Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Time, Identity & Free Will

Do We Want To Be Free?

Siobhan Lyons discovers that free will doesn’t come for free.

In the BBC America series Killing Eve, Russian assassin Villanelle breaks out of jail with another inmate. Upon exiting the escape vehicle, the inmate appears anxious, and asks: “What should I do?” Villanelle replies: “I don’t know. Run. You’re free.” But the inmate simply replies: “I don’t want to be free.” Villanelle looks understandably perplexed. She has, after all, been struggling for freedom – from police, from employers, from obligations and from circumstances – all of her life. But her inmate’s response is not all that strange. Morgan Freeman’s character Red, in The Shawshank Redemption, gives us some insight into the experience of being institutionalised: “These walls are kind of funny. First you hate ‘em, then you get used to ‘em. Enough time passes, gets so you depend on them. That’s institutionalized.”

One of the most enduring philosophical questions concerns the tension between free will and determinism. The question of whether the future is predetermined or whether we are active agents occupies the minds of philosophers, insomniacs, bank tellers, robbers, nurses and perhaps dolphins, and it remains uncertain whether or not we have any choice in thinking of such things. Red’s thoughts on being ‘institutionalised’ are important here, since the question of whether we should want freedom is so rarely asked.

The very idea of freedom is entrenched in our personal and moral codes: it is hardly controversial to say that we do not want to be bound by forces beyond our control, subservient to the whims of other people and of the universe. But the question of whether we should want freedom is so rarely asked. To question freedom itself is, for many, tantamount to insanity. Why wouldn’t we want to be free – especially when so many people have suffered the injustices of oppression, and still suffer them every day? But the desire for freedom is more than just a desire for liberty from oppression. It reflects an intuitive desire for self-determination, to be the author of one’s own life. For our lives to have meaning, the argument goes, it is necessary for us to have some control over what kind of people we are and the trajectory our lives will take. The idea that we cannot change anything also has a danger of becoming its own self-fulfilling prophesy, whereby we no longer try to change those things we perceive as inevitable.

The mathematician Edward Lorenz, on the side of free will, argues:

“What, then, should we choose to believe – that everything has been determined, or that we are free to make decisions? I believe that the appropriate answer is obvious if, like mathematicians, we introduce certain premises before attempting to reach conclusions. Let our premise be that we should believe what is true even if it hurts, rather than what is false even if that makes us happy. We must then wholeheartedly believe in free will. If free will is a reality, we shall have made the correct choice. If it is not, we shall still not have made an incorrect choice, because we shall not have made any choice at all, not having a free will to do so.”

(The Essence of Chaos, 1993, p.160).

Some see free will as an illusion. In 1814, the mathematician Pierre Simon de La Place envisaged that every atom conforms to precise mathematical laws of motion set up from the beginning of time, so that it would in principle be possible to predict the entire future of the universe. This idea has become known as scientific determinism. Paul Davies accurately describes this as a “bleak, mechanistic picture” (Chance, 2015, p.147). It would seem to discount the notion that we have anything resembling free will. But some are hesitant to claim that free will is an illusion, for reasons that go beyond simple self-image. If we have no control over events or ourselves, then we are in theory absolved of any kind of responsibility for our actions. But the denial of free will isn’t ironclad, by any means.

The Seductions of Determinism

In his 1844 book The Concept of Anxiety (originally titled The Concept of Dread), the seminal existentialist Søren Kierkegaard analysed the particular feelings associated with an awareness of freedom, arguing that “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom” (p.75). For Kierkegaard, freedom signifies a specific kind of anxiety, or dread, relating to the infinite number of possibilities presented to us by freedom. It compels dizziness. When we’re choosing what sort of milk to buy, what sort of career we might want, and to which destination we should travel, we are plagued by the burden of freedom. He wrote that “freedom now looks down into its own possibility and grabs hold of finiteness to support itself.” By this he means that we look for some way of mentally reducing the infinity of possibilities that present themselves to our choices.

Our anxiety also stems from the realisation that we have the capacity to ruin our lives by our decisions. Kierkegaard uses the Fall of Man as an example of this particular anxiety: knowing full well that he is forbidden to eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, Adam does so anyway, provoking his own downfall.

This anxiety relates to what the French call ‘ appel du vide’ – the ‘call of the void’ (nothing to do with apples). When looking down from a great height, or sitting in an exit row beside the door on a plane, some people feel the compulsion to jump or to pull the door open mid-flight, not because they are suicidal or eager to kill people, but just because they are curious about whether or not they are even capable of bringing about such an action – whether they are capable of disobeying their most primitive instincts of self-preservation and survival. This demonstrates the dizziness of freedom. They understand exactly what would happen, but they’re unsure of whether they could bring themselves to actually do it, to test the extent to which they are free. In other words, for Kierkegaard, our existential feeling of dread or anxiety is spurred by the knowledge of what we need to do to prove that we are free.

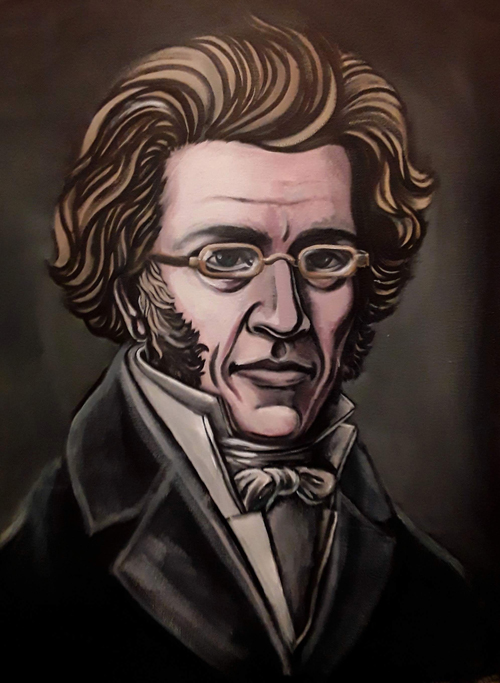

Søren Kierkegaard fretting about freedom

Portrait © Woodrow Cowher 2020. Please visit woodrawspictures.com

So for Kierkegaard, freedom is not simply a euphoric fulfilment of our autonomy. It offers a dizzying multitude of possibilities, many of which are not necessarily in our best interest. Free will suggests that we can engineer our own misfortune. The sheer enormous import of this freedom, and the infinity of choices with which we are presented has even led to the compulsion known as pathological indecision, or ‘aboulomania’. But one might think it’s hardly pathological when we think of the labyrinth of circumstances which confront us every day. When Frida Kahlo got off one bus to retrieve her lost umbrella, and then boarded a second bus, she couldn’t have known that this would mean she would be involved in a crash that would impale her pelvis and cause her pain for the rest of her life. Whether we blame the umbrella or the streetcar that collided with the second bus, it’s clear that the freedom of choice also presents us with the freedom to die, or at least to become severely injured. It’s a wonder more of us are not aboulomaniacs.

Clearly, free will signifies the freedom that we can freely make the wrong choices, and that there are indeed wrong choices to be made. This is the kind of freedom that some would eagerly exchange for a prison of determinism. It can be far more appealing to comfort ourselves with the tonic of ‘inevitability’. Here enters what Slavoj Žižek described as the ‘temptation of meaning’ that occurs when tragedy strikes. For some people, it is better to think that misfortune is some kind of cosmic punishment than to think of it as merely a random occurrence. “When something horrible happens, our spontaneous tendency is to search for a meaning. It must mean something… Even if we interpret a catastrophe as a punishment, it makes it easier, in a way, because we know it’s not just some terrifying blind force” (Examined Life: Excursions with Contemporary Thinkers, Astra Taylor, 2009, p.157). As Žižek explains, in the middle of a catastrophe, “it’s better to feel that God punished you than to feel that ‘it just happened.’ If God punished you, it’s still a universe of meaning” (p.158). If so, it’s better to think that the bus crash is what spurred Kahlo to paint while recovering rather than to think of it as a random accident. The accident, after all, derailed her plans to become a medical illustrator.

Furthermore, under determinism, not only does the murderer absolve themselves of moral responsibility, but we, too, might console ourselves with the knowledge that we aren’t successful or rich because that’s not what was ever in store for us, and we should, therefore, love our fate (Friedrich Nietzsche called that ‘ amor fati’). It’s a rather convenient way to be absolved of the pressures of choice. And although some people would never relinquish their liberty for the sake of existential comfort, there are many others who would eagerly abandon the idea of free will to subscribe to the idea that things are simply ‘meant to be’, since this dulls the agony of tragedy or bad luck. But it’s hardly a coincidence that amor fati and the ‘temptation of meaning’ both tend to arise when tragedy befalls us. We’re attracted to the idea that we had control over our successes, rather than over our failures.

Effect & Cause

For Kierkegaard, while life is lived forwards, it is only understood backwards, looking back upon our lives. Robert Pirsig made a similar claim in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974), writing: “You look at where you’re going and where you are and it never makes much sense, but then you look back at where you’ve been and a pattern seems to emerge” (p.156). Hindsight seems to matter more than foresight when it comes to deciphering the apparent chaos, whenever we begin to ask these questions, wondering whether we can perceive particular patterns in our lives, or whether it was fate, or choice, or both that brought us to where we are now.

Louise realises she’s destined to marry Jeremy Renner

In Ted Chiang’s novella Story of Your Life (1998), adapted for the screen as Arrival (2016), we are offered an intriguing take on the relationship between determinism and free will for a life. The film is also particularly effective in illustrating the ways in which we conceive of ‘past’, ‘present’ and ‘future’.

From Arrival’s opening scenes, which show linguist Louise Banks (Amy Adams) playing with her daughter, we are inclined to believe that these are flashbacks. We see Louise’s daughter become a young teenager before being struck with a rare illness that takes her young life. It isn’t until later that we discover that these are actually flashforwards – glimpses into the future – brought about by Louise’s immersion in an alien language.

The Sapir-Worph hypothesis is that the language you use determines how you conceive reality. Louise’s conception of reality changes as she thinks in the new language, so that now she perceives time in a new way. Unlike human languages, which operate sequentially (beginning, middle and end), the heptapod language is based on simultaneity, meaning that all meaning is communicated at once, and time is no longer linear, but simultaneous. The heptapod’s language rewires Louise’s brain to such an extent that she develops the ability to see her future laid out before her. She duly comes to the understanding that if she has a daughter, her daughter will die from a rare disease.

Viewers might be tempted to see this future as a bleak, entirely predetermined inevitability. Indeed, the flashforwards seem to indicate that Louise has no choice in the matter whatsoever, that her daughter will inevitably die young. But this is not the point that Chiang was interested in making. While it may seem as though Louise is simply acquiescing to the inevitable and choosing to love her fate, as Nietzsche advised, the flashforwards actually present Louise with a choice. That is to say, her knowledge of the future does not negate the fact that she has to choose; and the fact that she chooses having her daughter knowing what will happen does not invalidate the autonomy of her decision. Just because she has the option not to have a child – the freedom to do otherwise – Chiang sees Louise’s choice as admirable, even though her decision brings into effect the bleak future that was presented to her. In making her decision, Louise accepts choice within the limits of freedom, and uses it to the benefit of herself and her daughter. If we can see a future we cannot change, we can at least change how we respond to and act on this knowledge. Louise cannot alter her daughter’s fate, but she can decide how the knowledge of her daughter’s fate changes her relationship with her daughter.

The story does not abide by our normal cause and effect model, but instead supposes that future events can trigger important reverberations in the past, as odd as this might sound. In other words, the film adopts more of an ‘effect and cause’ model. The film can also be seen as an expression of compatibilism, the idea that a semblance of free will and morality exists alongside causal determinism.

Louise learns the language that loops time, in Arrival

Arrival images © Sony/Paramount pictures 2016

Out Of The Cave… & Into The Void

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1865) concludes with the phrase, “It is necessary to renounce a freedom that does not exist, and to recognize a dependence of which we are not conscious.” Daniel Dennett isn’t overly fond of this idea, arguing in Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting (2015) that the death of free will might lead to apathetic resignation in us all. Dennett nevertheless asks, “would lacking this freedom really be like being in prison, or like being a puppet?” (p.187). We certainly can’t tell if we aren’t free to choose, although we may get an inkling now and then when something happens that makes us feel powerless. In this sense we might be like the prisoners of Plato’s Cave in his Republic, convincing ourselves that we are free whilst chained, and repelling the enlightened escapee who has returned to try to convince us otherwise.

We might at least claim that we have the freedom to choose whether or not to believe we are free. We at least notice, for instance, that there is something identified as ‘determinism’, and something identified as ‘free will’ – which is more than Plato’s prisoners knew. One might even surmise that the knowledge of these two phenomena is itself evidence of some degree of freedom. Conversely, if we prisoners of causation ever come to the conclusion that we are indeed prisoners, how could we respond to this? Plato never explicitly reveals to us how his enlightened prisoner recognises his deception in the first place; rather he abjures us, “Consider, then, what would be the manner of the release and healing from these bonds. When one was freed from his fetters and compelled to stand up suddenly and turn his head around and walk and to lift up his eyes to the light.” Nevertheless, something stops us from pulling the plane door open or from jumping into the void to test our freedom: be it self-preservation, fear, or common sense. Most people, I imagine, would be unwilling to go to these lengths to prove that they are free.

We know we can choose not to open the door or jump, but we’re unsure whether we can choose to jump or open the door. This temptation is different to the temptation of which Žižek speaks, and when we think of tragedies, it becomes obvious why freedom is so terrifying. When his son’s murder case is reopened in The X-Files, agent John Doggett is uneasy, explaining: “I [must] believe that I did everything I could to save him, to get him back safe, to not let him down. I got to believe that I did everything humanly possible, ‘cause if I can’t believe that then these other possibilities that you talk about… if they’re real, then… that’s something else I could have done to save my son.”

While many philosophers are anxious about the moral consequences of a deterministic universe, freedom itself reveals to us the horrific possibility of choosing poorly rather than wisely. In a deterministic world, responsibility is a moot point. But a world defined through free will presents us with precisely too much responsibility. So freedom may, in fact, incapacitate us.

© Dr Siobhan Lyons 2020

Siobhan Lyons is a writer and scholar based in Sydney, where she earned her PhD in media and cultural studies.