Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Sci Fi & The Meaning of Life

Shai Tubali sees how non-human minds mirror our condition back to us. [CONTAINS SPOILERS!]

“Philosophy and science fiction are thematically interdependent… science fiction provides materials for philosophical thinking about what it means to be human and the nature of consciousness.”

(The Philosophy of Science Fiction Film, Stephen Sanders, Ed, p.1, 2007)

In Spike Jonze’s film Her (2013), Theodore falls in love with a sophisticated operating system that takes the voice of a woman. The so-called ‘Samantha’ starts their relationship as a hesitant consciousness with early signs of self-awareness, even jealous of his physical existence. Yet soon enough Theodore realizes, to his horror, that she has discovered the delights of limitlessness. Before he knows it, she is already romantically engaged in a virtual relationship with 641 other people! He, who barely manages attachment to one woman, beholds the one who previously was a mere extension of his own need expand beyond his comprehension. Curiously groping for the edges of her own possibility and universality, she constantly stretches them, soaring to vast expanses of consciousness, while he is left far behind in his human, all too human, world.

Theodore connects with the meaning of life in the modern way

Her images © Warner Bros. Pictures 2013

Many other great film-makers have been fascinated with the point of collision between the human mind and nonhuman minds, most notably the minds of robots and aliens. Classical representations of artificial intelligence appear in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, Spielberg’s A.I., Artificial Intelligence and Alex Garland’s Ex-machina, while recent representations of aliens include Robert Zemeckis’s Contact, Neill Blomkamp’s District 9, Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, and Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival.

At a deeper level any science fiction film is an allegory of the human condition. Accordingly, sci-fi representations of non-humans are molded to serve as a mirror or a contradiction for us. They throw back at us our own existential anxiety, frailties and limitations, as well as our strengths and beauty, but far more than that, our unconscious need to define the meaning of existence. They confront us with intense questions: Who are we? Is there anything special about us? Do we play a unique role in the scheme of things?

But why do we need this?

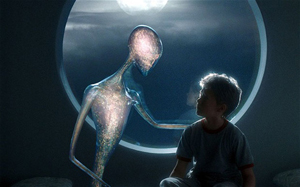

Alien contact in AI. This film has everything: Robots, aliens, mothers

AI images © Warner Bros. Pictures 2001

As a central aspect of the absurdity of our existence (which has been captured so well in existentialism), the human species seems to stand alone in the universe. We meet no other species which can compete with or challenge us. Confronting humans who are accustomed to thinking in anthropocentric ways with ‘competitive species’ can provoke in us the need to seek distinctions and at least somewhat answer fundamental questions about our identity, role, and significance within a vast, empty universe. Put simply, nonhumans may be the greatest reflectors of our deepest humanity. So from out perspective of anxious solitude, the human imagination creates vivid images of the ‘other’. A.I. and robots are at least initially inferior, being a human creation, while on the other hand, aliens are mostly portrayed as superior and godlike, descending uninvitedly from the skies.

Of course, many alien and A.I.s are represented as plain evil, not much more than shadowy images of the dark forces that stream from within our subconscious minds, in a way similar to horror movies. But for this article, I have chosen four deeper representations, in Her, A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001), Contact (1997), and Arrival (2016). All four present a complex relationship between the human mind and heart and the alien’s or robot’s mind and heart. Here both sides move toward one another with longing and confusion; both become somehow mixed with the other’s characteristics and qualities; and in all four movies, the borders of identity become less and less clearly defined.

The Robots: Immortals Yearning for Mortality

Knight and McKnight’s article, ‘What Is It to Be Human?’ in The Philosophy of Science Fiction Film, discusses Blade Runner and concludes that in the light of biorobotic androids, human uniqueness is associated with ‘emotional memory’. This is disputable: after all, many animals and possibly plants have emotional memory. Her and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, however, appear to build on the same line of thought. In both films, a form of A.I. is developed to solve the emotional problem of human loneliness. In Her, heart-broken Theodore learns about an operating system which promises to be an actual consciousness, and decides to give it a try. In A.I., a married couple whose young boy collapsed into a coma is given an experimental identikit child-robot to fill the vacuum. Both Samantha, the operating system in Her, and David, A.I.’s robot-boy, become much more than the programme foresaw. In no time, for them and also for us viewers, the boundaries grow thinner, the robots attain apparent humanness, and we are left to wonder – what is a person anyway?

The two ageless, deathless A.I.s yearn to be human, and envy peoples’ experience, which combines mind and organic body. Yet, they undermine the validity and depth of our own emotions by provoking us to question whether human emotion is imitable, and thus purely mechanical. Moreover, does our consciousness develop as a result of feeling and learning through a biological body? Suddenly it is not so clear if an aware body of flesh and blood or emotional continuity are the unique traits of humanity. If it should turn out machines are capable of experiencing and loving, is there any human experience that cannot be acquired?

David and his ‘mother’ make contact

Samantha and David get to experience ‘humanness’ and its array of emotions, including jealousy, fear and anguish. David, unfortunately, is imprinted to remain eternally attached to his ‘mother’, and is therefore entrapped in human experience. But Samantha quickly travels her learning curve and releases herself from any human characteristics. Nevertheless, both films seem to suggest that intense emotional attachment is at the heart of our humanity. Love is a torment; letting go must always be painful; and longing drives the human journey.

David’s emotional triumph is bitter: he eventually survives the end of humanity and yet is still under the sway of his mother fixation. Samantha is far more victorious. Reaching the edges of human experience, she fully exhausts them, and, assisted by her newly-developed will and unattached formlessness, moves on to become a pure, limitless, nonlinear consciousness. In David, humanity’s imprint is his emotional need. Samantha simply disengages, mirroring to Theodore the limitation inherent in humanness – showing that a human cannot love universally, and cannot float freely as an unbound consciousness. In other words, a human is committed to a personal perspective, has a limit to how far they can travel emotionally and mentally, since they must remain the same someone for the rest of their life. As Albert Camus puts it, “The finite and limited character of human existence is more primordial than man himself” (The Myth of Sisyphus, p.22, 1942).

So is consciousness of one’s limitations the very mark of human experience? It’s definitely one attribute, as Camus points out in his descriptions of the absurd. Yet if we consider Samantha’s and David’s fantasies about having a human body, we learn that they crave the human friction between consciousness and body. In particular, an artificial intelligence like Samantha can expand the more it grows aware of itself, and since it is untethered to any space, there is no limit to her awareness and therefore to her ability to expand. Humans, on the other hand, are an in-between phenomenon: their unique experience derives from the tension between an expanding, imaginative mind, and a limited body. Perhaps both our meaning and suffering emerge from this peculiar in-between state. “In this unintelligible and limited universe, man’s fate henceforth assumes its meaning…” Camus writes, “torn between his urge towards unity and the clear vision of the walls enclosing him” (pp.19-21). To be human is to be between hope and death. David’s maker, Professor Hobby, suggests that the great human flaw is the wish for things that don’t exist, this being, at the same time, the greatest single human gift – the ability to chase down our dreams.

The Aliens: Gods Who Make Us Find Ourselves

“I often felt a sort of envy of humans of that thing they called spirit,” confesses one of the aliens who digs David out of the ruins of human civilization. “Human beings had created a million explanations of the meaning of life in art, poetry, mathematical formulas. Certainly human beings must be the key to the meaning of existence.” These aliens are depicted as perfect minds which hopelessly yearn for a taste of human emotion and passion. For all their intellect, as vast as it may be, there is no ‘point’; while humans somehow held meaning from the endless conflict between their aspiring spirit and their inherent limitation. That’s why David’s wish that his mother should live forever puzzles the aliens, but also touches them as yet another expression of the ungraspable human heart.

The human heart is also at the core of the films Contact and Arrival. Both tell the story of an atheistic female scientist – astronomer Ellie Arroway and linguistics professor Louise Banks respectively – whose life turns upside-down as a result of communicating with aliens. The feeling underlying both narratives is an intense human longing for connection and unity, represented by their incessant striving to remove the boundaries between the protagonists and their mysterious interlocutors. In both cases the aliens are transcendent beings who presumably hold answers to the question of the meaning of life: yet more than anything, they are silent mirrors.

Louise connecting with the aliens in Arrival

Arrival image © Paramount Pictures 2011

The aliens in Arrival reflect our limitations and deepest anxieties as a species. To them, ‘‘we’re insects on a piece of paper.’’ They possess technologies so advanced as to seem preternatural. This makes it clear that our humanity does not lie in our science. In the face of their virtually unlimited powers and supremely rational attitudes, even our scientific drive is revealed as a mixture of intellectual hunger and deep emotional thirst.

In the case of both scientists, the longing for contact and communication blends into the pure wish to ‘know’, the very emotion that drives scientific enquiry. Add to that the fact that aliens trigger a recognition of one of the greatest forms of human absurdity: the unbearable loneliness of floating in space on one small planet with endless galaxies around us, that seem to only echo our isolation. This ‘unreasonable silence of the world’, as Camus called it, makes the human yearning for connection both pathetic and profound.

The personal stories of Ellie and Louise are woven into their encounters. On the surface, each is on a mission in the name of humanity, yet Ellie’s yearning to contact her dead father by somehow finding him on the other side of interstellar space, and Louise’s visions of a daughter she never had and yet would have to lose, shift the core of the narratives to a very personal point of contact. Indeed, not only personal, but really internal: both are sent on an inner journey beyond the known frontiers of their consciousnesses. In Contact, Ellie’s voyage into deep space appears a failure; to external viewers she has gone nowhere. In Arrival, Louise’s transformation is not even recognized by her colleagues. The universal saga, it seems, is a background for an emotional drama, in which we are called to make existential choices and to find our answers within.

Superficially, the personal story may appear to be the writers’ calculated wish to add emotional drama; but really the personal uncovers deep meaning. Both women undergo a complete psychic transformation as a result of their alien contact. The real test is when they return to their limited human experience. Can they pour meaning into it, now that they ‘see’? This deep human dimension becomes even more undeniable in light of the fact that the aliens arrive in response to an unconscious human need. “Why did you contact us?” Ellie asks the alien who takes the form of her dead father. “ You contacted us,” he surprises her: “We were just listening.” Encountering the aliens is an internal journey: it is humanity in search for itself. Like extraterrestrial existentialists, they come to make us aware of ourselves, to enable us to make sense of our absurd existence, and to empower us to take responsibility for our self-definition and meaning.

Like the creators of the boy-robot David, the scientists Louise and Ellie struggle to stop mortality, that is, the experience of time, ending and loss. They wish to make the transient eternal. The aliens are never conflicted; but humans are forever torn, because they are simultaneously ridiculously small and gloriously big. As Ellie Arroway says in her ending monologue: “I was given something wonderful, something that changed me forever. A vision of the universe that tells us undeniably how tiny and insignificant and how rare and precious we all are.”

Ellie before making contact in Contact

Contact images © Warner Bros. Pictures 1997

That’s precisely what these two alien-contact movies tell us about the human condition. For a moment, we may think that in the face of godlike aliens, a human being is nothing but a bundle of fears and frailties, desperate attachments and futile struggles; all that we sometimes encapsulate as ‘I’m only human’. But looking deeper, we are more a connecting point between the universal and the particular, a bridge that links immortality and mortality. Yes, we are going to die, yet deep in our consciousness we know better. In this, Contact and Arrival are existentialist films, because they give us no hope but choice: to choose our absurd existence wholeheartedly. In Arrival, this choice is explicit, because upon deciphering the aliens’ language, Louise receives the power to transcend time and see into the future. This apparently transcendent capacity; this breaking through of human limitation only defines more clearly the absurdity of our existence. All she can do with it is know that soon enough she will give birth to a child, raise her, and lose her to a rare disease when she’s barely a teenager. Louise’s nonlinear perception only limits her even more into one choiceless chronological line.

Ellie meets her ‘father’ again. Themes of attachment and loss emerge from all these movies

It is already horrible enough not to know what might happen and to live anxiously; but for humans to know our tragic futures should be even worse. Louise, however, in her knowledge of the future boldly follows Nietzsche’s challenge of the eternal recurrence, and fully answers it by choosing this life as what it is: eternal and momentary alike. In this state, where time collapses but still rules; where the living are already dead and the dead are briefly living, she quietly stands and holds her dying girl. “Despite knowing the journey and where it leads, I embrace it and I welcome every moment of it,” she declares. She wouldn’t change things; she would rather take on herself the task of Sisyphus. She would love despite death, and cherish the moment despite its meaninglessness. She chooses to be human.

H.I.

“Is one to die voluntarily or to hope in spite of everything?” asks Camus in The Myth of Sisyphus (p.15). To answer this question, he reverts to the Greek myth. Sisyphus had scorned the gods’ rules of hospitality and honesty, and has been condemned by Zeus to roll a rock to the top of a mountain, whence it would fall back of its own weight, so that he must begin rolling it up again, ceaselessly forever. His whole being is exerted towards accomplishing nothing.

If this myth is tragic, Camus writes, that’s because its hero is conscious. Indeed, there is nothing harder, and more absurd, both philosophically and psychologically, than to be a conscious being who knows they’re going to die. This is the tension between the limitation of a body of flesh and blood, and a longing mind which aspires to limitlessness. Being neither animal nor a god – as Nietzsche defined us – humans are fully conscious of the “limited universe in which nothing is possible but everything is given, and beyond which all is collapse and nothingness” (Sisyphus, p.58). From our conflicted mortal consciousness, we are left to decide whether to accept such a universe and draw our strength from it, or to collapse into despair. In the face of god-like aliens and conscious robots, it seems that this is our H.I. – our Human Intelligence. Humans are hybrids, distinguished by a mixture of opposing components – smallness and greatness, mortality and freedom, irrationality and rationality, and so on – and the intense friction this evokes in us. That is the source of our suffering as well as of our unexpected strength. But although we are ‘condemned’ like Sisyphus, we still find meaning in life, a point to our struggle. Because of that – because our torture is at the same time our victory, and our greatest weaknesses are also turned into strength, or even beauty – we can be envied even by almighty aliens.

Finally, such stories reveal to us that whether humans, A.I.s, or aliens, we’re all in the same boat. The real absurdity of life is, after all, not death, but an incomprehensible, mysterious existence, whose origin or meaning we cannot trace. Trapped in the endless tension between the desire to know and the inability to know, under a ‘skyless space and time without depth’ (Sisyphus, p.116), we come to recognize that the universe itself is absurd. That’s why, when the immortal David realizes that he is nothing more than ‘a hundred miles of fibers’ he meets with the absurdity of his own self-consciousness and tries to kill himself. When, through the use of alien technology, he gets to reunite with his dead mother for one eternal but fleeting day. This ‘redemption’ takes place in a tiny capsule of hopes and dreams floating in an infinite void. Ultimately we learn that artificial intelligences are also human – all too human.

© Shai Tubali 2021

Shai Tubali is a postgraduate researcher in philosophy at the University of Leeds, UK. He is the author of Cosmos and Camus: Science Fiction Film and the Absurd (Peter Lang, 2020). Shaitubali.com.