Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Golden State Killer & Deleuze’s ‘Dividual’

Angela Dennis computes the use and abuse of digital data.

In June of 2020, the infamous Golden State Killer was finally brought to justice. From the late 1970s to the early 80s he had terrorised neighbourhoods in California, creeping into homes at night and robbing, raping, and often killing their occupants. Police had few leads, the trail went cold. Then in 2018 investigators put a sample of DNA found at one of the crime scenes into a genealogical database called GEDMatch. GEDMatch was not designed to find criminals, it was intended to help people find people they were related to. It worked by making connections between the DNA sequence data of its members. The user, by entering their DNA sequence into the website, would be given information on likely relatives who were also members, creating a possible family tree. When investigators put the Golden State Killer’s DNA into the database, the system offered up some close matches – possible distant relatives of the suspect. This material, painstakingly triangulated with previously known information, allowed investigators to narrow their focus down to one person, Joseph James D’Angelo, who by then was an old man of seventy-two years. The police had found their killer.

The Golden State Killer, finally brought to justice

Joseph James D’angelo © Sacremento Sheriff’s Office 2018 Creative Commons

After three decades of evading capture, eluding brilliant investigators, D’Angelo was caught by the brute power of mass data and algorithms, and he never saw it coming. This merging of forensic science and genealogy has now become a massive success, kicking off the burgeoning field of ‘forensic genealogy’ and leading to the resolution of over sixty other cold cases.

D’Angelo’s capture offers some solace to his living victims and the families of the deceased. But this case has wider implications – it reveals the power of the web of ever-increasing digitised data about each of us, which may be classified, parsed up, separated, and recombined ad infinitum, and which is able to be used, and is being used, in a myriad of unknown and unknowable ways, both for and against us. This bears real implications for privacy, agency, control over our own lives, and the human experience of living. D’Angelo discovered this to his detriment, when biological information he left behind in the late Seventies placed him in a prison cell in 2020.

It is almost impossible in today’s world to avoid offering up data about oneself to organisations, corporations, and governments. We may do it knowingly for a specific reason, such as when we deliberately send genetic information to a genealogy website in order to find family members, or when we offer the same data to a medical organisation to learn our propensity for particular diseases. But even when we provide our information to organisations or governments for a purpose, with our advance knowledge and consent, we may not know all the ways in which the information may be used, including ways which we never intended (who reads those user agreements, anyway?). In fact, D’Angelo’s case generated heated debate within the normally genial community of genealogists, with many declaring this new partnership with law enforcement to be a betrayal of trust.

There is also the data which we reveal inadvertently whilst in pursuit of another goal. For example, in using the Google map function on our smartphones, we may provide Google with information as to our place of work, favourite pastimes, common ways of travel, and even our relationships. A web search by us may offer the search engine’s controllers information on our likes, dislikes, future plans or problems. Online purchases reveal our buying history and patterns. Then there is the data which is recorded without our knowledge or involvement, such as in satellite tracking of GPS positions. Simply put, a revolutionary change has occurred, such that many of the basic activities of everyday life which we have engaged in for millennia now entail the offering up of data to various organisations. Merely travelling, communicating with friends, buying food and clothing, listening to music, because of the digital media through which they are performed, are creating a data picture of each of us, stored in a myriad of memory vaults.

Deleuze in the Digital World

Well, what of it? So Facebook has photos of me. Is this a cause for concern? Is it benign or malign, or neutral?

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze died in 1995, but his concepts of the ‘Dividual’ and the ‘Control Society’ offer a way to understand the changes which enabled D’Angelo's capture, and their possible implications for life in the Twenty-First Century. In his 1990 piece, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, Deleuze suggests that humans have moved from a discipline-through-laws society in which a human was seen as an individual (as contrasted with a mass), towards a society of continuous control and surveillance in which the human has become ‘dividual’ – parsed into various informational units. He states, “We no longer find ourselves dealing with the mass/individual pair. Individuals have become ‘dividuals’, and masses, samples, data, markets, or ‘banks’.”

For Deleuze this is a new kind of power structure, characterised by a form of control of people which is less visible but more continuous: surveillance through data. It may on one level seem more freeing, but it is perhaps simply more flexible. As he states, “the different [new] control mechanisms are inseparable variations, forming a system of variable geometry the language of which is numerical (which doesn’t necessarily mean binary). Enclosures are molds, distinct castings, but controls are a modulation, like a self-deforming cast that will continuously change from one moment to the other, or like a sieve whose mesh will transmute from point to point.” Yet like a mesh or mould, control of this kind seems total. Consider D’Angelo’s case – his own genetic data was not already in the database, but that of his distant relatives was. He was caught because of the DNA information of others, and because of the inherent connectivity of human genetics. An analogous situation arises with Facebook. Facebook, whose expressed purpose is connectivity, holds data on people who are not Facebook members (see A. Quodling at theconversation.com/shadow-profiles-facebook-knows-about-you-even-if-youre-not-on-facebook-94804). These ‘shadow profiles’ are born of the data of people who do use Facebook, from their email lists, photos, phone lists, etc. No one is an information island, and one cannot simply opt out of the control born of connectivity.

Deleuze stresses the continuity of control in the digitised world. To this I would add permanence. While matter eventually degrades, digital data can in theory be copied infinitely and kept forever. So, while D’Angelo’s original biological sample will degrade, the unique sequenced code representing his genome will endure. Likewise every message I have ever posted on Skype could theoretically be ready to re-emerge. Therefore, like D’Angelo, we all run the risk of having some piece of our data used against us later in life – of being faced with the inconvenient words and actions of a previous version of ourselves. We are already familiar with this: politicians are regularly apologising for past tweets or Facebook posts.

The resurrection of previous embarrassing behavior may not be totally new – consider Bill Clinton’s “I did not inhale” – but in a world in which so much is recorded and kept digitally, this phenomenon must accelerate. There can be no disappearance, no forgetting. The theorist Gerald Raunig captures the timelessness in this way: “These enormous multitudes of data want to form a horizon of knowledge that governs the entire past and present and so is also able to capture the future” (Dividuum, p.116, 2016). This also raises the question of how humanity might change in such an environment. Perhaps we will become more cautious in sharing something which may one day harm us; or perhaps we will become inured to or forgiving towards people’s shameful secrets.

The prospect of an accessible, almost complete recording of one’s lifetime digital communication recalls a previous seismic change in human experience – that of the invention of the mass-produced mirror. An accurate representation of our appearance may not be so different to an accurate recording of a lifetime’s worth of communication. Ian Mortimer argues that the invention of the silver-glassed mirror in 1835 brought on a ‘new individualism’. He states,

“The very act of a person seeing himself in a mirror or being represented in a portrait as the center of attention encouraged him to think of himself in a different way. He began to see himself as unique. Previously the parameters of individual identity had been limited to an individual’s interaction with the people around him and the religious insights he had over the course of his life. Thus individuality as we understand it today did not exist: people only understood their identity in relation to groups – their household, their manor, their town or parish – and in relation to God.”

(Millennium: from Religion to Revolution: How Civilization has Changed over a Thousand Years, 2016)

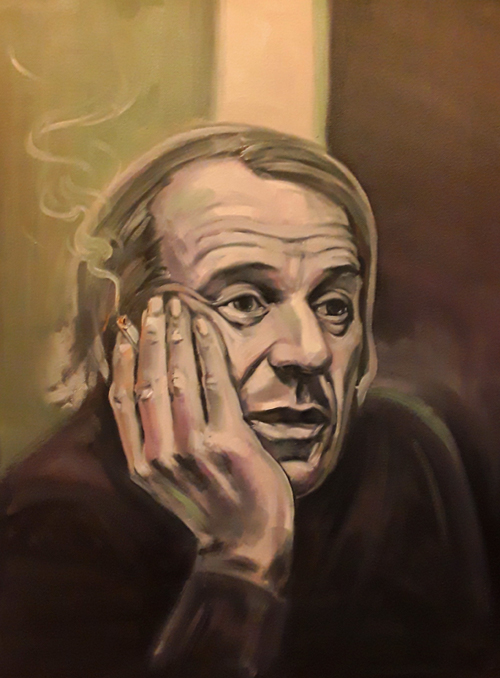

Gilles Deleuze by Woodrow Cowher 2022

Gilles Deleuze © Woodrow Cowher 2022 Please visit woodrawspictures.com

No More Free Agents?

There is not just the risk that our own data will be used against us, there is also the potential for aggregated mass data, processed though complex algorithms, to be used as a tool for control. Mathematics professor David Sumpter describes algorithms as a way of converting our data into an automated decision about us. Professor Sumpter warns, “The average person nowadays increasingly has their lives if not controlled, then at least curated by more than half a dozen algorithms every day” (from ‘The algorithms that control your life and the one thing that you really should be worried about’, The Daily Telegraph, 25th April, 2018). A familiar example is the ‘filter bubble’, which filters search engine results based on our previous searches. And Cambridge Analytica famously attempted to use a ‘personality algorithm’ to target and tailor information to voters during the 2016 US Presidential election.

Evident here are issues around human agency and decision-making. If, for example the news we receive is tailored towards views with which we already agree, our perception of the world may become skewed and our ability to make good decisions may be impaired. Mark Hansen takes this loss of decision-making control a step further, arguing that agency itself is becoming dispersed into cyberspace. He states, “through the distribution of computation into the environment by means of now typical technologies including smart phones and RFID tags, space becomes animated with some agency of its own… When ‘we’ act within such smart environments, our action is coupled with computational agents whose action is not only (at least in part) beyond our control, but also largely beyond our awareness” (‘Engineering pre-individual potentiality’, Substance 41(3), 2012, p.33).

This captures well the invisibility and flexibility of the digital control society described by Deleuze, as well as our perception of having agency but lacking it in actuality. However, the difficulty of this approach is that it seems to obscure the human agent behind the algorithm, even though we’re not yet at the point where the algorithm has no master. Moreover, if we are ceding decision-making power, then it would appear that we are doing so willingly. Thinking again of D’Angelo’s capture, the all-important genetic data was not forcibly taken, but freely given to the genealogical platform. Likewise, we freely offer up our photos to Instagram, our friendship networks to Facebook, and our home addresses to Uber. The generalised control we are subject to in the ‘control society’ even appears to be comfortable. It may even be pleasurable – until the leash suddenly tightens.

Most readers will be familiar with the self-satisfied boost one feels when a post on Facebook is liked. This and similar phenomena have been studied by psychologists M. Mauri et al, who found that Facebook can evoke a ‘‘psychophysiological state characterised by high positive valence and high arousal” (‘Why Is Facebook So Successful?’, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(12), 2011). These findings are consistent with Raunig’s thinking. He suggests that the human in the modern world has developed new appetites and desires which cohere it to the society of control: “The pull of machines, their attraction, has undoubtedly led to new, very bodily desires, to relations of appending, treating and enveloping… The desire to be online, for instance, has aspects of being permanently reachable, Internet addiction and apparatus fetishism at the same time. There is also an urge for increasingly strong haptic techniques of streaking, swiping, stroking” (Dividuum, p.109). This image of the human-technology relationship in the control society appears almost erotic, and certainly addictive.

Is It All So Bad?

Bodily compelled, attention-divided, sated by a false illusion of choice, embedded in a total data-web and looking towards a captured future, humanity would appear to have nowhere to turn. Yet seeing the sheer relief and joy on the faces of D’Angelo’s surviving victims, one must wonder if perhaps this new society of control has its compensations and liberations. Restorative justice, improved health knowledge, better contact with loved ones, work flexibility, increased mobility – these are just a few of the ways in which big data connectivity appears to have opened up unforeseen options. Indeed, a society in which rapists and murderers are much more likely to be caught for their crimes may open up new safety and freedoms too, especially for women and children. The harsher elements of the control society may yet be tempered by new norms, just as the use of forensic genealogy is currently forming new ethics and codes of conduct to manage its new powers. Likewise, ‘Rights to Privacy’ and similar calls may curtail the outsize influence of social networks. Perhaps, like the advent of the mass-produced mirror, this new paradigm will also open up new avenues for authenticity and individuality, not yet imagined.

There’s no going back, but I agree with Deleuze when he says the control society is no worse nor better than the disciplinary society: “There is no need to ask which is the toughest or more tolerable regime, for it’s within each of them that liberating and enslaving forces confront one another.”

© Angela Dennis 2022

Angela Dennis is a writer and researcher in Melbourne with a particular interest in issues relating to science, economics, culture and law. angeladennis.journoportfolio.com