Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Truth by Simon Blackburn

Nick Everitt is unconvinced that what Simon Blackburn says about truth is true.

We live in an age in which truth, and our knowledge of the truth, is ridiculed – where even presidents dismiss unwelcome truths as ‘fake news’. A book on truth, then, and on areas in which truth proves elusive, by an ex-Professor of Philosophy at Cambridge, is timely.

Blackburn starts with the nature of truth itself. What is it to say that assertions, beliefs, claims, judgments, propositions, and so on, are true? One plausible answer is that a true proposition corresponds with the facts. However, this apparently common sense response has been poorly received by philosophers, who deem it to fall foul of one or other of two objections. First, what does ‘correspond with the facts’ mean or imply? If ‘corresponds with the facts’ is just a synonym for ‘is true’, then the idea provides no illumination. The other problem is that finding out the facts is itself to form our beliefs about what is true. There isn’t a twofold process, of finding out the facts, then seeing if our beliefs correspond to them, and so are true. In other words, it’s not as if we could discover a lack of correspondence between what we take the facts to be and what we believe. So, as these skeptical philosophers say, the supposed relation of correspondence is empty.

Blackburn endorses this conclusion before considering two further theories of truth – the coherentist and the pragmatist. Although he treats both sympathetically, he ultimately, and convincingly, finds that they are both inadequate. The position he favours is the so-called ‘deflationist’ account. This says that to assert a proposition P (for example, ‘It’s raining here now’), and to assert that it is true that P, amount to the same thing: both statements will be true or false under the same conditions. Similarly, to believe, hope, fear, judge, and so on that P, and to believe, hope, fear, judge, and so on that it is true that P, amount to the same thing. There may be a difference in rhetorical force between the simple assertion that P and the assertion that it is true that P, but from the point of view of truth there is no difference. To say ‘It’s true that P’ is as if one had said ‘Indeed, P’.

This suggests that to say something is ‘true’ is wholly redundant, in that it doesn’t enable us to say anything that we cannot say otherwise. Blackburn, however, does not go this far, claiming that it is useful to have a concept of truth for cases where we want to endorse the truth of some propositions but do not know exactly which propositions they are. To use his example, I might believe that ‘Everything Einstein said was true’ without knowing exactly what Einstein did say. If I don’t know what he said, then since I don’t know what the relevant propositions of Einstein’s are, I can’t use the equivalence of ‘P’ and ‘It is true that P’ to get rid of the concept of truth.

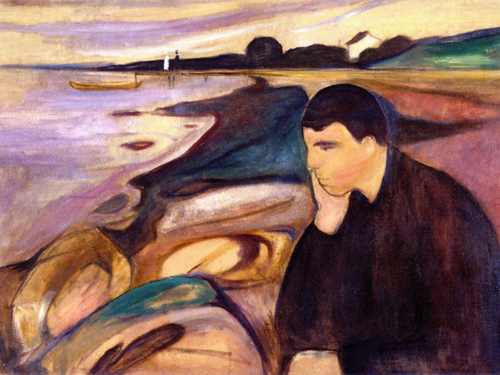

The truth about art: is this beautiful or not? Melancholy by Edvard Munch, 1894

The second part of the book discusses how we can discover the truth in three problematic areas: art and matters of taste; ethics; and religion. In all three domains, people engage in reasoning, and in doing so, they appear to be seeking truths. One would therefore expect Blackburn to discuss what the reliable sources of knowledge or reasonable belief are in these areas, perhaps looking at such candidates as experience, reasoning, testimony, experiment, intuition, and so on.

He does something surprisingly different. Consider the case of art. Art criticism clearly contains some assertions that are straightforwardly true or false – about, for example, who painted a given picture, what school the artist belonged to, whether she was the first to use a certain perspectival convention or technique, and so on. In such cases, there are experts, who know more than most people what the truth is. Blackburn rightly emphasises this, and how we can learn from people who have such knowledge. His position is less clear about the more evaluative vocabulary of criticism, concerning matters of taste, where truth does indeed seem problematic. One critic finds a painting delicately touching; another says that it is cloyingly sentimental. Can claims like this be true or false, and if so, why do disagreements about such judgements apparently survive all the relevant evidence? It would have been helpful for Blackburn to explore this issue more fully, since it in this sort of area that puzzles about truth and our access to it are most acute. Rather surprisingly, later in the book (p.112), he says that he has been ‘quite hospitable’ to the concept of aesthetic truth, but nothing in the chapter on art shows how we might access these alleged truths.

There is a different oddity in his discussion of religion. People have claimed a great many religious beliefs to be true and to be well-supported by evidence: for example, that gods exist, that miracles occur, that there is life after death, that Jesus was divine, that a god created the universe, and so on. In relation to each of these claims, sceptics have produced grounds for thinking that they are false, or at best improbable. So a serious enquirer after truth in this domain should surely attempt, if possible, to review these arguments and counterarguments for herself, and to form her own opinion about their relative strengths. However, although Blackburn devotes three pages to a summary of David Hume’s criticisms of theistic arguments, most of his discussion is not centred on the epistemology of religious belief but on the social function of religious ritual. He follows Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) in saying that “the principal function of religious practice [is] to weld numbers of people into a social whole” (p.101). Durkheim’s claim may be an interesting one. It may even be true. But it is irrelevant to questions about the truth of religious claims. Establishing that a belief does or does not have a function, and whether it successfully fulfils that function, tells us nothing about whether it is true, nor about whether we have any good grounds for accepting it.

Durkheim is followed by Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679). Blackburn quotes with apparent approval Hobbes’s view that claims that God is “good, just, holy, [and a] creator” can legitimately mean no more than an expression of “how much we admire Him, and how ready we would be to obey Him” (pp.103-4). This Hobbesian position entails that a believer apparently making assertions about God is really making assertions about herself. But he also attributes to Hobbes a rather different view – namely, that someone who makes assertions about the nature of God (for example, that he is omniscient, or loving, or omnipotent) or about the afterlife (for example, that it will be the occasion for rewarding the virtuous) is doing no more than taking up an attitude towards reality: she is not describing reality at all it, either truly or falsely. This second position entails that saying ‘God exists’ is equivalent to saying something like ‘Hurrah for God!’ Both positions are wildly implausible, and it is intriguing that Blackburn does not deal with them more robustly.

Blackburn’s discussion of truth in ethics again focuses largely on David Hume (1711-76). Hume’s strategy, he says, “is very much that of the evolutionary psychologist” (p.89), in that he seeks to understand how the institution of morality develops given a certain conception of human nature and of the world. It is because moral beliefs give rise to actions which matter to us that “we properly treat it as if there is a question of truth to be settled” (p.91). But how does the evolutionary psychological strategy yield answers concerning the alleged truth of moral claims? Take Blackburn’s own example, that stamping on babies for fun is wrong. If we ask “But is it really true that baby-stamping is wrong, rather than simply an expression of attitude?”, Blackburn will invoke the deflationary theory of truth which he accepted earlier. In other words, he will say that ‘Baby-stamping is wrong’ and ‘It is true that baby-stamping is wrong’ are equivalent. But this leaves us with some residual worries. What shows that baby-stamping is wrong, rather than simply that it’s widely believed to be wrong? And if moral claims really are true or false, why does Blackburn say that it is proper to treat them ‘as if’ they were true – the implication surely being that they aren’t really true or false?

Truth is part of the ‘Ideas in Profile’ series, and it abundantly fulfils the aim of the series, which the blurb tells us is to provide “lively incisive introductions to big topics.” It is elegantly written and enjoyable to read, and it provides a lucid conventional discussion of what truth is. But its discussion of how we can gain the truth in the three areas selected is much more controversial, and left this reader unconvinced.

© Nick Everitt 2020

Nick Everitt was Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of East Anglia. He is the author of The Non-Existence of God (Routledge).

• Truth, Simon Blackburn, Profile Books, 2017, $13 pb, 192 pages, ISBN: 1781257221