Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Cynical Theories by James Lindsay & Helen Pluckrose

Stephen Anderson takes Social Justice Warriors to philosophical task.

The spectacle of benighted cities overrun with black-clad marauders, downtowns declared ‘sovereign territory’, businesses sacked, churches aflame, and police squads besieged by angry demonstrators, in the leading democratic countries of the world, gobsmacked the public in 2020. How modern civilization has degenerated to such a point is one of the many marvels of what anyone must admit was a very memorable year.

Into this situation has come a new book authored by James Lindsay and Helen Pluckrose, Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender and Identity – And Why This Harms Everybody (2020). Pluckrose and Lindsay, you might remember, are two of the three scholars implicated in the famous ‘Sokal Squared Hoax’, involving the producing of fake academic papers with subjects such as whether dog parks were part of ‘rape culture’ or the ethnographic analysis of men who attend ‘breastuarants’. Silly enough to be laughable, but couched in postmodern academic jargon, several such papers passed for serious contributions to Social Justice Studies and were subsequently published in peer-reviewed journals. The tectonics, and high hilarity, produced by the scandal, have continued to reverberate throughout academia since. In this book, however, Lindsay and Pluckrose take on a more serious task: that of illuminating how academia ever fell to such a low-level of critical self-awareness, and how the public has followed it into postmodern follies of various kinds.

Being critical of theories

Philosophers’ curiosity runs well beyond the mere news details, or even the surface sociology, to the root thinking powering such developments. The actions of ordinary people are usually downstream from some important ideological shift, and such is the case here. The argument of Cynical Theories is that the ideology that gives common cause to movements such as Black Lives Matter and Antifa, and which has also powered the riots in major cities in the developed world, originates from a form of neo-Marxist thinking produced by the Frankfurt School, Antonio Gramsci and the postmodern critical analysis of Michel Foucault. If so, then understanding its roots and its objectives is very much in the interest of anyone interested in understanding today’s headlines.

The key culprit is called ‘Critical Theory’, which is the philosophical framework developed by the Frankfurt School, and which underwrites such various subjects as Women’s Studies, Queer Studies, Gender Studies, Postcolonial Studies, Fat Studies, Disability Studies, and Critical Race Theory. In their practical applications, these disciplines have fed into the various street-level movements we now know under the umbrella of ‘Social Justice’, some of which movements have recently set our cities on fire. The authors of Cynical Theories pull apart the guts of Critical Theory, showing its derivation, its history, and its consequences going forward.

The story generally goes like this: From the 1960s to the 90s, postmodernism began to take hold in universities and schools in the West. Generally a skeptical, critical frame of mind, postmodernism tended to follow the psychologist Jacques Lacan’s famous dictum of ‘incredulity toward metanarratives’. This meant: be suspicious of all big stories about history, morality, or truth – such as the myth of progress, traditional Judeo-Christian morality, ideas of ultimate truth, or accounts of history that valorize the West. But as the Twenty-First Century dawned, this purely negative kind of analysis lacked practical application, or the potential for underpinning political action.

Clearly, that changed. But how? According to Lindsay and Pluckrose, the key development was that ordinary people, not just academics, began to take to heart the assumptions of postmodern academics such as Jacques Derrida and Foucault, including such beliefs as: “all white people are racist, all men are sexist, racism and sexism are systems… sex is not biological, language can be literal violence, denial of gender identity is killing people, the wish to remedy disability and obesity is hateful, and everything needs to be decolonized” (p.183). Such beliefs, they say, congealed into a sort of Gospel of Social Justice – a ‘good news’ reified into a set of popular absolute ‘known knowns’ which cannot ever be doubted or examined without the critic instantly indicting himself as an ‘oppressor’.

Moreover, the traditional liberal critical resources of logic, reason, evidence, and science, are absolutely eschewed by today’s social critics, under the supposition that such values are themselves infected or ‘colonized’ by ideas such as patriarchy and white supremacy. In their place, the lived experiences of ‘victims’ and ‘oppressed social groups’ are elevated to the status of data, giving SJWs the right to shout down all the conventional methods of sorting out universal truth from mere partisanship. Activists have thus become addicted to dysfunctional shows of social justice virtue, including street violence, while real issues of poverty, human rights, identity, morality, truth and actual injustice often go begging. Worst of all, the traditional liberal values of freedom, choice, individuality, opportunity, and so on, are thoroughly undermined by this impulsive, contentious, group-think-based way of seeing the world.

In the end, traditional liberal values are what Lindsay and Pluckrose are plumping for. They advocate a return to centrist scholarship and classical liberalism. They conclude with a set of proposals for rethinking concepts such as ‘justice’ and ‘equity’, along lines allegedly more harmonious with reason, proof, logic, evidence, individuality, and choice, and less encumbered by group-think and by obscurantist, inflammatory collectivist rhetoric. Less propaganda, more humanity, is their ultimate objective.

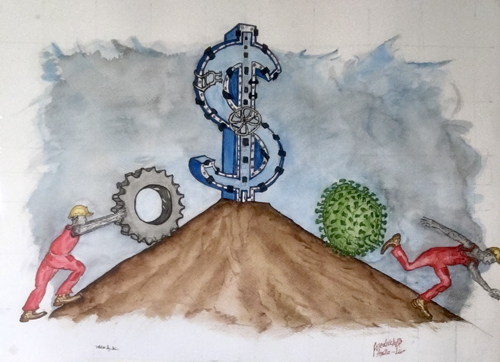

International Workers’ Day Impacted by Corona by Farshaad Razmjouie

However, it’s here that the one major weakness of their thesis also appears. For Lindsay and Pluckrose seem to imply that secular rationalism, the scientific method, and the idea of human rights, leapt into existence ex nihilo in the Eighteenth Century, as a pure gift of the Enlightenment, without social conditions or progenitors. They don’t seem to have wondered why these values appeared where they did and when they did, rather than at other times and places in history. For instance, they don’t question where Sir Francis Bacon derived his ideas for the scientific method, or John Locke his conceptions of human rights, even though both are keystones of the liberal scientific rationalism they espouse. So while it is quite fair for Lindsay and Pluckrose to criticise postmodernism for arbitrarily exempting its own metanarrative from being critically deconstructed, the very same charge of ‘historical denial’ could be leveled against them in return. This is unfortunate. If, as they insist, modernism itself gave rise to the conditions that produced postmodernism and Critical Theory, then it’s hard to see how reversion to those same modernist values would be likely to fix anything. In fact, classical secular liberalism has its own historical and ideological history, and understanding the particulars could well be key to understanding what really went wrong in its application. Something more is needed there.

As you might suspect with any two-author book, there’s a bit of unevenness between the two styles of writing: one is caustic and clear, though not unfairly terse; the other is more cautious, more deferential to the various social justice disciplines, and somewhat more cluttered. But the contrast in style is not offensive, and in the end turns out to be an advantage. Whenever the description becomes too detailed, the writing soon breaks out into the open space of thought and gives the reader air.

This isn’t a hard book to read, and it’s certainly suitable for the Philosophy Now audience, but it is thoroughly documented, so is not quite a popular-level offering. It hovers between the academic and popular levels, really. Overall, though, this is a book that should be read by anyone with a serious interest in the origins of today’s events in regard to the ideology of Social Justice. Every politician should have a copy. And it would do a lot of good in the Humanities courses of the (post)modern university if this book were required reading along with the various social justice texts they already make mandatory – not just to provide ideological balance, but because it contains a thorough and fair history of the whole movement, from a helicopter-view perspective.

© Dr. Stephen L. Anderson 2021

Stephen Anderson is a retired philosophy teacher in London, Ontario.

• Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender and Identity – And Why This Harms Everybody, by James Lindsay and Helen Pluckrose, Pitchstone Publishing, 2020, 352pp, $20 hb, ISBN: 978-1634312028