Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Philosophical Haiku

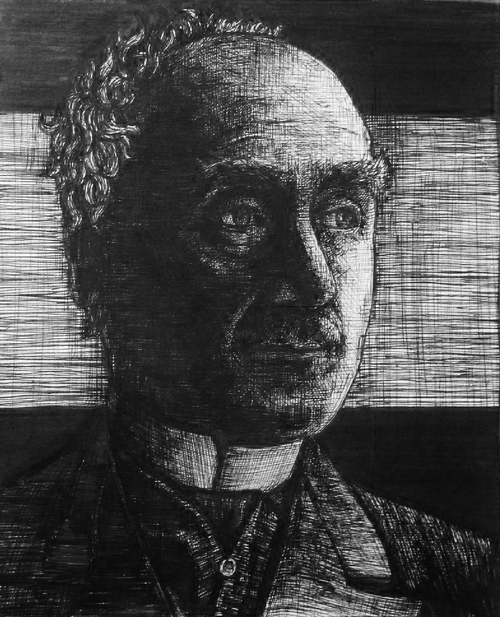

Henri Bergson (1859-1941)

by Terence Green

Creative life force

Matter mastered by élan

Onwards without end.

There have been few philosophers in history whose lectures are capable of causing traffic jams, but Henri Bergson was one.

Born in Paris to a Polish Jewish father and an English-Irish Jewish mother, he spent part of his childhood in London before the family set- tled permanently in France. Little Henri was a child prodigy, excelling in mathematics, for which he won a prize by solving a problem set by Pascal (not, in case you’re wondering, the one involving placing wagers on God’s existence). Inevitably Bergson became a professor of philosophy. Less inevitably, he married a cousin of the novelist Marcel Proust, who was the best man at the wedding (presumably he took several days to give his speech).

In 1907, Bergson published Creative Evolution, triggering what the French called ‘le Bergson boom’. Accepting the idea of evolution, Bergson rejected the idea of the random accidents of natural selection as its driving force. Instead, he argued, there is a mysterious, inherent creative drive permeating all existence, which he called the élan vital or ‘life force’. Through much struggle and ingenuity, this Force creates new life forms by conquering the resistance of matter to be organised. The élan vital is the source of human creativity also, and the spark of human genius.

Ordinary people (including people as ordinary as George Bernard Shaw) thought that this was a smashing idea, and when Bergson visited Manhattan in 1913 to give lectures on the book, his presence created the first traffic jam in history on Broadway, as people crowded to the theatre to hear him!

In 1927, Bergson was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, which perhaps best reflects the scientific standing of his speculations on evolution. Departing from the more typical philosophical concerns, Bergson also produced a philosophical inquiry into the causes of laughter, entitled Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (1900). Someone less charitable than myself might wonder if Bergson included his own evolutionary speculations among those causes.

© Terence Green 2020

Terence Green is a writer, historian and lecturer who lives in Paekakariki, New Zealand.