Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Love & Romance

Spinoza & the Troubles of the Heart

Dan Taylor shows that even great philosophers can have their hearts broken.

Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) isn’t often read for his counsel on love. We do not know the extent to which he knew love, and his words on physical love tend to be distrusting and unsentimental. In a passage on jealousy, he gives this example of ‘love toward a woman’ – one of the few instances where women appear in his work:

“For he who imagines that a woman he loves prostitutes herself to another not only will be saddened, because his own appetite is restrained, but also will be repelled by her, because he is forced to join the image of the thing he loves to the shameful parts and excretions of the other.”

(Ethics Part III, Proposition 35 Scholium, 1677)

It is an unusually bitter, even broken-hearted formulation, in a writer otherwise characterised by a generosity of spirit and an affection for humankind. Such love as he describes always seems doomed to failure. If it does not end in infidelity and deception, then it otherwise distracts from the solitude appropriate for a philosopher (who, like many others in this period, neither married nor had children, or to our knowledge had any significant romantic relationships – except one, which we will come to…).

In the Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect (1662) – one of the best places to get first acquainted with Spinoza’s famously difficult philosophy – Spinoza speaks with a sense of loss about how he came to embrace the philosophical life:

“After experience had taught me that all the things which regularly occur in ordinary life are empty and futile, and I saw that all the things which were the cause or object of my fear had nothing of good or bad in themselves, except insofar as [my] mind was moved by them, I resolved at last to try to find out whether there was anything which would be the true good, capable of communicating itself, and which alone would… continuously give me the greatest joy, to eternity.”

Both here and in the Ethics, the danger of love seems to not be in loving itself, but in the importance it grants to a person and a relationship that is necessarily uncertain and constantly eddied by change. The lover may love the beloved intensely, but the beloved may one day cease to feel the same or might choose to love another. Moreover, love pulls us in and captivates us, its manic babbling overwhelming rational inquiry and the mundane work of everyday life. Only later, buried in some technical definitions, does Spinoza leave open the possibility for romantic contentment. Marriage, he thinks, could agree with reason in some cases, so long as physical union is ‘not generated only by external appearance’, but also by a ‘love of begetting children and educating them wisely’, and by a love caused by ‘freedom of the mind’ (Ethics Part III, Definitions of the Affects 20).

But these moments take on a kind of shading with later formulations. Students of Spinoza’s politics will know that at the end of his unfinished Political Treatise (1676), Spinoza excludes women from participating in his ideal democracy on account of their purported natural weakness. While Genevieve Lloyd and Beth Lord have credibly reconstructed a feminism in Spinoza by way of the earlier Ethics, in which women are weaker not by their essential natures but by historical and sociopolitical circumstances, these remarks present a challenge to easily reclaiming Spinoza as ‘one of us moderns’.

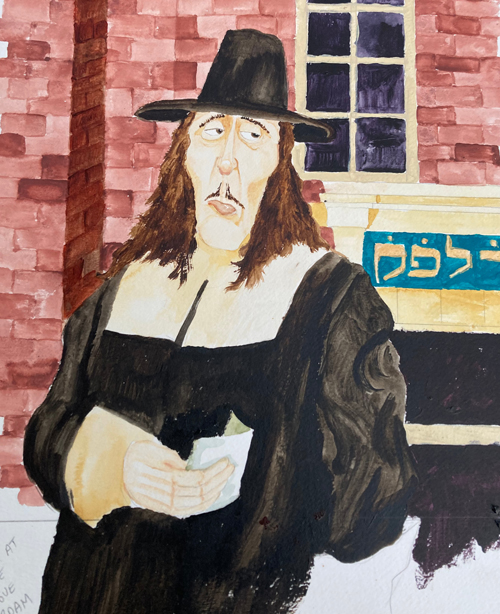

Spinoza's Broken Heart by Stephen Lahey 2022

Love Madness

Early biographers of Spinoza speculated that his heart was broken in his early twenties. Johannes Colerus, a Lutheran pastor and near-contemporary of Spinoza who undertook the first biographical research into him, interviewing his former landlord and associates after his early death in 1677, claimed that Spinoza had been rejected by Clara Maria, the daughter of his Latin teacher, Franciscus Van den Enden, after she’d fallen in love with another student. More recent biographies have attempted to scotch that idea, suggesting that the age gap was too great, making the proposition unlikely. But a recent excellent biography of Spinoza by Maxime Rovere (not yet translated into English) muddies the waters. Clara Maria was sixteen when she met a twenty-three-year old Spinoza. She was helping her father to teach Spinoza Latin, and possibly co-starring in the elaborate tragedies and love stories Franciscus would stage to public audiences.

Beyond gossip, speculation, and the self-defensiveness of the text, where else might we turn to understand the troubles of Spinoza’s heart? We could look at his references to poetry and literature.

In his Theological-Political Treatise (1670), a book in which he radically critiques Biblical authority (and which earned the impressive sobriquet from one opponent as book 'forged in Hell' by the Devil himself’), Spinoza draws upon a text well-known throughout sixteenth and seventeenth century Europe for its ironic treatment of love, Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1532). In this complex epic poem we follow the journey of the knight Orlando, who falls in love with the pagan queen Angelica. Orlando’s love is spurned when Angelica falls in love with another knight, and as a result he goes mad, rampaging across Europe and Africa until his friend Astolfo travels to the moon to literally recover his senses. In the Theological-Political Treatise, Spinoza cites this text as an example of where it is important to know the motives and context of the author in order to understand strange or incomprehensible things:

“I know I once read in a book that a man named Orlando the furious used to ride a winged monster in the air, that he flew over whatever regions he wanted to, and that by himself he slaughtered an immense number of men and giants. The book contained other fantasies of this kind, which are completely incomprehensible from the standpoint of the intellect.”

(Chapter VII, paragraph 61)

In a provocation that seems to have gone unnoticed, Spinoza then compares this with Perseus in Ovid, whose winged sandals helped him slay Medusa, with Samson’s slaughter of a thousand Philistines with the jawbone of a donkey (Judges 15:15), and Elijah’s burning chariot that flew to heaven (2 Kings 2:11): “These stories, I say, are completely similar.” Only their context and purpose separate them.

While these remarks are laced with his usual caustic wit, they also indicate the value of fiction in Spinoza’s thinking. An inventory of his book collection at his death contains a surprising amount of literature for a philosopher with a reputation for austere metaphysics. Much of it is in Spanish, the language of learning in the Sephardic community he grew up in – including Cervantes, Quevedo, and Gongora. Spinoza’s own works are studded with references to Latin poets and playwrights such as Ovid and Terence.

Terence’s Eunuchus in particular deals in the troubles of the heart. Spinoza knew this play well. It’s thought that as a young man he acted in a public production staged by Franciscus Van den Enden perhaps starring his daughter. He alludes to it later in Ethics Part V, where the theme of the unfaithful lover returns: “So also, one who has been badly received by a lover thinks of nothing but the inconstancy and deceptiveness of women, and their other, often sung vices. All of these he immediately forgets as soon as his lover receives him again” (Proposition 10 Scholium). This seems to be riffing on the first scene of the play, in which the lovestruck protagonist, Phaedria, despairs after being ejected from the house of Thais, whom he hopes to seduce. Parmeno, his plain-speaking slave, warns his master about the consequences of losing his wits, then offers advice on the drama and dangers of love: “In love there are all these evils: wrongs, suspicions, enmities, reconcilements, war, then peace; if you expect to render these things, naturally uncertain, certain by dint of reason, you wouldn’t effect it a bit the more than if you were to use your endeavors to be mad with reason” (Eunuchus, I.i).

Spinoza has a lot to say about the challenge of trying to make what is uncertain certain. It crops up in the Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect when he asks whether he might be ‘willing to lose something certain’ – the life of the mind – to gain the ‘uncertain’ existence of sensual pleasure, riches and honour. It’s foundational to the Ethics Part IV, which outlines a science of the emotions that’s also a physics of the emotions, dealing with their power, force and causality. Like the drunk, the wailing toddler, the chatterbox, and the lunatic, the lovesick person is one of several dramatis personae who appear across Spinoza’s colourful works. The lovesick suffers a particular kind of madness, losing control of both body and mind. It’s less the divine, inspired ‘madness of love’ of Plato’s Phaedrus and Symposium, or the romantic, dizzying l’amour fou of André Breton and the Surrealists, than something closer to being kidnapped. Parmeno warns Phaedria of this ‘captivated’ state and, pleads with him to like someone sold into slavery, “redeem yourself… at the smallest price you can”: to pay the ransom, and avoid falling any further in love.

Remarks about the madness of love, the absurdity of chivalry and the like were common in the sixteenth century. Cervantes’ Don Quixote is the knight who tilts at windmills in his fight for Dulcinea del Toboso, a non-existent princess. Shakespeare’s works bristle with the folly of love, a ‘madness most discreet’. The ‘star-cross’d lovers’, Romeo and Juliet, also labour under the spell of a powerful delusion, in a kind of servitude. It’s a pressing issue of desiring what, in being impossible, harms us with delusions of attractiveness or grandeur that easily become passions of jealousy, hatred, and vengeance.

Love, defined deceptively simply by Spinoza as ‘joy with the accompanying idea of an external cause’, has been wrongly overlooked by his readers. For Spinoza, love and desire are at the heart of human power. Yet, as Spinoza’s account also makes all too clear: it’s complicated.

© Dr Dan Taylor 2022

Dan Taylor is a Lecturer in Social and Political Thought at the Open University.