Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Further Animal Liberation

John Tamilio III augments the arguments of Peter Singer.

The work of the contemporary ethicist Peter Singer has advanced the cause of animal liberation more than any other thinker. Nigel Warburton of the Philosophy Bites podcasts calls this Australian philosopher ‘a modern day gadfly’ in the spirit of Socrates. This article will build upon Singer’s work, adding another dimension to it. Before doing so, however, let me place animal liberation in the context of other liberation movements.

A Short Survey of Liberation Movements

As the name suggests, liberation movements seek the deliverance of an oppressed group. To achieve this, liberationists often seek to expose institutional patterns of oppression constructed upon a worldview by which a privileged group justifies wielding power over another, marginalized, group. Such patterns are often precognitive: the privileged typically assume without much self-criticism that their position of power is natural. In some cases, the oppressed are dehumanized. They are then seen as things, not persons. That’s how oppressive structures survive. When brought to light, the horrific, prejudicial nature of such patterns of thought and life are exposed, which leads, ideally, to reform.

Historically, liberation movements have usually focused on human beings, with people challenging what they see as an injustice within a culture – a wrong in which one group sees itself as superior to another. Such marginalization has been based on race, class, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and a host of other categories that would seek not to be scrutinized, for scrutiny would undermine their authority. When Thomas Jefferson opened the US Declaration of Independence with the phrase “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” he meant all property-owning white men. Clearly he did not consider African slaves – some of whom he owned – to be his equals. Nor did the word ‘men’ have the archaic meaning of ‘mankind’, so as to include women, for they would not see the right to vote in the USA for another 144 years.

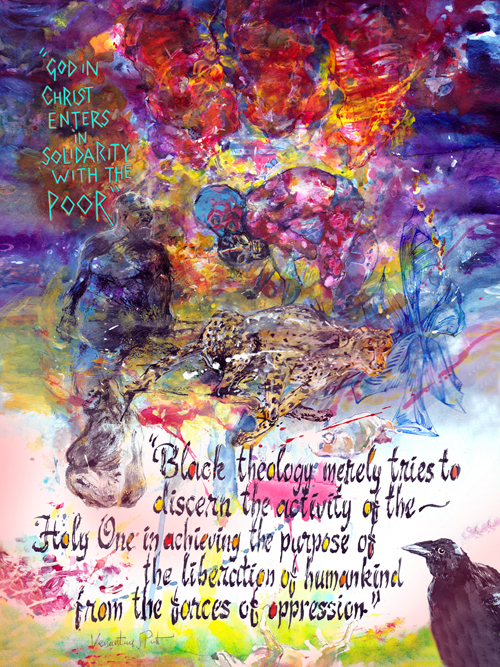

The Civil Rights Movement was itself a kind of liberation movement, but that term didn’t come into vogue until the early 1970s, and even then it wasn’t initially about the plight of black people in America. In 1971, the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez published Teología de la liberación: Perspectivas, which was released in English two years later as A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation. This groundbreaking text developed the concept of ‘liberation theology’, a phrase which Gutiérrez coined in a 1968 article (also in Spanish), ‘Toward a Theology of Liberation’. With poverty in South American particularly in mind, Gutiérrez maintained that God has a ‘preferential option’ for the poor. To fully understand the Gospels, they need to be read from the perspective of the poor and oppressed, because these are the people to whom Jesus preferentially ministered. As Daniel L. Migliore writes, “God in Christ enters into solidarity with the poor” (Faith Seeking Understanding, 3d ed., 2014, p.208). Other Latin American theologians also lent their voices to the new field: Oscar Romero, Jon Sobrino, as well as Leonardo and Clodovis Boff, to name a few. Other social activists, advocating additional ‘liberations’, quickly followed. James Cone, Professor of Systematic Theology at Union Theological Seminary, gave some initial shape to the black liberation movement. Four-and-a half decades before the emergence of the Black Lives Matter campaign, he wrote in A Black Theology of Liberation (1970), “Black theology merely tries to discern the activity of the Holy One in achieving the purpose of the liberation of humankind from the forces of oppression” (p.7). Cone’s work is quite controversial, though. In his passionate call for justice – for black self-definition free from the shackles of institutional white dominance – he condones violence.

Feminism is also a liberation movement, and it long predates the work of Gutiérrez and Cone. Some would trace it to Mary Wollstonecraft’s classic A Vindication of the Rights of Woman way back in 1792. In the US many date the origin of the women’s rights movement to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who in 1848 presented her Declaration of Sentiments at the Seneca Falls Convention in New York. This launched the women’s suffrage movement in America, leading, eventually, to the Nineteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution, giving women full voting rights. Today, the term ‘feminism’ conjures a theoretical framework that seeks to expose misogynistic aspects of Western culture, and to advocate full equality between men and women in all aspects of society.

The term ‘womanist’, coined by the novelist Alice Walker, and typically associated with writers and theologians such as bell hooks (sic), Katie G. Cannon and Emilie Townes, represents a critique of black liberation and feminism which combines both movements. Being black and female is historically doubly difficult: the person finds herself liable to a dual form of discrimination: racism and misogyny. Womanist theorists maintain that black liberationists do not take this into account, nor do feminists. The latter, they assert, are usually privileged white women, typically academics, who do not take the unique plight of their black sisters into consideration when constructing their polemics. Meanwhile, the work of the black liberationists, womanists claim, is frequently gender-biased.

There are many other liberation movements, too. Philosophers and theologians who call themselves Mujeristas are Latina feminists who focus on the plight of women in their community; gay liberation focuses on dispelling the experience of marginalization by members of the LGBTQIA+ community. But the focus of these and similar movements is to seek to expose the forms of oppression that subjugate marginalized groups of human beings. Peter Singer casts his net wider.

Image © Venantius J Pinto 2021. To see more art, please visit flickr.com/photos/venantius/albums

Singer & Utilitarianism

In 1975, Singer published the definitive classic of the animal liberation movement, Animal Liberation. Undergraduates who study social or environmental ethics are more likely to read a shorter summary of his argument: Singer’s article ‘All Animals are Equal’. The title is an allusion to an oft-quoted line from George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945): “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.” Singer not only challenges the totalitarianism that arises when the pigs (the metaphorical aristocracy on Orwell’s farm) gain absolute power, but the speciesism prevalent in both Western and global cultures.

Like racism and sexism, ‘speciesism’ denotes a specific prejudice and subsequent form of subjugation. Singer intimates that speciesism (a term he attributes to Richard Ryder) involves seeing nonhuman animals as having a lower status than human beings, and systematically preventing their access to certain basic rights humans enjoy. According to Singer, “Experimenting on animals, and eating their flesh, are perhaps the two major forms of speciesism in our society.”

Although Singer’s work was formative for animal rights, it is based in part on the work of Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832). Bentham was a British philosopher and social reformer, and one of the pioneers of utilitarianism. Utilitarianism maintains that to be moral, an action must seek to enable the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

Bentham’s godson John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) later developed his own version of utilitarianism. In Mill’s version, the test of creating the greatest happiness is applied not to individual actions as in Bentham’s ‘Act Utilitarianism’, but instead is applied to types of actions, allowing us to develop rules which if followed will tend to create the greatest happiness. For this reason his version is called ‘Rule Utilitarianism’. However, there is another even more relevant difference between their two approaches. Unlike Aristotle, who believed that happiness was achieved by cultivating the right kind of character and living a balance between the extreme vices of excess and deficiency; and unlike Mill, who distinguished intellectual from sensual pleasures, Bentham maintained that happiness was equivalent to pleasure, and that all pleasures were equal.

To understand how Bentham influenced Singer’s philosophy, we need to understand this idea that there is no distinction between the higher and lower pleasures: between pleasures that most would consider more refined and morally formative – seeing a first rate production of a Shakespeare play, for example – and those which might be labelled inane and base – watching reality television for example. Bentham was ahead of his time in that he also felt that the pleasures of women and animals were no less important than the pleasures of men. In this he was a forerunner of both women’s rights and animal liberation.

At the outset of Animal Liberation, Singer quotes a passage from Bentham’s Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1780):

“The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may one day come to be recognized that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason, or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose they were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?” (p.311)

Similarily, at the core of Singer’s argument against speciesism is the claim that animal rights (and what exactly Singer means by ‘rights’ is debatable) are based not on their levels of intelligence, but rather on their ability to suffer. Animals certainly know pain, and I would add that they know fear as well. Singer argues that “there can be no moral justification for regarding the pain (or pleasure) that animals feel as less important than the same amount of pain (or pleasure) felt by humans” (Animal Liberation, p.15). This aligns with Bentham’s utilitarianism. Furthermore, as Bentham notes, many grown animals are far more intelligent than newborn babies, but we accord newborn babies rights. This then is the basis by which animals should not be seen as mere means to human ends, but, rather, as ‘ends in themselves’ as Immanuel Kant would put it. We might express the same thought by saying that animals have intrinsic worth and autonomy.

Human Speciesism & Vegetarianism

The fourth chapter of Animal Liberation is a justification for vegetarianism. Some people are vegetarians for health reasons, others for moral ones. Singer falls into the latter camp. “It is not practically possible,” he writes, “to rear animals for food on a large scale without inflicting considerable suffering” (p.160). Anyone who has studied factory farming is aware of this (although one also thinks of the work of Dr Temple Grandin, who developed a more humane abattoir for the slaughter of cows, pigs, and sheep).

Human beings are generally speciesist. Singer writes, “Just as most human beings are speciesists in their readiness to cause pain to animals when they would not cause a similar pain to humans for the same reason, so most human beings are speciesists in their readiness to kill other animals when they would not kill human beings” (p.17). Like most oppressors, speciesists assume that their approach to the other – in this case animals – is justified. Such views are precognitive: we hold them because we haven’t thought about them. Most people do not consciously consider the status they lord over nonhuman animals. Part of the goal of any liberation movement is to cause the oppressors to lucidly see their own prejudices. Change can only be achieved through a clarified vision. It is Singer’s goal to get people to see their prejudiced thinking about nonhuman animals.

There are numerous critiques of Singer – a prominent one being rooted in the law of the jungle. Animals eat other animals, the critics say; they kill each another with unparalleled savagery. Moreover, we are naturally carnivores. The primary function of our cuspids (a.k.a. our canine teeth) is to tear flesh. Even if it was not our original form, we’ve evolved to be meat eaters.

The moral philosopher R.M. Hare (1919-2002) claimed that there is a difference between causing animals suffering and killing them for food, especially given that in the wild, animals typically have rough lives. In his essay ‘Why I Am Only a Demi-Vegetarian’ (1993), Hare wrote,

“We have to ask… whether the entire process of raising animals and then killing them to eat causes them more harm overall than benefit. My answer is that, assuming, as we must assume if we are to keep the ‘killing’ argument distinct from the ‘suffering’ argument, that they are happy while they live, it does not. For it is better for an animal to have a happy life, even if it is a short one, than no life at all.”

Although logically defendable, there is something unsettling about Hare’s argument. He writes as if there are only two alternatives for animals: life in the harsh wild, or a comfortable yet short existence on a farm. Clearly there are other options. Furthermore, as both Singer and Grandin have shown, life on a factory farm is not a comfortable alternative to life in the wild. Moreover, if we could create a utopia for humans that would require our lives to be cut short (as in the film Logan’s Run), would we feel that such a world was better than our current existence, even given all the difficulties and hardships we incur?

Adding to Singer’s Arguments

Clearly there are particular rights that we cannot bequeath to nonhuman animals. Animals cannot vote or drive a vehicle, for example; yet neither can newborn babies. But although animals lack the intellectual ability to perform certain tasks, this doesn’t mean they don’t deserve basic rights which take their ability to experience pain and fear into account. The two issues are unrelated. And what about the fact that animals are superior to us in other respects? Acinonyx jubatus, commonly known as the cheetah, can accelerate from zero to sixty in three seconds and can reach up to seventy-five miles per hour. Those humans who can run a five minute mile travel at twelve miles per hour. Does that make us inferior to cheetahs? It certainly does in terms of speed, but certainly not in terms of moral worth. Similar comparisons can be made with golden eagles, who can carry four times their body weight in flight; or silverback gorillas, who can lift two thousand kilos (or 4,400 pounds – the equivalent of twenty-five adults) over their heads. Our strength does not compare. Surely this does not make us morally inferior beings – a species deserving fewer rights? But one could argue that basing moral rights on intelligence is as arbitrary as using strength as the rule. However, if intelligence is to be the rule, surely there could be a species far more intelligent than Homo sapiens. Would that change our thinking here?

I concur with Singer that nonhuman animals have a right not to suffer, due not to their cognitive ability but to the fact that they can experience pain (I also add fear to the equation). But surely the intellectual ability of nonhuman animals is a factor in how they are morally perceived by the majority of people. If nonhuman animals had intellectual abilities akin to humans, that would certainly influence our thinking regarding the numerous ways we use them: for food, clothing, sport, entertainment, protection, and so forth. Intellectual ability is already a common consideration, in fact. Some people protest the use of mice in medical experiments, but not as much as they do the use of monkeys and other primates. Size is also a factor. If I catch a small fish and eat him for dinner, not too many people would be outraged, although many more would if I did the same with a large shark.

It’s arduous, if not impossible, to discern the IQ of nonhuman animals. That said, scientists and zoologists have shown that chimpanzees are quite similar to us in terms of physical traits, reasoning, even DNA. And dolphins are creative. According to an online article by NBC News, a “dolphin in Australia uses a sponge to protect her snout when foraging on the seafloor, a tool use behavior that is passed on from mother to daughter.” Elephants mourn their dead. Squirrels and other rodents practice deception. Crows communicate with one another in a way that only the staunchest skeptic would say is void of reason. Dogs, and pigs, can be highly trained. Clearly, these and other species possess some cognitive abilities. There are also cognitive abilities which nonhuman animals possess that we do not, which suggests a kind of intelligence that we do not have.

For the sake of argument, let’s posit that the average IQ of nonhuman animals is five. (It is probably higher, but I find it hard to believe that it is lower.) The average human IQ is 100. Humans are clearly significantly more intelligent than nonhuman animals. Now let us imagine that a race of extremely clever but callous extraterrestrials with an average IQ of 2,000 visits the Earth. Let’s further imagine that these aliens want to use our flesh for food and our skin and hair for clothing. Maybe the entrepreneurs among them discover that if they double our recommended daily caloric intake and keep us confined in closets, our flesh will become fatter, and more tender due to our lack of movement. They also want to experiment on us for scientific and cosmetic reasons, so they construct special laboratories in which we are experimented on. Maybe they are small enough to ride on our shoulders for sport and transportation, and decide to hold competitions in which they drive us; or maybe they make us race one another on specially build tracks. Who knows what else they may decide to do. Maybe they’ll put two of us in a small ring and watch us brutally claw each another to death. Or maybe they’ll make us run through the wild as they stalk us and shoot at us with laser guns. Would such practices be ethically acceptable? Would these aliens be justified in treating us this way? Remember, they are far more intelligent than us. In fact, their ratio of intelligence to ours is the same as (if not higher than) our ratio of intelligence to that of nonhuman animals.

The question is obviously rhetorical. Of course we would not qualify such exploitation as ethical. In fact, as much as it was in our power, we would rebel against our captors. This is the precise impetus for most liberation movements – the oppressed revolt when they can no longer tolerate their subjugation.

For utilitarianism oppression is unethical regardless of the intelligence level of the oppressed. We noted that Jeremy Bentham’s brand of utilitarianism did not take levels of intelligence or even membership in a specific species into account. Bentham, as you may recall, maintained that the pleasures enjoyed by the beast were no different to those in which the most ‘cultured’ among us indulge. Listening to J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto performed by the Handel and Haydn Society while imbibing a glass of Château Lafite Rothschild would give a tremendous sense of pleasure to the elite erudite sophisticate, whereas someone else would find a similar degree of enjoyment (according to Bentham’s Felicific Calculus) watching The Jerry Springer Show while guzzling a six-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer. According to Bentham, if they yield a similar degree of happiness, they are ethically equal.

Bentham did not distinguish between the higher and lower pleasures, but his counterpart one generation removed did. In an oft-quoted passage from his 1863 book Utilitarianism, Mill writes:

“It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, is of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question. The other party to the comparison knows both sides” (Utilitarianism p.10).

But if pleasure and degrees of happiness are relative instead of comparative, then human pleasures are not superior to animal pleasures. (In fact, the phrase ‘human pleasures’ is a misnomer, since pleasures vary among humans.) Therefore, the pleasures of an extraterrestrial race are not superior to human pleasures, they’d simply be different. This is the basis by which we would critique alien exploitation: “Just because they possess a higher degree of intelligence,” we would say, “this does not afford them the right to infringe upon our rights.” This polemic would be ethically justified.

This article is not an exercise in science fiction, although what I propose sounds an awful lot like the classic 1962 Twilight Zone episode ‘To Serve Man’. If aliens do exist, it is conceivable that one or several species of them would be vastly more intelligent than us. But even if there were none, the point of the comparison still holds: level of intelligence does not determine moral worth. If it did we could justify using people who are severely mentally disabled for medical testing. Nazi doctors did so, on people they were led to consider subhuman. Nazi propaganda films such as The Eternal Jew (1940) compared Jews to rats to promote the Final Solution. Other films produced by the Third Reich justified the extermination of the severely mentally disabled by making similar claims. I am not comparing your average meat eater to a Nazi; nor am I minimizing the plight of the Jews in 1930s Germany by equating it with the evils of factory farming. What I am saying is that the victim of our whims, whoever they may be, must be delegitimized and not just dehumanized in order to justify their exploitation. When it comes to animals, we primarily base such delegitimization on cognitive ability. No moral theory can ever rationalize this. The question before us is why is this used to justify how we treat animals, when we would never use this argument to validate the similar treatment of human beings?

© Prof. John Tamilio III 2021

John Tamilio III is Visiting Associate Professor in Philosophy at Salem State University and is Pastor of the Congregational Church of Canton, Massachusetts.