Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Classics

The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt

In our ‘classics’ department, James Reynolds says we mustn’t forget Hannah Arendt’s warning.

“Totalitarian solutions may well survive the fall of totalitarian regimes in the form of strong temptations which will come up whenever it seems impossible to alleviate political, social, or economic misery in a manner worthy of man.” – Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was first and foremost a polemicist, driven by a faith in truth and honesty even when her conclusions may make us uncomfortable. Yet over seventy years since it was first published, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) still holds weight in our political climate, retaining its significance in its message of responsibility. Above all, we must remember our own role, however slight, in moving society forwards.

Placing Arendt

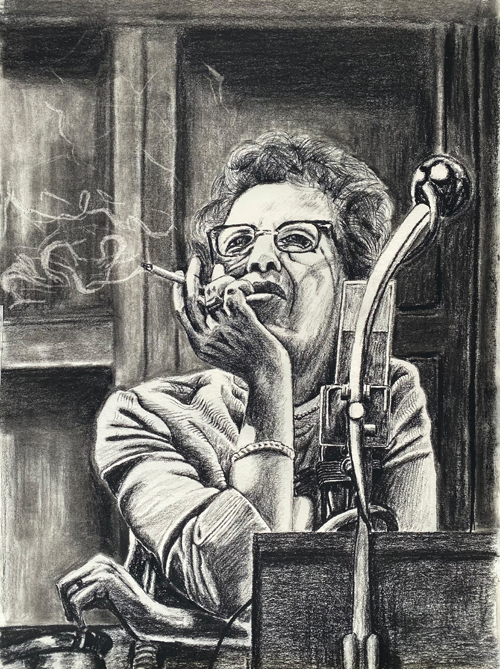

Hannah Arendt in 1933

Hannah Arendt was a practical philosopher. The theoretical philosophy of the Greeks had attempted to answer questions of knowledge, logic and metaphysics. The moral philosophies of the Middle Ages through to the Enlightenment looked to codify the right way to be. But the practical philosopher develops her work from a pressing need to act.

Born in Hanover in 1906 to secular Jewish parents, Arendt’s worldview was soon marred by war and ostracism. As a PhD student, her academic work touched on the theme of love in the writings of St Augustine. In 1924, while at the University of Marburg, she fell for the phenomenologist Professor Martin Heidegger, who she saw as the manifestation of an original love for philosophy. Arendt’s later work is shaded by these rosy formative years. In 1933 Heidegger joined the Nazi Party, and was slow to distance himself from it even after the war – a position that would understandably strain his relationship with Arendt. In The Origins of Totalitarianism she struggles with the idea of a mob unable to see its wrongdoing, unable to frame its victims as thinking, living human beings.

As she escaped from the war to the US via France and Portugal, she noted the delicacy of human rights. The ‘natural rights’ born from the French and American revolutions had been lost in the refugee camps of the Paris suburbs.

Don’t Let History Repeat Itself

Practical philosophies emerge out of necessity. When Arendt published The Origins of Totalitarianism, the book carried with it a sense of urgency. In its early chapters, she reminds the reader that the atrocities of the twentieth century had not ended with the war. Although there may be a temptation to see the Nazis as an isolated phenomenon, the product of a few ‘bad apples’, Arendt reminds us how easy it was for many European populations to adopt the mob mentality that gave rise to extremism. Above all, her concern is that history has a tendency to repeat itself when we absolve ourselves of personal responsibility. If we believe that we would not have been complicit (or even active) in these movements, we may allow our own social behaviour to go unchecked. Arendt demands from her reader a personal investment in unlocking the true narratives behind Nazism and Stalinism. She asks, for example: if a culture of racism set the terms of Nazi rule, where did it come from? By reducing the complex history behind these movements to oversimplified excuses such as ignorance, we fail to be accountable for the past. So the book is structured into three essays: on antisemitism, on imperialism, and finally on totalitarianism.

A key takeaway from The Origins of Totalitarianism is the value of stepping back. In her description of the conditions that gave rise to the Nazi Party, Arendt is admirable for her humanisation of those with whom she contends. Her discussion of imperialism tries to really understand the motivations and incentives that legitimised each new system of oppression and exploitation. Since we are all fallible, she seems to be saying, it is proper to think critically and constructively about our history, avoiding the temptation of simply looking down on those who got it wrong.

Arendt’s commitment to telling her truth regardless of the implications for her reputation is her most outstanding feature. The Origins of Totalitarianism made Arendt an overnight success, but offended some communities by its implication that Jewish leaders had been partly complicit in the Holocaust through their complacency. Commentators found Arendt’s conclusions to be dismissive of those who had suffered at the hands of the Nazis, and had faced impossible choices. Only six years after the end of the war these wounds were still very raw. Similarily, in 1963, her essay ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’, published as a series in the New Yorker, resulted in her near-total exclusion from social and academic circles for her claims about ‘the banality of evil’. People wanted to believe that the Nazis were a monstrous abberation who could never come again. She suggested that most were ordinary conformists and followers; the kind of people we can find all too easily in any time.

Arendt wrestled with the truth because the alternative was to allow reality to become blurred by what’s comfortable. In such blurring, totalitarian movements thrive. For Arendt, a key feature of totalitarianism - in contrast to other forms of tyranny or dictatorship – is the toying with truth, deliberate confusion of fiction and reality, and incessant use of mass media to manipulate the way millions of people experience the world. In our era of fake news, targeted messaging and ‘cancel culture’, there is still something profound in this warning. Arendt is alerting us to the use of propaganda and conspiracy to change the perceived structure of reality on a whim.

A central worry is that these conditions emerge by our own hand. It is, for Arendt, the failure to engage critically with our own ideas that draws us into an echo chamber of isolation, detached from the world, and so paving the way for radical ideology. Written at the height of opposition to the Vietnam War, her later work On Violence (1970) dispels the myth of utility in violence. Better to engage intellectually with our opponents, to try to understand the root of conflicting narratives, than to rely on chaos to shake up ill-placed power. We still ask whether it is better to seek punitive or reformative measures against those with views we find abhorrent. Even in today’s social media culture wars, we might worry that a lack of proportionality in ‘cancelling’ those who ‘get it wrong’ gives offenders no way back into the conversation, forcing them instead to develop their views in the mobbish worlds of underground internet forums, detached from the narratives of polite society.

Hannah Arendt portrait by Athamos Stradis

Conclusions

In an era that prioritises quick, efficient content, it can be difficult to read Arendt in context. But in 2021, The Origins of Totalitarianism stays relevant as a reminder of how easily we can be led astray by following the crowd. The Origins of Totalitarianism sought to move beyond looking at history in stark black and white. There is a sense of duty, an urgency, to describing the shades of grey. Even now, Arendt’s message to think properly about where we get our information from and to challenge our expectations from time to time, applies. She teaches us to look at history as the result of unique and complex conditions. For this reason, it is difficult to draw out the conclusions of the book for the modern age. But Arendt wants the reader to reflect on the circumstances that have created their views, acknowledge their own fallibility, and to open up to the possibility of having it all wrong.

Though demanding, Arendt is patient with her readers. Concerned with how easily we may be sucked into bad ideas, The Origins of Totalitarianism is sensitive to the fractured thinking of human beings in any era or circumstances. Seventy years on, Arendt’s philosophy is relevant because it tells us about ourselves, and the role we must play in forging history, for better or for worse. Today, the book is important as a warning of our tendency to choose simple narratives when other ideas may seem daunting or implicate us somehow. Arendt does not divide the world so neatly into ‘oppressor’ and ‘oppressed’. Instead, she invites readers to a path of redemption. Just as her early philosophy is one of love which focuses not on the suffering of the past but the promise of the future, there remains an optimism in her work that human beings can become good when we choose to be.

© James Reynolds 2022

James Reynolds is a journalist specialising in European history and politics, and teaches political philosophy to young people across London.