And that is something of which both Friars, Tuck and Thomas would heartily approve.

© Seán Moran 2018

Seán Moran is a philosopher at Waterford Institute of Technology, Ireland, and is a founder of Pandisciplinary.Net, a global network of people, projects, and events.