Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Happiness & Meaning

Looking for the Purpose of Life

Brian King says that life’s meaning is a question of purpose; but what is the purpose of human existence?

In the expression ‘the meaning of life’, people more often than not mean ‘purpose’ when they refer to ‘meaning’. The real question such people are asking is actually ‘What is the purpose of life?’.

Things which have a purpose are often created for that purpose, such as man-made artefacts. One could establish an analogy or comparison between life and tools. The purpose of a tool is present at or before it is manufactured. A garden fork has been made to help gardeners dig, a tap is made to control the flow of water, and so on. The maker of the object and the person who uses the object both know this purpose, and the correct use of the object is seen as being use in line with the maker’s design. However the object could be used differently – the tap could be used as a hook to hang something from, and in the hands of a psychopathic killer the garden fork could be used as a rather gruesome weapon. So the ‘purpose’ of an artefact has two major senses; its intended use at the point of design and creation, and its intended use at the point of use. The latter may also be described as a misuse.

In these examples we see the purpose of something as being the deliberate, conscious purpose of either its designer or user. The question is whether, or which of, these analogies applies to our lives. Are our lives ‘given to us’ to be used in the ‘correct’ manner in the light of the manufacturer’s instructions, so to speak? Or can we create our own purpose at the ‘point of use’ – as we live our lives? Another problem is whether we can meaningfully apply the language of dealing with tools and designs to a different subject entirely, human lives. Are we stretching the use of these concepts into inappropriate areas? Perhaps even more importantly, in the analogy of life with tools are we assuming what we are trying to prove – that life has any ‘use’, that is, meaning? And if we take the analogy of life and tools literally, are we therefore assuming that there must be a designer? The analogy could end up being a circular proof for the existence of God – ‘lives are designed for a purpose, therefore there must be a designer’ – but circular proofs don’t prove anything, since they assume what they’re trying to prove. We should maybe try a different analogy.

Natural Purpose

In biological terms, organs are also described in terms of their purpose, although we usually substitute the word ‘function’, as in the function of the eye or the liver. We also talk in similar terms when referring to the connections between plants and animals; for instance we talk about the purpose of bees being to pollinate flowers, or the purpose of some kinds of bacteria being to help dead matter decay and rot down, and so on. The Ancient Greek anatomist Galen (129-200 AD) was so impressed by the omnipresence of function or purpose in nature that he thought it a kind of demonstration that everything worked according to a grand cosmic plan designed by God. In fact, by the Middle Ages in Europe, this attribution of design had spread to human society, so that everyone was seen to have their place in the social order, which was seen as sacrosanct since it was designed by God. Therefore the purpose of life for man involved acceptance of their (for the most part lowly) station in society, with a rewards to come later in heaven if they fulfilled their allotted function.

The idea that everything in nature harmonises in an interplay of mutually supporting functions and purposes set by the grand designer contributed to the ‘design argument’ for the existence of God. However, that idea received a major setback when Darwin formulated the idea of evolution through natural selection in The Origin of Species (1859). The implication is that things in the natural world only harmonise and operate together with each other because if they didn’t they wouldn’t have survived and reproduced. On this perspective, design in nature is an illusion in that there is no designer – only a blind process that necessarily produces circumstantially favourable for organisms.

Nevertheless, we do still talk about the design of organisms and their organs, and the way we do this sheds some interesting light on how we conceive purpose, since how we look at purpose is often connected to perceived importance. For instance, we say that the purpose of the bee is to pollinate the flower if we see the flower as the object of primary concern; but if we are, say, beekeepers, we would be more likely to say that the purpose of the bee is to produce honey to feed the hive. Here purpose can be seen to be relative to a larger context – carrying seeds for flowers, or producing honey for the hive – and is connected with exploiting or using something for certain ends. Yet in nature it is often not quite clear who is using who. Is the small bird that eats ticks from the hide of the rhinoceros using the rhino as a large self-service smorgasbord, or is the rhino using the bird as a means of ridding itself of annoying ticks? They both need each other. So purpose is relative, then, and relates to something’s or someone’s relative importance. It is fairly intuitive that the organs of a body are less important than that body, in that they serve the interests of the body. Therefore the function of eyes is to enable the organism to see; the eyes are serving the interest of something more important than them, the organism.

So, using this analogy, we could say that if our lives have a purpose, it consists in serving something bigger than us. Often we do feel that we should serve, say, our country in war time; we might even sacrifice our lives for a greater good. But, unlike biological organs, we have a choice – we can choose what to see as more important than us, or we can choose whether to see something as more important than us.

Purpose as Aim

We often do things for a purpose; but here the word ‘purpose’ means ‘reason’, ‘aim’, or ‘goal’. We do A to make B happen: we do our homework so that we can pass our exams. Why do we want to achieve B? To achieve C, of course. We want to pass the exams so that we can get to university. And why do we want C? To achieve D, of course, then E, F and G etc… We want to get to university so that we get a good degree, to get a better job…

Thinking in this way we either set up an infinite regress, or we have to stop somewhere and say that we want to achieve this thing X ‘just because we want to’, as an end in itself. Why do you want a good degree? To get a good job. Why? Money. Why? To buy things you want. Why do you want to get things you want? Because you want them. Why? It seems strange to ask why you want what you want – we want things in order to make ourselves happy, obviously. It seems then that the end purpose of all our subsidiary wants is to make us happy.

Is this then the purpose of life – to be happy? Here we have a purpose that’s serving our own interests rather than something more important than us. This sees man’s purpose as more embedded in human needs rather than as part of an overall scheme. Everything we do, all our choices and actions, serve the purpose of our life – to be happy.

This also clashes with the previous view in the sense that on this analysis we cannot say what the purpose of life as a whole is, only what the purpose of bits of it are in context. That is, we can say that all our desires and choices may be instrumental in making us happier, but this has no bearing on what the whole of life is for. And when we ask the question ‘What is the purpose of life?’, are we not referring to the purpose of all of it, not just of particular actions within it? This question is rendered particularly acute when we remember that all our aims, ambitions, and successes end up with us being dead.

So perhaps we are getting confused and using the language of biology or of artefacts for something – our lives – for which it isn’t appropriate. Perhaps it’s like talking about days of the week as though they were colours, or talking about the speed of beauty; it’s just nonsense, a category mistake. In the same way, perhaps it is nonsense to talk about whole lives, or life as a whole, as though these were the kind of things that could have purposes. It sounds reasonable to enquire into the point of life, but perhaps it’s a bit like asking the way to plastic? Plastic doesn’t have a direction in the same way that life doesn’t have a point. In such ways language can fool us, or so the argument goes. This is the kind of criticism that Ludwig Wittgenstein used to show how language taken out of its normal usage and context loses its meaning: the language game connected to purpose and function in parts of lives, is not applicable to lives as a whole.

Yet though this argument sounds reasonably logical, it misses the point that there’ s a very strong sense that ‘What is the purpose of life?’ is a meaningful question.

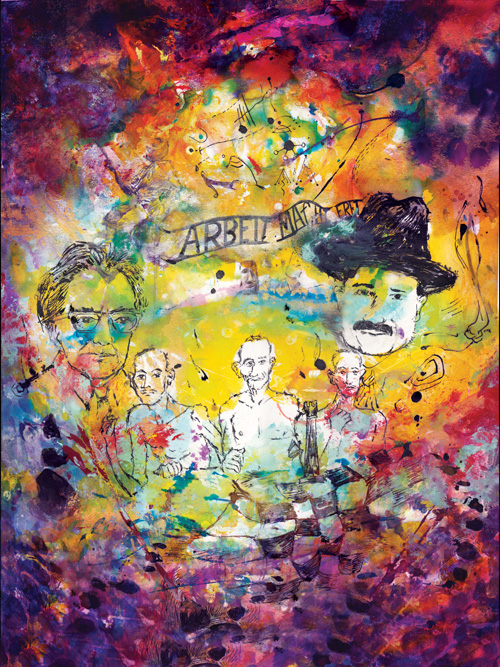

Questions of Purpose by Venantius J. Pinto, 2021

Image by Venantius J Pinto 2021. To see more art, please visit behance.net/venantiuspinto

So… Is There a Point?

The first type of purpose we considered, the kind handed down to us by a designer or other authority, would be the kind of purpose that would give our lives meaning, since it would be imposed on our lives from the outside. Religion, patriotism, family honour, being of use to God, or society, or even to some kind of totalitarian state, could all be seen as purposes ‘over and above us’. It would be comforting to know that there is something your whole life achieves; it would also effectively render us the tools for the purpose of the greater thing. Here the analogy with artefacts is clear. But just because it’s an attractive idea, that does not mean that it is true. How might it be criticised?

1) If you don’t believe in a God, or an omnipotent state or ruler, it’s difficult to see how this kind of externally-imposed purpose could work for us. Why should you accept anyone’s authority in making such a claim of purpose on your life?

2) Submission to a greater authority to some degree involves deliberately denying ourselves the responsibility to think for ourselves concerning issues of fundamental importance, such as our purpose in life, and the values by which we should live in order to achieve that purpose. Many philosophers (Jean-Paul Sartre particularly comes to mind) w ould argue that this surrendering of our will is denying the basic humanity of our existence, which is that we are free to choose and are inescapably responsible for our choices.

3) If we complete this purpose – if the purpose is achieved – then by definition we no longer have a purpose. For example, a person who sees that his life’s purpose is to attain eternal salvation is rendered purposeless once he has achieved that end. Is heaven full of people who have no sense of purpose? Furthermore, if a person saw the whole meaning of his life in terms of a given purpose and he achieved that purpose, he would cease to be the same person, in that what he regarded as the most basic point of his life would no longer apply to him. He would, it could be argued, have lost his fundamental identity.

We could formulate this syllogism:

-Either our purpose is achievable or it is not.

-If it is achievable then after it is achieved we no longer have a purpose.

-Then our lives would be futile.

-If it is not achievable then attempting it would end in failure, and to continue would be futile.

-Therefore, either way, our lives are ultimately futile.

One way of getting round this argument is to see the achievement of purpose not so much as an event but as an ongoing process. If we claimed that our purpose was to be rather than to do, we can never finish or complete it, and so we will always have that purpose. For example, if we claimed that our purpose was to have children to succeed us, then once we have done that, there’d be no more purpose. By contrast, if we claim that our purpose is to be good, we can always strive for that.

4) If nature can confer purpose on humans, then we should be able to ask in what context does that purpose operate? A bee’s purpose is in the context of making honey or pollinating flowers. This is a matter of choice of use from man’s perspective. Or the eye’s purpose is in the context of a complete organism. This is a given matter. Which of these two models fit the purpose of life? What is the greater natural context here, and is it a matter of our choosing what is important?

5) If it’s not a matter of choice and we say that nature just confers a purpose on us, we can always ask what the purpose of nature itself is. This argument can also apply to family, religion, or state; if our purpose is to serve one of these institutions, we can further ask what the purpose of the institutions are. It seems to me that from there we would often argue round in circles, explaining that these things are there for our purpose. There are similar arguments with God: He confers a purpose on us; but we can ask for what reason He does this.

6) Moreover, to accept that a purpose is a given makes us to a degree like automata that act according to perceived instructions. Again some would argue that this detracts from our dignity and freedom. The fact that we can always question given purposes would suggest that somewhere along the line we must make a choice whether or not to accept the purpose given.

All the above points seem to suggest that the idea that there is a given purpose to our lives is rendered incoherent either by our inability to understand the larger context or by our ability to question that purpose. In the end it all seems to be a matter of our choices. It could even be argued that it is choice which confers meaning and purpose in our lives – as indeed many existentialists do argue.

What Experience Tells Us

Perhaps we’re looking at the problem the wrong way round. Instead of wondering what the purpose of life is from the perspective of someone who cannot see what the point is, it may be worthwhile looking at the situation from the perspective of someone who feels that they do have a purpose.

In his novel Beware of Pity (1939), Stefan Zweig says, “It is never until one realises that one means something to others that one feels there is any point or purpose in one’s own existence.” To develop an argument for purpose based on feelings is dubious practice, since you could argue that anything that made you feel fulfilled constituted a purpose. This could include even the deluded obsessions of someone who felt fulfilled by incessantly tearing strips of paper evenly, or torturing small animals, or people. It makes fulfilling your purpose into the achievement of some kind of psychological disposition. To argue from experience we need something more than just feeling, then. Zweig’s statement does have some more validity, in that it is intended as a general comment about the human condition rather than a statement about a particular individual, and there is probably general agreement with it, too. The psychiatrist and philosopher Viktor Frankl in the preface to his memoir Man’s Search for Meaning (1946) wrote:

“Don’t aim at success – the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it. I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge. Then you will live to see that – in the long run, I say – success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think of it.”

The implication of this is not so much that the question ‘What’s the purpose of life?’ is meaningless, but that to ask it is inadvisable in a practical sense. On this argument, purpose, meaning, and happiness are by-products of life, and are not gained through being targeted. And according to both Frankl and Zweig, they occur because one sees something as more important than oneself. This can be other people, or a cause. Concerning other people, the phenomenon of being in love provides a case in point, or a mother’s love for her child; and with causes, such as a religion or patriotism, this perceived importance would explain the phenomenon of martyrdom. However, a counter to this would be an apparently deluded devotion to a person or a cause. Do we regard total obsession with, say, collecting bottle tops, as capable of really being the point of someone’s life? Or would we say that they’ve missed the point? More generally, if we see total dedication to something other than oneself as the key to finding a purpose in life, how do we discriminate between purposes that are worthy of the accolade ‘meaningful’ and those that are just ‘silly’? If it’s merely a matter of subjective judgment, then anything can count.

© Brian King 2021

Brian King is a retired Philosophy and History teacher. He has published an eBook, Arguing About Philosophy, and now runs adult Philosophy and History groups via the University of the Third Age.