Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Fiction

The Power of Argument

Meriel Patrick conducts an infinitely long train of thought.

The railway is the first thing you notice when you arrive. It trundles on incessantly, weaving its way around the island, never stopping, day or night. We stand watching it for a few minutes. There’s something hypnotic about the endless line of carriages slowly rumbling past. “Come on,” says my guide at last. “There’s a lot to see!”

Her name is Davina, but she tells me to call her Vee. “There were five Davinas in my class at school,” she explains. “So we also had a Dee, and a Davie, and a Vina. It was even worse for the boys – eight Davids. They mostly went by middle names.”

We climb the stairs of the nearest footbridge. These are positioned every few hundred metres along the track.

“Where’s the station?” I ask.

“Station?” Vee sounds surprised. “Why would we need stations? Stations are for trains that stop.”

From the top of the footbridge, I can see that there are actually two trains, running side by side – an outer one going clockwise, and an inner anti-clockwise. It makes me feel slightly dizzy.

We walk down the steps on the other side. Vee suggests we take the anti-clockwise train into Humburgh. I’ve only ever seen the name written down before, so I’m glad to hear her pronunciation (Hyoom-borough) before I embarrass myself by getting it wrong.

Beside the track, the ground is paved with the sort of rubberized tiles you find in children’s playgrounds and outside pubs. I eye them warily. “Are there many accidents?” I ask.

Vee shrugs. “Hardly any. The odd scuffed knee or twisted ankle. Mostly visitors or kids. The rest of us are used to it.”

She talks me through getting onto the train: “It easiest if you walk alongside for a little while – match the pace of the train as closely as you can” – this seems doable: it doesn’t travel at more than a brisk walking pace – “then just step on diagonally. It’s honestly no harder than getting on an escalator, or a paternoster lift.”

“I imagine you’ve got plenty of those,” I say.

“Of course,” Vee says, with a smile. “Now, I’ll go first so you can see how it’s done. You follow when you’re ready.”

She moves to the track-side, takes half a dozen swift steps parallel to the train, then in one fluid movement disappears through one of the doorways. I notice that a step juts out a few inches from each door, and that there’s a comfortingly solid-looking handle to grab onto.

I wait for another door to reach me, and attempt to replicate Vee’s movements. At the last moment I lose my nerve, and instead of stepping onto the train, I land slightly awkwardly back on the rubberized paving. I’m not really hurt, but I begin to understand why twisted ankles are a risk.

Soon I try again. This time I walk a little faster, grasp the handle by the next door that comes along, and hoist myself aboard. I’ve done it!

I can see Vee waiting for me in the carriage ahead, so I go through the door and join her.

“There,” she says, “that wasn’t so bad, was it?”

Apart from the two of us, the carriage is empty. This is one of the many advantages of a train which is almost fifteen miles long: no overcrowding.

In case we should be in danger of forgetting any of the other advantages, the walls are adorned with posters. At the end of the carriage is an engraving of the great man himself – the one without whom none of this would have been possible. Extracts from his work are written in gold calligraphy above the windows.

“I’m still not sure I quite understand all this,” I say.

Vee looks pleased – I have a feeling she enjoys explaining things. “I’m sure you know that it all started with David Hume,” she says, with a nod towards the engraving. “His Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion have always been important for the philosophy of religion. But it was only a few decades ago that a research fellow at the university here realized that Hume’s ideas might have a more practical application.”

“It’s all to do with infinite sequences of events, isn’t it?” I say. I don’t want her to think I haven’t done my homework.

She nods, and gestures towards the gold lettering. “The key passage is right there.”

I read the quote aloud: “In tracing an eternal succession of objects, it seems absurd to enquire for a general cause or first author… each part is caused by that which preceded it, and causes that which succeeds it. Where then is the difficulty? But the Whole, you say, wants a cause. I answer, that the uniting of these parts into a whole, like the uniting of several distinct counties into one kingdom, or several distinct members into one body, is performed merely by an arbitrary act of the mind, and has no influence on the nature of things. Did I show you the particular causes of each individual in a collection of twenty particles of matter, I should think it very unreasonable, should you afterwards ask me, what was the cause of the whole twenty. That is sufficiently explained in explaining the cause of the parts.”

“So, basically,” Vee explains, “Hume is saying that it doesn’t make sense to ask for an overall cause of an infinite sequence. As long as each item in the sequence is explained by the one that goes before it, that’s all you need.”

“Right…” I say, not totally convinced. “But wasn’t he talking about explaining the existence of the universe? What’s that got to do with trains?”

Vee grins. “That’s the clever part. The research fellow I mentioned – Brown was his name – realized that you could apply the same logic to motion, and that by doing so you could have an infinitely long chain of carriages each of which was pulled by the one in front!”

“But what keeps the whole train moving?”

Vee’s grin vanishes. “Weren’t you listening?” she says, a trifle tetchily. “Hume showed us that you don’t need a cause for the movement of the whole thing, as long as you’ve explained what keeps each carriage moving. And we’ve done that: each carriage is pulled by the one in front. And since it’s an infinite sequence, there’s no first carriage to worry about.”

“But you can’t build an infinitely long train!” I reason.

“Of course not. So for twenty years or so, the idea remained just a thought experiment – a footnote in an article in a philosophy journal.”

“What happened then?”

“Just before he retired, Brown had a brainwave. You can’t build an infinitely long train, he reasoned; but you can build one with no first carriage – simply by looping the train round and joining it in a circle! He found an engineer who was willing to work with him, then some investors, and – well, the rest is history. Even if they don’t fully understand the theory behind it, there can’t be many people on Earth who don’t know about the railway – or about how prosperous the island has become as a result. The railway was only the start, of course: the engineers soon realized that the same principle could provide a source of free, clean power for factories, and it wasn’t long before we became the manufacturing centre of the region.. We even have some philosophers trying to apply Hume’s ideas to farming,” Vee tells me. “An infinite sequence of events that somehow generated food could solve world hunger at a stroke. They haven’t quite managed that one yet, though.”

We’re now approaching Humburgh. It’s in fact a smallish town, but the skyline is truly impressive – it has skyscrapers that wouldn’t look out of place in a major metropolis. “Very low building costs,” Vee explains, nodding towards them. “All the cranes are powered by the infinite loop principle.”

Once we reach the town centre, Vee steps onto the rubberized platform without a second thought. It takes me a few moments to pluck up the courage, but I manage it eventually. “You’ll be hopping on and off like a local by the end of the day,” Vee assures me.

She wants to show me the old town, so we walk in that direction. As we do, a thought that has been niggling at the back of my mind since the train journey starts to coalesce. “I just don’t see that it makes sense,” I say.

“What do you mean?”

Vee looks uneasy. I continue: “I mean all this business about not needing a cause for the movement of the whole as long as you’ve got a cause for the movement of each part. I mean, imagine if you had a book – a volume of philosophy, say – where the content had been copied from an earlier edition. If someone tried to tell you that the earlier edition had been copied from a still earlier one, and so on and so on forever, that wouldn’t mean there was no need for someone to have actually written the text –”

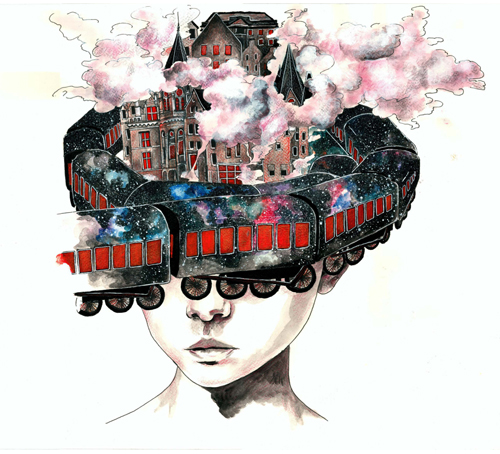

© Cecilia Mou 2020. See more of her art on Instagram: @mouceciliaart

Vee grabs me by the elbow and yanks me down a side street. “What the hell do you think you’re doing?!” she hisses.

“Look, all I’m saying is that –”

“Well, you can’t say things like that here!” She seems frantic. “Didn’t you see who was behind us?”

I shake my head, and rub my arm. After a few moments, a scholarly-looking couple in academic gowns strolls past the end of the alleyway. The woman’s voice floats towards us: “But you have to take into account what Plato said in the Republic…”

Once they’ve gone, Vee lets out a deep sigh of relief.

“Who were they?” I ask.

“The thought police,” says Vee. “You don’t know how close you came to getting taken in for questioning. Oh, it might all have been tea and scones and even a glass of sherry at first, but if you hadn’t been extremely careful you might easily have ended up being viva-ed.” She shudders.

“I don’t understand,” I say. “I would have thought somewhere like Humburgh would have been all in favour of free speech.”

“It depends what you mean by free speech,” Vee says. “Politics, religion, morality, the best way to educate children – you can say whatever you like about that sort of thing. But can you imagine what would happen to the island if anyone ever proved Hume wrong about infinite sequences?”

I think about that for a moment.

Vee continues, “There was enough trouble a few years back when someone proved that centrifugal force didn’t really exist, and all the salad spinners stopped working… And the honey industry is still recovering from that business about whether or not bees should be able to fly. You just can’t take chances with this sort of thing. It’s practically terrorism. Or take Hume’s writings about the nature of causation, for example – imagine if someone followed up on those and proved conclusively that there’s no relation between cause and effect.”

It’s not a pleasant prospect.

Vee takes a few deep breaths, obviously making a conscious effort to calm herself down. “You seem to have got away with it this time. The thought police didn’t hear you, and everything’s still working.” I can hear the distant rattle of the railway, and the hum of the machinery in a nearby factory.

Vee pats the wall of the building next to us. “The stone probably helped.”

“The stone?”

“Yes. No one’s really sure why, but for some reason being surrounded by stone seems to damp down the effect of controversial ideas. Think about it… People say all sorts of things in parliament, or in churches, or in universities, and it never seems to have quite the effect one might expect.”

I nod. “I’ve never thought of it before, but it makes sense,” I say.

“ Hmmm … I think perhaps we should get you underground for a bit. No sense taking unnecessary risks.” She takes my arm again – a little more gently this time – and walks us briskly through the streets. We come to an imposing square surrounded by attractive grey stone buildings. I recognize the largest of them as Humburgh’s university.

There are a lot of people in the square – a bigger crowd than I’ve previously seen anywhere on the island. A gaggle of skinny bottle-blonde girls teeter past us on impossibly high heels. Three of them are having an energetic discussion about the relative merits of magenta and fuchsia nail polish, while another is saying loudly into her phone, “And I was, like, totally, but she was like, no way!” They’re not quite what I expected in the citizens of a place like Humburgh. I say as much to Vee.

“They’re buffers,” she says. “I expect there’s just been a shift change.”

I think we’re going to the university; but at the last minute Vee steers me off to the left and through a heavy oaken door. I can see that the walls of the building we’ve just entered are at least a foot thick.

We cross a hallway, and go down a flight of stairs at the far end, into a large chamber furnished like a sort of common room – chairs and sofas grouped around coffee tables, a television warbling away to itself in a corner, and a bar serving drinks and snacks. As we move through the room, we pass more girls dressed up like the ones we met in the square; several teenagers who are glued to repetitive games on their phones; and a group of blokes discussing conspiracy theories.

“Here we go,” says Vee, taking a free seat and gesturing me towards another. “You can say whatever you like in here.”

I look around in bewilderment. “Is this some kind of secret den for free thinkers?” The company doesn’t seem particularly promising from that perspective.

Vee snorts with laughter. “Not quite,” she says. “It’s a damping zone – a government run facility. Anyone who finds themselves bothered by dangerous ideas can come here. An hour or two with this lot is usually enough to jam anyone’s ability to think about anything much; and there’s more than enough background silliness here to drown out any rogue thoughts that do escape.”

“Oh,” I say. “I’m surprised it’s so near the university. I wouldn’t have thought the dons would be very impressed by that sort of thing.” I nod in the direction of two young men who are deriving enormous amusement from their ability to make rude noises.

“The university couldn’t function without it,” Vee tells me. “They can’t do their job without the risk of dangerous ideas arising, so it’s essential that there’s somewhere like this where students, and dons, can come when they need to.”

“But couldn’t you just defuse anything dangerous with a thought experiment?” I ask.

Vee looks puzzled. “How do you mean?”

“Well, if someone comes up with something really outlandish, then you just tell them a story about what the world might be like if they were right. And when they see how absurd that is, they’ll realize that there must be a problem with their argument.”

Vee ponders this for a few moments.

“Nah,” she says. “It’d never work.”

© Dr Meriel Patrick 2020

Meriel Patrick is Lecturer in Theology and Philosophy for SCIO, a visiting student programme at the University of Oxford.