Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Good Sport by Thomas H. Murray

Dan Ray asks why drugs cannot be a part of good sport.

In a 2001 Nike ad that aired a dozen years before he admitted to using performance-enhancing drugs, the cyclist Lance Armstrong calmly sits inside the eye of a media storm. TV cameras, shouting reporters, and flashbulb lights tightly encircle him, while a doctor cautiously removes a vial of blood from his strong, lean arm. “Everybody wants to know what I’m on,” Armstrong says, before pompously declaring, “What am I on? I’m on my bike six hours a day busting my arse. What are you on?”

Anyone watching that commercial on YouTube today, almost a decade after an Armstrong-centred doping scandal nearly destroyed professional cycling, likely feels a tinge of disgust or even anger at his words. Indeed, the name ‘Lance Armstrong’ has grown synonymous with cheating and hypocrisy in sport. The dominant view today, even among people who don’t care a wit about cycling, seems to be that his accomplishments – including seven Tour de France titles – were unearned, or at least unfairly gained.

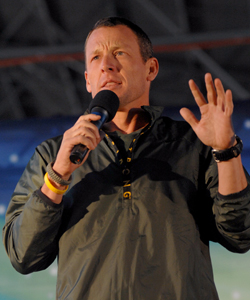

Lance Armstrong on a bike, on a hill, on amphetimines?

Armstrong © Filip Bossuyt 2009

But are such views justified? What’s wrong, after all, with an athlete applying performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) to his or her own body to reach otherwise unattainable heights? Aren’t PEDs just an extension of the advanced technologies and training techniques that top-flight athletes already employ? These are a few of the questions that Thomas H. Murray considers in his lively and illuminating book Good Sport: Why Our Games Matter – and How Doping Undermines Them.

Murray, an ethicist who has served as chair of the Ethical Issues Review Panel for the World Anti-Doping Agency, is well acquainted with the ethical grey areas involved in cases like Armstrong’s. He has heard all the arguments that coaches, athletes, doctors, and other pundits have concocted to defend the use of PEDs in sport or to accentuate the futility of regulating them. In Good Sport, he peels back the oft-tempting veneer of these arguments while repeatedly underscoring a few central ideals that all sport aficionados embrace, even if only subconsciously. Specifically, Murray tells us that sport showcases “excellent performance as the product of natural talents”; “the dedication required to perfect those talents”; and “the courage to perform under pressure” (p.149). Innate ability, hard work, and guts: this constitutes the triad of human properties on display in any sport, according to Murray, and audiences want to see competitions in which some combination of them is decisive.

Murray points out that referees, governing bodies, and even fans of sport, work to eliminate all other factors that might creep into that formula by drafting myriad rules and bylaws. The peculiar distance between the pitcher’s rubber and home plate in baseball – 60 feet 6 inches – is just one example Murray uses to illustrate the idea that rules in sport “create a tension, a real contest” between competitors (p.51). Move the pitcher just a few steps closer to the plate, and the batter will miss every time; move him a few steps farther back, and almost every pitch will be knocked into a gap. Baseball fans don’t want the pitcher to win just because he’s the pitcher. They want the pitcher’s skills closely balanced against the batter’s so that the skills themselves decide the outcome. Such rules, which abound in sport, from weight categories in boxing to gender designations in the 800-meter run, may seem arbitrary, but, on closer examination, reflect sport’s core values.

Murray observes that rules surrounding the use of technologies, including the use of performance-enhancing drugs, are of the same character: messy, and, at first blush, completely arbitrary. Why do modern pole-vaulters, for example, get to use fiberglass poles over the bamboo or cedar ones they once used? Fiberglass poles allow vaulters to clear heights that would have been unimaginable with the previous materials. How are such radical changes permitted or even embraced by fans and governing bodies, while others are ridiculed and outlawed?

Lance Armstrong holds his hands up

Armstrong © Tabitha M. Mans 2007

As Murray explains, “Rules in sport have an essential function: to select from among the myriad differences among players the ones that should affect outcomes” (p.51). So sports are designed to cancel out the variables that spectators and participants don’t think should decide the result. Doing so isolates talent, dedication, and guts, and puts them on display. Pole vaulters today would obliterate the pole vaulters of the 1960s based on the technology alone. Yet this same technology produces a modern competition with a highly visible differentiation between those who are excellent versus those who are merely very good and arguably this improves the sport. However, performance-enhancing drugs, Murray says, elevate other values, such as access to high-priced medications or a willingness to experiment with drug cocktails, into the realm of the decisive, and so are not good sport (p.141).

Murray reminds us that some commentators have characterized Lance Armstrong’s doping as “a vision of sports in which the object of competition is to use science, intelligence, and sheer will to conquer natural difference” (p.10). This view echoes Armstrong’s own words in his 2001 ad: “This is my body. And I can do whatever I want to it. I can push it, study it, tweak it.” But fans turned on Armstrong because his pharmacological tweaks were so potent that they mattered more than his talent or how many hours he laboured on his bike.

Some drugs are decisive, others are not, and still others have less certain effects. The magnitude of the effect is what matters. Using this fragile litmus test to permit or ban a drug is not clean or simple – grey areas abound. But Murray encourages us to work in these grey areas: “This is not the kind of problem that can be solved once and for all; rather, it’s an enduring tension we must continue to monitor attentively” (p.144). To see human gifts, human commitment, and human heroics staged at the highest levels, we have no choice but to contend with doping.

© Dan Ray 2021

Dan Ray is a science writer, philosophy reader, and PED-free hobby jogger based in Burlington, Vermont.

• Good Sport: Why Our Games Matter – and How Doping Undermines Them, Thomas H. Murray, 2018, $29.95 hb, Oxford University Press, 195 pages, ISBD: 9780190687984