Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Huygens: A Scientist Among the Philosophers

Hugh Aldersey-Williams traces the philosophical connections of a polymath.

When the Dutch astronomer and physicist Christiaan Huygens died in 1695 at the age of sixty-six, the German philosopher Gottfried von Leibniz called his loss ‘inestimable’, and hailed him as the equal of Galileo and Descartes. “Helped by what they have done,” Leibniz wrote, “he has surpassed their discoveries. He is one of the prime ornaments of the age.” Indeed, Huygens discovered the rings around Saturn and detected the first moon of that planet. He also created the first accurate pendulum clock, among many other inventions. He described centrifugal force, was the first to employ mathematical formulae in the solution of problems in physics, and devised a foresighted wave-based theory of light. It is largely thanks to his contemporary Isaac Newton that we have mostly overlooked his achievements today. Newton habitually failed to acknowledge the contribution others had made to his discoveries, and Huygens was among those to suffer this fate. This, together with the cult of Newton’s ‘genius’ that grew up during the eighteenth century, ensured that the Englishman’s flawed ‘corpuscular’ theory of light prevailed over Huygens’ version, to the detriment of progress in optics for the next century, since, in contrast to Newtons’ theory, Huygens’ wave theory was substantially correct.

Also unlike Newton, who never travelled much beyond London and Cambridge, Huygens was a well-connected internationalist in science. He was hired by Louis XIV’s powerful minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to direct the newly-founded French Academy of Sciences, as well as becoming the first foreign Fellow of the Royal Society (of science) in Britain. He maintained collaborations and correspondence with astronomers, mathematicians, and scholars throughout Europe. His location in The Hague, at the heart of the prosperous and tolerant Dutch Republic, undoubtedly helped, with a constant traffic of thinkers passing through or seeking refuge there from religious or political persecution in other countries.

Huygens’ intellectual exchanges also incorporated a number of the most important philosophers of the age. His interactions with philosophers were of several kinds. First, there were those who were interested in scientific questions, who provided inspiration and on occasion, cooperation or collaboration. A subset of these could be categorized as ‘science wannabes’ – philosophers who wished to master mathematical methods, envying their rigour, or who felt a need to understand the scientific basics of natural phenomena, if only to avoid error in setting out their own ideas. Then there were yet others with whom Huygens felt himself to be in intellectual harmony.

Huygens by Caspar Netscher, Museum Boerhaave (1671)

Descartes

Undoubtedly the philosopher who had the greatest impact on Huygens’ life and work was René Descartes, who had fled from France to the Dutch Republic in 1629, the year of Huygens’ birth. Descartes soon became friends with Christiaan Huygens’ father, Constantijn, a poet and diplomat with the ruling House of Orange. They worked together in an (unsuccessful) attempt to design a more perfect astronomical lens, and Constantijn was able to use his powerful connections to ensure that Descartes’ Discourse on Method (1637) was published both in Holland and France.

Through the influence of his father and his tutors in mathematics, Christiaan soon became a convinced Cartesian. As a boy, he read Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy when it appeared in 1644. In this book Descartes set out his scientific theories. Huygens responded to its logic and clarity, as well as to the boldness of Descartes’ ambition to construct a new and universal understanding of nature. Although as an adult he may never have met Descartes in person in Holland, Huygens became a sufficient admirer of the Frenchman that in 1649, after completing his college studies, he set off on a journey to seek him out at the Swedish court in Stockholm, where he was occasionally teaching philosophy to the Queen. However, the trip was cut short, and the following year it was learned that Descartes had died.

As Huygens’ scientific career progressed, however, his growing body of work led him to realize that Descartes – never much of a practical investigator – was not always sound when it came to the observable facts. Huygens always remained guided by the philosopher’s general principles, but he learned to set his ideas aside when they did not accord with his own direct observations or experimental results. Towards the end of his life, Huygens was asked for his comments on the first published biography of Descartes. He wrote:

“Mr. Descartes had found a way of taking conjectures and fictions for truths. Those who read his Principles of Philosophy were struck in the same way as those who read pleasing novels that give the impression of being true stories. It seemed to me when I read this book for the first time that everything was going better in the world, and I thought, when I found some difficulty, that it was my fault that I did not understand his thoughts properly. I was only 15 or 16 years old. Since then, having from time to time discovered things that are obviously false, and others very unlikely, I have quite overcome the fixation I once had, and now I find almost nothing I can approve as true in all the physics or the metaphysics.”

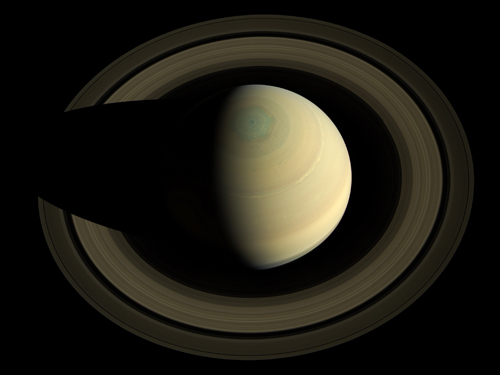

Saturn photographed by the Cassini-Huygens space mission (2004)

© Nasa/Cassini

Spinoza & Leibniz

Huygens enjoyed a more practical association with Baruch Spinoza who, following banishment from his Sephardic Jewish community in Amsterdam for teaching heresies, pursued a quiet trade as a lens-grinder. Spinoza lived in various places, including just outside The Hague, close to where the Huygens family had a villa whose garden Christiaan used for his astronomical observations. Although Huygens typically ground his own lenses for his telescopes, he recognized the excellence of Spinoza’s work and also bought lenses from him. Spinoza was in a sense a competitor, but he was also an occasional collaborator, and he and Huygens sometimes swapped technical information and books. In the spring of 1665, Huygens was able to show Spinoza through his telescope the shadow cast by Saturn’s ring onto that planet’s surface. An unlikely companionship was thus struck up between an excluded Jewish tradesman and a patrician connected at the highest levels of Dutch society, through their shared scientific and technical interests.

Huygens often worked with one of his brothers grinding the lenses for his instruments. Letters written at times when they were apart refer fondly to these periods spent together, which were perhaps some of the happiest in Christiaan’s life. Although lens-grinding demands the greatest concentration over long periods of time, with the slightest slip being enough to ruin a piece of glass, there is a meditative aspect to the work that clearly suited both the Huygens brothers in their companionship, as well as Spinoza in his contemplative solitude. While the Huygenses explored means of automating parts of the process, Spinoza is known to have favoured an entirely manual procedure, by which he remained able to make the minutest adjustments by touch.

Perhaps Spinoza found this patient labour conducive to the thought processes necessary for the creation of humane philosophical works such as his Ethics (1677). Certainly, it is clear from Spinoza’s own writing that there was effectively no separation in his mind between this practical work and the development of his philosophy. For his part, Huygens may well have been influenced by Spinoza’s view of God-as-Nature, hints of which appear in some of Huygens’ later writings, including a book-length speculation about life on other planets.

The other major philosopher with whom Huygens had close personal dealings was Leibniz, who arrived in Paris in 1670 as an envoy of the Elector of Mainz on a peace mission, aged twenty-six, but stayed on to study mathematics with Huygens. Leibniz soon surpassed his tutor, of course, becoming famous as the co-inventor (with Newton) of calculus, among other accomplishments in diverse topics in mathematics, although he was less successful in his efforts as an experimental scientist and inventor. But the two men remained friends, and Leibniz often turned to Huygens for approval, especially concerning his work in geometry, of which Huygens was a master. They also compared notes about such heavyweight topics as Spinoza’s conception of God, which Leibniz found unsatisfactory, and Newton’s ideas about the elliptical orbits of the planets. Here the apparent absence of a natural cause of the gravitational attraction between heavenly bodies troubled both men.

Hobbes

More occasionally, Huygens became entangled with figures who only fancied themselves as mathematicians or scientists. The worst case was the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes was rare among his peers for regarding mathematics as an essential component of philosophical thinking, and he had long admired Huygens’ youthful work in the field. Unfortunately, though, Hobbes’ enthusiasm outran his facility. Huygens was among a number of mathematicians who found themselves obliged to point out the errors in Hobbes’ attempts at geometric proofs of problems such as the squaring of the circle. Huygens found ‘‘nothing solid, only pure visions’’ in one attempt at a geometrical proof by Hobbes; “by dint of being absurd, it becomes funny,” he wrote to a Scottish colleague. But Huygens worried that by troubling to refute Hobbes’ mathematics he might merely be drawing attention to the man’s misguided efforts.

Another of Hobbes’ difficulties concerned irrational numbers, which tended to surface during advanced mathematical exercises. Irrational numbers are numbers which cannot be expressed as the ratio of two integers; for example π, but not the infinitely recurring 0.66666, which can be expressed as 2/3. Hobbes was against them, while more adept mathematicians had no problem acknowledging both their existence and their importance.

Hobbes experienced equal discomfiture at certain discoveries in the physical world. The philosopher’s false reasoning concerning the dimensions of Saturn’s ring earned him a sharp rebuke from Huygens: “M. Hobbes is about as a good a geometer as Jos. Scaliger,” he observed. (That sixteenth century French scholar had insisted that the square root of ten (3.16 etc) was precisely equal to π.)

In one of his greatest collaborations in physics, Huygens worked on the air-pump with Robert Boyle and others at the Royal Society. This was a device theoretically able to generate a vacuum, which raised both theological and political issues for Hobbes: if God pervades all space, so Hobbes reasoned, then any space left truly empty, as a vacuum, might be filled by the Devil. Therefore such a space could not be permitted to exist. Those actually working with the vacuum tended towards a more pragmatic approach.

Bayle & Locke

Relations went somewhat better with another non-scientist, the Huguenot philosopher Pierre Bayle. Already known to Huygens from his years in Paris, Bayle fled to Rotterdam after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Admitting his naiveté in the field, Bayle had asked Huygens what instruments were necessary to estimate parallax in order to judge both the real and apparent positions of stars. In 1691, Huygens wrote to him: “You are not like the majority of philosophers who take advantage of the discoveries of Astronomers without knowing how they were made.” Apprising himself of the state of the science did not always help Bayle, however. His entirely rational and well-informed ideas about comets, for example, were met with clerical protests that even in liberal Holland led to his pay as a professor being suspended for a time.

The year before, Huygens had sent out copies of his newly published Treatise on Light to scientific colleagues as well as to Bayle, Leibniz, and John Locke. The work was a summation of a lifetime’s thinking about the nature and behaviour of light, and predated Newton’s Opticks by fourteen years. Locke responded by sending Huygens his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, also newly published. Huygens read it “with much pleasure, finding there a great sharpness of mind, with a clear and agreeable style, which not all those in that country [England] possess.”

The Dutch scientist had met Locke briefly when he visited London following the Glorious Revolution which led to the accession to the English throne of the Dutch king William III in 1689. Huygens later wrote that he was vexed not to have gotten to know Locke better, as they would have had much to discuss. Locke’s empiricism owed much to Francis Bacon, whose experimental method was followed by Huygens, and he was opposed to Cartesian a priori reasoning on scientific (observable) issues – the very kind of reasoning that had forced Huygens to abandon his youthful philosophical hero. In contradistinction to Descartes, Locke suggested that space was distinct from the bodies in it, while Huygens himself had postulated an early notion of relativity based on the idea that all object motion is relative to other objects, and that there is no fixed spatial frame of reference.

In the seventeenth century, it was, if not quite normal, then at least more usual, that scientists would mix with philosophers: scientists were then called ‘natural philosophers’, after all. But what did Huygens gain from interacting with these leading philosophical figures? The experience didn’t turn him ‘philosophical’: by the standards of his peers, his work remained remarkably grounded in the observable, physical world. But it may well have secured him in his worldview, particularly in the idea that work should be directed towards good and useful ends, and that any God surely “acts according to the immutable laws of nature”.

© Hugh Aldersey-Williams 2021

Hugh Aldersey-Williams is the author of Dutch Light: Christiaan Huygens and the Making of Science in Europe (Picador, 2020).