Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Social Distancing in Solitude

J.R. Davis asks what Thoreau’s experience of isolation can teach us.

What might philosophy have to say about social distancing – and, for some, complete social isolation? Here it may be useful for us to reflect on Henry David Thoreau’s experience as described in his book Walden (1854), which details his own time of self-isolation.

Walden is a unique utopian account about simple living. It is not easily categorized: ‘a social experiment’; ‘a journey of spiritual discovery’; ‘a manual of self-reliance’ – many different epithets have been attached to the work to describe it. Some also criticize it, perhaps rightly, as being overly idealistic. But we might at least say that it describes an application of Transcendentalist philosophy. Walden is quintessentially Transcendentalist. Set in the backwoods of Massachusetts, it teaches us both how to live deliberately and how to be alone with ourselves: how to embrace solitude without feeling lonely. Solitude is a good, and very different from loneliness.

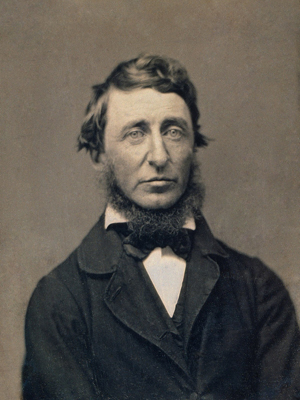

Henry David Thoreau by Benjamin D. Maxem

Thoreau and his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson were the two most notable figures of Transcendentalism. This was an intellectual movement in early nineteenth century America, intent on positively rethinking contemporary society, transforming culture from unreflective conformity to a purified individualism. It sprouted from English and German Romanticism, and was arguably the first Western philosophy since the ancient Greeks to be directly influenced by Eastern philosophy, such as the Hindu Upanishads. In Walden, Thoreau often quotes Confucius, whose translated works had just reached America. Unlike much Western philosophy, Transcendentalism’s modus operandi was intuition, not reason. But in a sense, I think Transcendentalism was also an early form of Critical Theory – a rationalist critique of contemporary society rooted in individual progress.

Like Existentialism, Transcendentalism was never systemized into a formal school of thought. Some of its concepts remain as amorphous as Heidegger’s Dasein. But unlike Existentialism, it propounded a somewhat naïve optimism towards humanity. Transcendentalism’s philosophical influence on other thinking is latent, if under-appreciated. Friedrich Nietzsche, for example, admired aspects of it. Nietzsche is ripe with trenchant criticisms of modern philosophers, save one – Ralph Waldo Emerson, the father of Transcendentalism. He loved Emerson. In 1884, Nietzsche (in The Gay Science) described Emerson’s Transcendental thoughts as being “the richest in ideas in this century.” But you may be wondering what a nineteenth century philosophy such as Transcendentalism can offer us for our challenging times.

An Experiment In Isolation

In 1845, Thoreau set out on a unique experiment – to live alone in a cabin he built near Walden Pond, in woodlands owned by Emerson. Thoreau’s ultimate purpose was to see if he could live a deliberate and fulfilling life with the mere essentials, solely relying on the fruit of his own labors, shedding the unnecessary surplus of modern existence, even as it was then. “I lived alone, in the woods, a mile from any neighbor,” Thoreau begins Walden, “in a house which I had built myself, on the shore of Walden Pond, in Concord, Massachusetts, and earned my living by the labor of my hands only. I lived there two years and two months.” So starts Thoreau’s reflexive and reflective journal on simple living in nature.

Living need not be complicated, according to Thoreau, and much unhappiness is wrought from the burdens of modern society. He writes, “Most men, even in this comparatively free country, through mere ignorance and mistake, are so occupied with the fictitious cares and superfluous lay coarse labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them.” He has a point here. I’m sure I’m not the only one who stresses out during tax season every year – another burden of modern society.

What strikes many readers, and even some of the people who on occasion visited Thoreau at his solitary cabin, was how he could live all by himself, devoid most times of human contact. As Thoreau writes, “My nearest neighbor is a mile distant, and no house is visible from any place but the hilltops within half a mile of my own.” He was not a natural hermit, though he found serenity in privacy. He didn’t hate the world, nor people, and he certainly didn’t make it his goal to avoid people, since he did receive visitors: “I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude; two for friendship, three for society.” But isolation didn’t bother Thoreau either. Indeed, isolation is such a compelling aspect of Thoreau’s experience that he devotes an entire section in Walden to it, titled ‘Solitude’.

Thoreau’s answer to anyone who asked him how one could bare to be alone is simple: turn inward while being in nature and you will not feel lonely: “I experienced sometimes that the most sweet and tender, the most innocent and encouraging society may be found in any natural object, even for the poor misanthrope and most melancholy man.” Nature attunes our minds to what really matters in life, he further explains. And loneliness is a creation of our own misinformed mental diversions.

Thoreau provides us with a kind of comforting perspective on loneliness, by pointing out that no matter how hard we try there will always be a chasm of consciousness between me and another person. “What sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary? I have found that no exertion of the legs can bring two minds much nearer to one another.” So we had best get acquainted with what is reachable – ourselves. We are our own best friends. In this, Thoreau is offering us advice similar to that of many modern psychologists: we should reframe our negative thoughts into positive and productive ones. As Thoreau suggests, we can reframe the crippling emotion of loneliness into self-fulfilling solitude. But he goes further in offering us another tool of the mind, very stoic in nature. We have it within ourselves, he says, to let the world (negative or positive) wash past us without affecting us; to observe the world as if having an out-of-body experience: “By a conscious effort of the mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent.” In this way Thoreau was able to overcome the pull of loneliness while in complete isolation.

Thoreau and the Transcendentalists were known for their overflowing optimism – whether practical or not. “I love to be alone,” he wrote: “I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude. We are for the most part more lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our chambers.”

Another thing we can learn from Walden during these unusual times is to live life deliberately. We must turn inward so we can understand the outward: to be introspective. To best encourage this mind-attuning, we need to get out into nature and think.

Being in nature thinking about the simple things in life – which is thinking about what makes us truly happy – will help us get through isolation. Obviously it’s a littler harder to commune with nature if we are in a lockdown in a city apartment. Many countries’ governments have issued restrictions on traveling or even walking outside. Nonetheless, to my knowledge, there was (or is) no law saying one cannot stick one’s head outside one’s window and take in a breath of fresh air. If Italians can sing songs from their windows while in lockdown, surely we can open a window and gaze at the birds.

But let’s be real here. All this Transcendentalist guru-talk is easier said than done, and there’s no distinct line distinguishing loneliness from solitude. It’s a blurred spectrum, which we can find ourselves drifting along, back and forth. Even Thoreau acknowledged this: “I have never felt lonesome, or in the least oppressed by a sense of solitude but once, and that was a few weeks after I came to the woods, when, for an hour, I doubted if the near neighborhood of man was not essential to a serene and healthy life.” Nevertheless, it is possible to love solitude. If we understand Thoreau correctly, maybe for once, being an introvert can be more exciting than being an extrovert.

Walden Pond panorama by Brien Beattie 2005

Five Tips from Thoreau

Below I summarise five simple tips from Thoreau we can directly apply to our lives. Surely, Thoreau would approve – if not of the tips, at least for simplifying the above discourse. (Sorry, no tips on how to build a log cabin.)

1.Shed the things of modern life that stress you out, and simplify your life

Those who have read Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up are familiar with the idea of getting rid of unnecessary clutter. But instead of tidying up your closet, think about tidying up your personal life, first, by getting rid of stress. Remember, things don’t stress you out; it’s stress that stresses you out. So maybe put down Social Media for a day and practice some meditation. Being mindful is useful, too. Getting rid of actual things can also be beneficial to your wellbeing. Do you really need subscriptions to five different streaming platforms? Or if you still have a cable box, definitely think about shedding that. Again, as Thoreau pointed out in Walden :

“Most men, even in this comparatively free country, through mere ignorance and mistake, are so occupied with the fictitious cares and superfluous lay coarse labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them.”

2. Live deliberately

As I mentioned, Thoreau’s ultimate purpose as described in Walden was to see if he could deliberately live a fulfilling life with the mere essentials, shedding the unnecessary surplus of modern life. Living need not be complicated if one lives deliberately, according to Thoreau.

How to live deliberately may be a little bit more difficult. Fortunately, Thoreau offers us some advice here – to reframe our negative thoughts and let the world wash past us without affecting us:

“By a conscious effort of the mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent.”

In this way we can help ourselves overcome the pull of loneliness even while in isolation.

3. Turn inward so you can understand the outward

This third tip stems from the second. It may be difficult to make sense of what is happening around us. For some during the COVID crisis the anxiety and fear has been palpable.

Before we can understand the world, we must first understand ourselves. This is what Thoreau endeavoured to achieve. And while many of us sit at home, trying to figure out what to do, instead of looking out there to the world to extinguish our boredom, turn inward and know yourself. Most times, when you understand yourself and truly come to know who you are, why you think how you think or why you like what you like, thinking can be the impetus for you starting a new and exciting hobby or learning a new skill. So rather than lamenting, take in a breath of fresh air instead, and reflect happily on your life and what you love to do. Start a journal, or plan your future. Normalcy will come back, be happy. Let yourself be optimistic:

“I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude; two for friendship, three for society.”

4. Get into nature

Communing with nature attunes our minds to what really matters in life. Being in nature and thinking about the simple things in life – thinking about what makes us truly happy – that will help us get through self-isolation:

“I experienced sometimes that the most sweet and tender, the most innocent and encouraging society may be found in any natural object, even for the poor misanthrope and most melancholy man.”

Going outside may still not be possible where you live. But that’s okay: you can still see the sky outside your window, and open it to breathe in the air.

5. Transform loneliness into solitude

What strikes many readers of Walden is how Thoreau could live without actively seeking human contact. But his solitude was a choice:

“I love to be alone. I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.”

But how can we transform isolation into positive solitude? That positive feeling we get when we finish a project all on our own, whether building something or putting something together in some other way, is one way that solitude can have a beneficial effect on our mental health. What we can do while isolated, is set out on our individual project. Whether it’s putting a model plane together or building a website, we can transform feelings of loneliness into fulfilling solitude when we engage with ourselves on projects we value. Thoreau took great pride in how he built his own house near Walden Pond – with his own bare hands, all by himself.

As for me, I’ll heed Thoreau’s example. My wife has me planting a garden in the backyard. I want to grow watermelons. That seems fulfilling.

Gardening may not be as ambitious as building a log cabin near a pond in the middle of nowhere, but at least I’ll be one with nature, lost in my mind.

© J.R. Davis 2020

J.R. Davis is a public affairs professional and manager in the US Air Force, living in the backwoods of South Carolina where he likes to garden with his wife. He’d like to dedicate this article to his family and his Airmen.