Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Philosophy For Non-Philosophers by Louis Althusser

Neil Richardson philosophises on what Louis Althusser has to say to non-philosophers.

“The scholar who cherishes the love of comfort is not fit to be deemed a scholar.” – Confucius

I requested a paperback through my local library, my curiosity triggered by its title, Philosophy for Non-Philosophers (2017), which suggested that an innovative author had somehow compressed renowned works into a text for newcomers. I expected sections within the book to discuss logic, language, ethics, and mind, before weaving the strongest threads of such topics into a robust conclusion – philosophy for today’s remarkably diverse public. Louis Althusser’s book in fact holds twenty-two frequently dense chapters: perhaps too many for the paperback’s two hundred pages and a prospective audience which includes ‘farmers and managers’. By way of illustration of the nature of the contents, his opening chapters are titled, ‘What Non-Philosophers Say’, ‘Philosophy and Religion’, and ‘Abstraction’; the last three are ‘Philosophy and the Science of Class Struggle’, ‘A New Practice of Philosophy’, and ‘The Dialectic: Laws or Theses?’

For Louis Althusser (1918-1990) – who turns out to be a French Marxist philosopher – idealist philosophers live in closed world, endlessly rereading their great teachers Plato, Hegel, and Descartes, whose works are overloaded with meaning, and inexhaustible for those trying to interpret their pages. By contrast, materialists encourage discussion between real-world people and the world being mentally sustained by the idealists. Possessed of a spontaneous philosophy, common man apparently has a certain wisdom. But Chapter 1 gives no definition of wisdom. Consequently builder Jo’s wisdom cannot be compared to that of the great teachers, or even to more modest applications of wisdom in the real world.

Althusser’s second chapter, ‘The Philosophy of Religion’, has notes on Thales, Epicurus and Plato, illustrating how religion is a longstanding subject. Not only has religion always existed in human society, it often dominates ordinary people’s personal philosophy. From this I gather that the author’s lectures of the Sixties and Seventies, on which this book is based, were well-attended by a representative selection of society eager to reveal their beliefs.

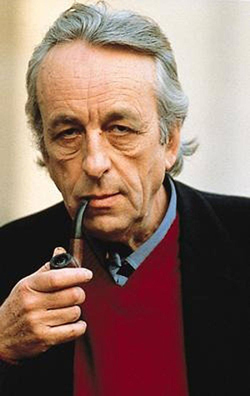

Althusser

Guidelines Althusser offers on the nature of religion are to consider it ‘an omnipotent force’ creating our world. He dismisses the question ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’ as an absurd feint, as there must be something to ask the question. Question and answer sessions in philosophy of religion do not, moreover, lift religion above the level of history and sociology. Perhaps theology is ultimately merely another heavily-laden branch on today’s flourishing social science tree.

Chapter 3, ‘Abstraction’ is the first in a set (Chapters 3 to 15) collated under the heading ‘The Big Detour’. ‘Detour’ may be an unwise analogy, given that detours can both be the result of problems and create novel unwanted, time-consuming ones. This detour is through the history of philosophy, including “philosophers farthest from us as well as closest to us.” Lest this detour isn’t sufficiently problematic, in a scant remaining one hundred and fifty pages the author has devised another simultaneous Big Detour through non-philosophy, to “analyse concrete human practices.” In ‘Abstraction’, Althusser nudges readers’ thoughts towards the weak links between words and the real or ‘concrete’ world. But he might have stressed how gaining experience of the so-called concrete world is in any case neither straightforward nor comprehensive. Unavoidably, our knowledge of that world is limited.

Chapter 20, on the class struggle, begins with “a question of the greatest importance.” Well, maybe it does. I’ve read its opening paragraph’s fourteen-line description of class ideology and philosophy as a weapon three times, yet no major question is apparent. Granted, the author’s second paragraph holds four questions: one of these might be of significant import. Further questions might also occur to readers during a perusal of Chapter 20. For instance, should a book written for non-philosophers who may be blue-collar workers, farmers, or office-workers, include phrases like “dependency on the proletariat’s political ideology in which this philosophy necessarily finds itself will not be blind servitude, but, quite the contrary, conscious determination ensured by scientific knowledge” or “If this adjective, ‘correct’, designates the effect of an adjustment that takes into account all the elements of a given situation”? Furthermore, apparently philosophy constructs ‘systems’ to force unity upon ideological elements. But does the word ‘system’ add much to this argument? It seems a soundbite, whose meaning is missing in the index. It is not obviously a purposeful whole in the manner of designed electrical systems, plumbing systems, etc.

The two short closing chapters are ‘A New Practice in Philosophy’ and ‘The Dialectic: Law or Theses?’ From these two it appears the author favours a dramatic Marxist revolution by the proletariat which eliminates class domination by battling with existing philosophy to impose a new philosophical practice. Participants in such a struggle should be wary of books which rarely hold keys to their own meaning – perhaps even including books urging revolution. Apart from those women who consider the status quo with care, for Althusser a revolutionary philosopher is a man who fights theoretically through scientific practice and ideological struggle. Oddly, an experienced life-coach or professional tutor is not highlighted for this venture.

In defence of the work, I have considered only a sample of the two hundred pages here (far less than half); the book is a translation from its original language; my command of English isn’t above average; and Louis Althusser is not alive to respond. However, interpreting the opening comment from Confucius as a warning that authors must be meticulous rather than casual, I would like to have seen an introduction which explains why the author’s structure has been chosen; sharp definitions within all sections; topics which leave readers comfortably satiated, not bloated; and content which corresponds to the book’s title.

© Neil Richardson 2018

Neil Richardson is retired from administration at North Kirklees Clinical Commissioning Group.

• Philosophy for Non-Philosophers, by Louis Althusser, trans G. M. Goshgarian, Bloomsbury Academic, 2017, 224pp, £21.99 pb, ISBN 147429927X