Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

A Moral Education

Teaching Ethics: What’s The Harm?

Patrick Stokes discusses some of the ethical problems arising in teaching ethics.

In their (not infrequent) darker moments, academics have been known to observe wryly that students’ grandparents seem to die at a much higher frequency near exams, requiring the students to have time off for the funeral. The ‘Dead Grandmother Problem’ has even been the subject of (tongue-in-cheek) academic research demonstrating that based on extension requests, the period before assessments are due is a very dangerous time for students’ relatives (see for example ‘The Dead Grandmother/Exam Syndrome and the Potential Downfall of American Society’, The Connecticut Review 7 (2), Mike Adams, 1990). This is, of course, rather unfair: students may lie to their lecturers sometimes, but people do die, and they rarely time their deaths to accommodate their relatives’ exam schedules. Moreover, as the blogger Acclimatrix has pointed out, the ‘dead grandparent’ might actually be a polite euphemism for something traumatic the student cannot (or in any case shouldn’t be expected to) disclose to their teachers. In any event, anyone who has taught a large college or university class quickly comes to realise there is a huge amount of illness, sadness, violence, disability, and loss in the background of what we see in the classroom. We only ever get glimpses of what goes on in our students’ lives, and those glimpses are often quite distressing. Imagine all the things we don’t see.

When we come into the ethics classroom, we find ourselves tasked with discussing many of the traumas that our students are dealing with outside the university. Philosophy, at its best, connects directly and meaningfully with everyday life – and everyday life can be incredibly hard to talk about, and to teach ethics is, unavoidably, to discuss topics that can be confronting and even traumatic, from matters of life and death, to more everyday problems of power and suffering. For all the talk of ‘safe spaces’ on campus, the ethics classroom must be a fairly daunting prospect for anyone who has been assaulted, lost a loved one, or ended a pregnancy, just to name a few. In one of my units, my students discuss abortion, euthanasia, sex work, and pornography – all topics that have pronounced capacities to bring up painful life experiences. Sometimes they choose to share their experiences. Just recently, in a discussion on euthanasia and the introduction of voluntary assisted dying in our state, a student mentioned that his family were very conscious of this due to his mother’s terminal illness. These can be useful moments for teaching, but they can also make the very discussion itself seem glib or crass. And for every student who shares their experiences, you can be sure there are many more who choose not to.

Another form of distress might seem harder to sympathise with but is no less real, although it is perhaps more applicable to pre-university ethics education. Part of philosophy’s particular strength is in challenging assumptions or beliefs so fundamental that they may seem unquestionable. Those beliefs can also be constitutive of our conception of who we are. Our moral beliefs in particular are intrinsic to our sense of our value as persons, in a way other forms of knowledge are not. Learn that you’ve been wrong or deeply confused about a scientific question, and you’ll perhaps feel sheepish; learn that your moral beliefs are confused, contradict each other, or cannot be defended, and you’ll be confronted with the additional question of whether you’re a terrible person. Philosophers, accustomed to suspending their beliefs for the sake of argument, can forget how distressing it can be to see the foundation of long-cherished assumptions thrown into question like that. Several years ago a colleague of mine found himself teaching philosophy of religion at a public university with a very devout student body. Some of his students complained that in merely raising the arguments for and against the existence of God he was somehow trying to take their faith away from them. They saw the very neutrality of philosophy as a threat. It’s not hard to see how ethical discussions can have the same effect.

None of this, of course, entails that we should shy away from difficult ethical topics. Indeed, what makes these topics sensitive is precisely what makes them important: they connect with questions each of us faces about life, death, love, sex, and power. As Plato has Socrates remind us in the Republic, “These are no small matters we are discussing, but how we are to live.” Ethical reasoning is a more-or-less unavoidable part of life, and as philosophers we would likely insist that equipping students to deal critically and competently with moral issues is vital for personal thriving and informed citizenship.

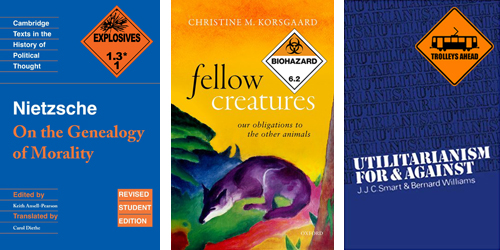

Should ethics books come with a warning?

Biohazard Placard © Losmurfs, Wikimedia. CC-BY-SA 3.0

Ethically Evaluating Ethics Education

Yet teaching ethics is a human practice like any other. We do not explore the realm of the ethical from outside that realm, in some suspended domain of pure ideas, disconnected from the lives of the participants. The ethics classroom is part of real life. And insofar as we’re talking about a real-world practice, we can evaluate that practice ethically as we would any other. It would be perverse to exempt teaching ethics in particular from ethical evaluation. This means confronting some potentially difficult questions: What harms – actual or potential – are associated with teaching ethics? And how much harm are we prepared to accept? ‘Is teaching ethics worth the risks?’ is itself an ethical question that needs to be addressed before we even enter the ethics classroom.

The question of harm is essentially an empirical one, so to answer it, we would need to call in psychologists to measure the distress caused by ethics education. Professional philosophers aren’t always very good at dealing with this kind of involvement of outsiders in their field. But let’s suppose for the sake of argument that the answer is roughly where I suspect most of us would assume it to be: that teaching ethics causes some discomfort, and very occasionally, distress. So there’s some harm, but it’s not disastrous. Nonetheless, we’re still obligated to take that harm seriously, and to work out what degree of harm is and isn’t acceptable for the benefits created.

This is where we run into a very familiar – if now amusingly recursive – problem: the lack of an agreed ethical framework through which to assess ethics education. Ethics educators typically assume that our role is not to indoctrinate students into any particular ethical view, but to teach them how to assess and critique a range of views for themselves. We don’t go into the classroom wanting to churn out a new crop of utilitarians or shoehorn our students into deontology according to our own beliefs. Most of us would rather a student disagree with us vehemently but rigorously than thoughtlessly agree with whatever they take to be our view. But when we’re assessing the practice of ethical education itself, neutrality on the type of ethics to use is going to present a problem. Accordingly, ‘Is teaching ethics worth the risk?’ is a question that may well have as many answers as there are ethicists. Yet I suspect most will alight on some version of ‘Yes’. On a utilitarian calculus, trading minor, transient discomfort for the benefits of creating an ethically literate and capable population is a no-brainer. A deontologist (= advocate of duty ethics) might argue that the teacher, in aiming to teach instead of aiming to harm, does nothing wrong if she inadvertently causes unavoidable harms while pursuing the goal of teaching. A virtue ethicist of a particularly Aristotelian stripe might claim that the teacher does nothing wrong in pursuing the good of education, so long as they avoid both callousness and timidity in how they discuss the issues.

But the discomforts may not be all that minor, nor all that transient. That suggests that ethics educators have a duty as far as practically possible to be aware of the risks, and to ameliorate them whenever possible, consistent with teaching aims. What steps might ethics educators take to this end?

For one thing, we should take seriously the notion of informed consent. Here philosophers such as L.A. Paul have noted that there are distinctive problems of being informed around choosing to undergo what she calls ‘transformative experiences’ – experiences where we cannot beforehand imagine what we will be like after the experience. Take the decision to become a parent, for instance: we’re told beforehand that parenthood will change us in ways we can’t imagine. This raises the question of how we could rationally choose to undergo it. If we take it that ethics is integral to our sense of who we are, and if it’s true, as educators believe (or perhaps simply hope), that ethics education can change people’s ethical views and understanding, then it follows that to some degree ethics education is a transformative experience. That being the case, we should at least let students know –in the same way that we try to let prospective parents know – that the experience may not leave them unaltered.

At university level at least, philosophy students generally have a fair idea what they’re getting themselves into; but flagging that a unit may challenge their fundamental beliefs won’t hurt, and may even serve to make ethics more attractive. Part of the task of the educator is to determine what students need to learn, as more or less by definition, students cannot know ahead of time what they need to know. But if students are made aware in advance that they will be challenged in particular ways, they can consent to, and become partners in, this process. That may involve the use of the infamous ‘trigger warning’ that the expression of some views might upset some students. ‘Trigger warning’ has become almost a term of abuse, and like any other educational tool, trigger warnings are open to over-use or misinterpretation. Yet warning students ahead of time that potentially distressing material is coming up is really just common courtesy. Doing so allows students with traumatic histories to manage their exposure to material that will cause them pain. Done properly, this needn’t be inimical to good teaching. Rather, it can be seen as a way of avoiding outcomes that would make learning next to impossible.

Nobody thinks ethics teachers should wrap their students up in cotton wool or duck necessary but uncomfortable conversations. But if ethics education really is as powerful as we say it is, we should handle it with care.

© Patrick Stokes 2019

Patrick Stokes is Associate Professor in Philosophy at Deakin University, Melbourne.