Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Is Attributing Evil a Cognitive Bias?

Aner Govrin argues that a common perception of evil is mistaken.

Why do we still use the term ‘evil’? Why don’t we merely say ‘very, very bad’, or ‘a severe moral failure’? I think ‘evil’ describes a category of moral failures of a certain kind better than any other word. The question I want to look at now is how we determine those kinds of moral failure.

For thousands of years, the concept of evil was closely linked to a religious view of life. In Judaism and Christianity, evil in human conduct (which is known specifically as ‘moral evil’) is viewed as extreme defiance of God’s commandments. An act of evil radically violates that holy code. However, despite the evident religious connotations attached to the concept, widespread use of the term has survived in today’s secular society. People in the West still employ the term in a variety of contexts. ‘Evil’ is used to describe war crimes, horrific acts of murder, cruelty, violence, sexual abuse, and attempts to cause suffering simply to gain pleasure from a victim’s distress.

One must assume that the concept has survived because people still find it useful. And yet, although the term is quite common, psychologists (and I am one) have usually refrained from dealing with the subject of evil. In the professional discourse, evil has been consistently viewed as at best an elusive topic, and at worst a dangerous one. The handful of academic studies that relate to evil are interested in exploring the psychology of evildoers, but the properties that guide us in recognizing evil and distinguishing it from ordinary wrongdoing remain a puzzle.

My main thesis is that moral evil is unique because it implies a unique way of thinking on the part of the perpetrator of evil toward his victim. Based on examples from the common use of the word and from my research on the topic, I have found four co-occurring features to be the most salient aspects of the prototype of evil. I want to briefly consider these features, and then explain why perceiving an act as evil is based on an attribution error. Still, we need not fix this error, because making it is important for our survival.

Four Perceived Features of Moral Evil

First, in acts that are perceived as evil there is an extreme asymmetry between victim and perpetrator. Think of the following pairs: rapist/victim; child molester/child; Nazi soldier/Jewish civilian. One feature common to most evil crimes is an extreme gap in power relations between victim and perpetrator. When an observer identifies evil, the victim is perceived as comparatively weak, helpless, defenseless, needy, and, at times, innocent.

Second, there’s a perceived lack of emotional connection between the perpetrator and the victim’s vulnerability. The observer’s impression is that the perpetrator clearly recognizes a weak and helpless person or group, and that the aggressor acts in full awareness of the victim’s vulnerability. But while in the observer this vulnerability and weakness usually arouse empathy and a desire to come to the victim’s defense, the aggressor’s perceived feelings are assumed to be very different. From the observer’s perspective, the victim’s vulnerability either fails to arouse the aggressor’s concern, or even motivates the attack.

The third feature is the observer’s inability to identify with the perpetrator’s perspective. The observer might find psychological motives which explain the aggressor’s behavior. However, his or her sense of bafflement remains, since explanation and understanding are not the same thing. Indeed, there is much debate within philosophy and psychology regarding their differences. Often in cases of the perpetration of evil, the motives remain external to the observer in the sense that even when they are known, they do not resolve the mystery surrounding the transgressor’s actions. We are unable to perceive a connection between how we think and act, and this particular terrible deed.

Fourth, what might intensify the observer’s horror is an insuperable difference between the observer’s and perpetrator’s judgment following the incident, as indicated by the perpetrator’s lack of remorse. If anything can alter the observer’s moral judgment of the case (which is not at all certain) it can only happen through the aggressor coming to perceive the situation in much the same way as the observer does – with the same degree of horror, and the same level of incredulity in the face of the violation of normal human expectations. When the perpetrator lacks remorse and regret after the act, or refuses to accept responsibility for it, the observer finds himself emotionally shaken by the way the aggressor does not perceive his own moral failure.

For some, these four features may be present in every attribution of evil within a perpetrator/victim relationship, from rape, murder, pedophilia or genocide, to merely taking pleasure in the victim’s suffering after humiliating them in public. (A person who takes pleasure in the suffering of others will be judged evil even if he was not responsible for the victim’s suffering.)

To illustrate these features working together, let’s take an example. Gabriel, a sports teacher in a school, takes pleasure in repeatedly instructing Raphael, a six-year-old overweight kid, to jump over a bar, merely in order to see Raphael failing to do so over and over again – to the great amusement of himself and of other pupils. All the salient features of the prototype of evil are present here: an extreme asymmetry in power between victim and perpetrator; an observer might naturally think that Raphael’s vulnerability triggers the teacher’s cruelty; it is almost impossible for the observer to take Gabriel’s perspective on the situation; and if Gabriel were for instance to blame Raphael after being confronted with his own moral failure, the observer will experience a second shock, and his rage toward Gabriel will intensify.

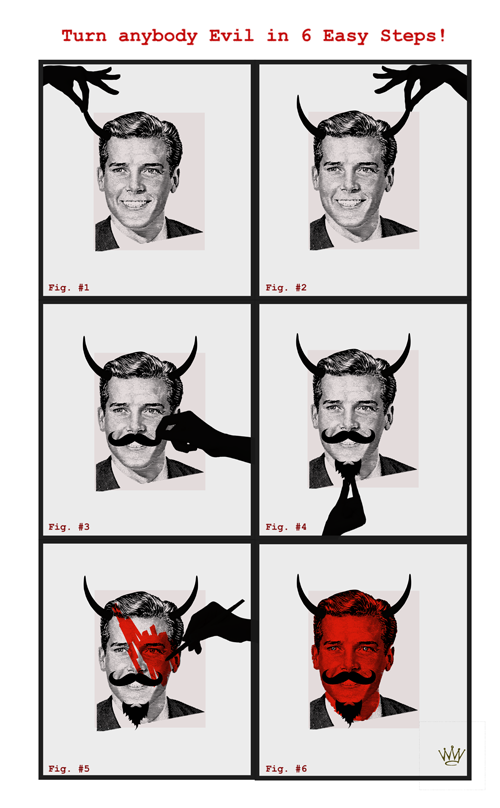

Evil graphic © Woodrow Cowher 2019. Please visit deviantart.com/woodrawspictures

Problems With These Aspects

If this analysis is correct, it means that moral evil is not fundamentally in the act itself, nor in the gravity of the damage done, but is to be found in the nature of the relationship of the aggressor to the victim in their vulnerability and weakness, or towards those who are needy and dependent in general. These are the acts that we see as evil. But are we right to do so? I suggest instead that each attribution is false, or at least not necessary for an act to be evil, and that the attribution relies on cognitive bias.

This bias can be seen in all four criteria. The relations of the Nazis to the Jews can clearly demonstrate this. (Please note that many of these factors are connected.)

First, asymmetry. The Germans experienced their defeat in World War I as a great disgrace. The Versailles peace treaty forced on Germany huge reparations, permitted Germany only a very small military force, and took away lands. After the war German citizens suffered from continuing poverty and worsening economic conditions. The defeat was widely seen as the result of betrayal by communists and Jews (this is called the ‘stab in the back’ legend). Germans who supported the Nazi Party did not experience themselves as strong and powerful and generally did not perceive Jews as weak and helpless. On the contrary, they thought the Jews were too powerful, dangerous, and threatened the safety of the German people.

An observer errs if he assumes that the perpetrator sees the same relatively powerless victim he does. Whereas the observer perceives the victim as needy, weak, and helpless, the perpetrator often sees something very different.

Secondly, linked with that idea, studies have found that in severe cases of criminality perpetrators often believe that their conduct was justified in response to what they perceived as an act of aggression by their victim. From the observer’s perspective, the Nazis must have acted in full awareness of the Jews’ vulnerability; but from the Nazi perspective the Jews were not vulnerable. In fact, many Germans saw themselves as victims of Jews, not the other way around. Similarily, sadistic people have often themselves experienced severe abuse in their childhood, and it is likely that they perceive themselves as victims of others. Raphael did not provoke Gabriel in any way, we may suppose; but perhaps Gabriel the sadistic sports teacher feels continually put upon and disrespected by those around him, and somehow has the illusion that poor Raphael is connected with his oppressors. His abuse of Raphael is his way of reasserting control (see Cracking Up, Christopher Bollas, 1995, p.170).

Third, the sheer incomprehensibility of the Nazi actions – the fact that the Holocaust seems to the observer senseless and arbitrary – shows the observer’s limited capacity to understand the Nazi mind. Many books explain the Nazis’ motives and cruelty, but (thankfully) they can’t make readers take the perspective of the Nazis or identify with their motives. However, perpetrators often believe that they have good reasons to act in what others think of as an evil way, and the Nazis were no exception. Moreover, the people who took part in that genocide were mostly normal by standard criteria of psychological health. In-depth interviews and psychological testing revealed no sign of psychological disturbance.

Fourth, after the evil act, an observer might hope that the perpetrator will undergo a radical transformation, recognizing at last the harm he inflicted through the victim’s suffering or death. Sometimes this might happen, but in many cases the perpetrator simply continues to blame the victim, or anyway to minimize his own responsibility. Such was the ‘just following orders’ argument of Nazi leaders like Eichmann in their war crimes trials. The convicted Nazis remained loyal to their past actions, often to their hatred for the victims, and refused to acquiesce to the observer’s perception of the horror. Unfortunately, the observer’s expectation of repentance is motivated not by rationally-justified hopes, but by their need to alleviate their shock and horror by finding some recognition within the perpetrator of the horrendous nature of their acts. The observer hopes that such recognition might help restore their trust in the world and in humanity.

These four misplaced perceptions support the idea that what I’ve been calling the standard perception of evil was favored by natural selection over an accurate and objective perception of perpetrators. In other words, it’s an evolved cognitive bias. However, like many other such cognitive biases, the way of looking at evil embodied in those four perceived aspects is not a design flaw, but rather a positive design feature of our minds. In terms of our own survival we are fortunate to err in this way. If people were to perceive evildoers in a more ‘objective’ way – by taking the perpetrator’s perspective into account, for example – they would probably be in danger. More than anything, the perception of evil involves fear: it signals a potential threat to the individual or their society. This fear would arguably be lessened if we were to see things the way the perpetrator does; it would weaken our defences.

That said, the usual perception of evil is also not without its dangers. Behind the most horrific violence people have inflicted on each other there was a claim by the aggressor that the victims deserved their fate because of their own wickedness. In the years before the Holocaust, the Nazi campaign of incitement painted Jews as evil, and as enemies of the German nation. So the normal perception of evil, so crucial to maintaining the stability and security of society, has also contributed to humanity’s worst crimes.

© Dr Aner Govrin 2019

Aner Govrin is a psychoanalyst and philosopher at Bar-Ilan University, Israel, and the author of Ethics and Attachment: How We Make Moral Judgments (Routledge, 2019).