Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

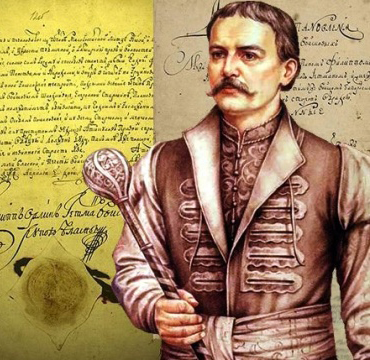

Pylyp Orlyk (1672-1742)

Hilarius Bogbinder tells us about an innovative Ukrainian philosopher, democratic theorist and campaigner against tyranny.

Chances are that you have never heard of Pylyp Orlyk (1672-1742), or perhaps any other Ukrainian philosopher for that matter – Gregory Skovoroda (1722-1794), perhaps? Anyway, you should have; for Orlyk, a Cossack politician, was the first to establish a democratic standard for the separation of the executive, the legislative, and the judicial branches of government. If you’re American, you may be familiar with James Madison’s conclusion in Federalist Paper 51 (1787), that “The structure of the Government must furnish the proper checks and balances between the different departments”; and if you’re European you might have read Charles Montesquieu’s famous dictum from The Spirit of the Laws (1748) that “When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty.” These deep and insightful arguments made a lasting contribution to political and legal philosophy. But they were not original. They were first pioneered not in Paris or in Philadelphia, but in Poland by exiled thinker and politician Pylyp Stepanovych Orlyk. He did so in 1710, in a document which in Ukrainian is known as Konstytutsiya Pylypa Orlyka – simply, Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution. Its rather long and tongue-twisting actual title was Pacta et Constitutiones Legum Libertatumque Exercitus Zaporoviensis – roughly translated as Agreements and Constitutions of the Laws and Liberties of the Army of Zaporovia. As was usual for the time, the document was in Latin.

We know relatively little about Orlyk’s life but what little we can find in the annals suggest that he was more than a mere politician. He began as a student of philosophy at the National University of Kyiv, Mohyla Academy. In one of the few biographical sketches written about him, ‘General Characteristics of Pylyp Orlyk’ (B. Krupnvtskyi, Annals 6, 1958), we learn that “Classical authors such as Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny, Virgil, etc., were very well known to him… His scholarly interests lay more or less in the realm of theology, history and politics. He was interested in legal problems as presented by contemporary authors. As a politician he derived his knowledge of world events from French, Italian and Dutch newspapers.” After his studies he became an advisor to the so-called ‘ Hetman’, Ivan Mazepa. The Hetman (‘chief’) was the elected leader of the Cossacks.

Perhaps unknown to many, in addition to being excellent horsemen the Cossacks were a remarkably democratic and egalitarian lot. It is worth understanding a bit about them to fully appreciate Orlyk’s thoughts. Their name comes from the old East Slavonic word Kozak, which means ‘free men’. This was fitting. Originally, they had been a loose band of former serfs who roamed the plains, but they gradually developed remarkably democratic institutions. A study of them emphasized that “Don Cossacks constitute the only society in Russia that managed to build a democracy during the 16th and 17th centuries… All questions were debated and decided in the assembly called Club of the Don Army, where each Cossack had a place with a right to speak and to vote. All leaders were elected by the Club” (The Fabulous Fate of the Don Cossacks, Vladimir Kostov, 2011, p.265). So in the sixteenth century, while Russia was sinking into tyranny under Ivan the Terrible, the Cossacks were experimenting with democracy, pluralism, and egalitarianism in a way that at the time can only be compared with the Swiss Cantons and the Italian city states. Yet they were not able to fully decide their own affairs. In the Treaty of Pereyaslav (1654), the Ukrainians had pledged allegiance to the Muscovite Tsar (though apparently the original document got lost!). This agreement gave the Ukrainians relatively extensive autonomy while formally being under Russian suzerainty. It wasn’t optimal, but the Ukrainians had little choice.

Image © Venantius J Pinto 2022. To see more of his art, Please visit behance.net/venantiuspinto

Their relatively peaceful relations with the Russians were to change. Orlyk was right at the centre of things when it happened.

Tsar Peter the Great (1672-1725) was unhappy with Mazepa as Hetman; and when Mazepa learned that the Tsar intended to remove him, he entered into an alliance with the Swedish King Charles XII. At this time Orlyk was Mazepa’s aide-de-camp. He drafted his letters, and was instrumental in establishing an anti-Russian coalition. When his mentor died, Orlyk was elected as the new Hetman. However, soon after, the Russians subdued the Ukrainians, and Orlyk was forced to flee to Poland, where his Constitution was drafted. He then travelled onto Sweden. He later lived in Thessaloniki, then governed by the Ottoman Empire.

In exile, he devoted himself to philosophical pursuits and correspondence in Latin, French, Polish, and Ukrainian. All his letters were duly transcribed into his notebook, which is a treasure trove for historians. In these he chronicled, “the misbehaviour of his loutish servants, the local fare, his bag after a day’s shooting in the plains, [and] stories told him by tailors, interpreters and bodyguards, Jesuits, consuls, doctors, spies and the Turkish judges and governors” (Salonica: City of Ghosts, Mark Mazower, 2005, p.107).

Although leader of his country, Orlyk never saw it again. He died in Moldova in 1742.

The Constitution of the Constitution

None of Orlyk’s writings were as influential as Konstytutsiya. It’s important to stress that his constitution is not a legal document, like, say, Magna Carta or the US Constitution, but rather, a short essay on opposition to tyranny and on the principles of a state under democratic governance.

So what exactly did Orlyk write in it, and why was it so important? Orlyk is at pains to point out that “the good of the Fatherland is always privately and publicly debated, both in time of war and in time of peace” and that it was bad for a country when autocrats prevented the rulers’ decisions from being discussed (Article 6). This point is explicitly directed against autocratic government, and by implication, against Moscow. In dictatorships, as he wrote, “the autocratic powers have legitimized such a right by their own authority.” The remedy against this was to be democracy, with “distinguished, judicious and meritorious individuals elected to the general council” and a kind of Senate with members appointed by the elected Hetman. In the future, nothing should be decided “except by their authority without their will” (Article 6).

Countries with dictators are often characterised by corruption. Powerful individuals – maybe today we would call them oligarchs – would be likely to try to bribe the government. Orlyk, more than many other contemporary writers, was alert to this, and made provisions against it:

“The Hetman must not be guided by any gifts and favors and must not appoint anyone to the rank of colonel or other military or civil office in return for a bribe, nor assign anyone arbitrarily to these positions. That both military and civil officers, especially colonels, must be elected by a free vote and after the election, be confirmed by the Hetman’s authority.”

(Quoted in From Autonomy to Independence: The Evolution of Ukrainian Political Thought, Song Hong, 2019, p.64.)

This was only one of the ways in which Orlyk was ahead of his time. Many constitutions established written later contain provisions for impeachment – the removal from office of the President or leader. Such clauses were not part of the constitutional framework that John Locke drew up in his Second Treatise of Government (1689). Orlyk, however, was prescient enough to include it: “If anything is found in the actions of the Grand Hetman that is incompatible with the rights and freedoms of the Grand Hetman, or that is harmful to the State, then the Sergeant Major, the Colonels and the General Councillors shall be called to account by private votes or privately, if the necessity arises, to denounce him” (Art. 6). But Orlyk is equally clear that the Hetman should not resign before due process has been observed. Indeed, while being tried, “the Grand Hetman should not repent”, but equally, neither should he “take revenge, but should, instead, try to rectify the deficiencies.”

Constitutional Conclusions

Like all documents, Orlyk’s Constitution was written in a particular context. Documents cannot easily be transplanted from their native soil into foreign lands, nor are they easily adaptable across time. Much as we may admire great political minds of the past, such as Plato (429-347 BCE), Aristotle (384-322 BCE), or even Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), we do not enact their ideas in full. It’s the same with Orlyk’s constitution. Yet in many ways his Konstytutsiya transcended the parochial concerns of the early eighteenth century. Orlyk made it clear in his Introduction that the reason for writing it was prompted by the “the Moscow State, by its numerous guilty methods, which violated the rights and freedoms…” Maybe history repeats itself? Certainly, many of his compatriots in 2022 would agree with Orlyk’s assessment that “the Moscow State, being able to fulfil its evil intentions… always wanted to annex our towns to her provinces” (Introduction). And in addition to making stipulations about rules and the conduct of the Prince, Orlyk’s Constitution also makes political demands, some of which are eerily relevant today: “the lands under the rule of Moscow must be returned to the original territory” (Article 4). When Sweden returned the original copy of Orlyk’s Constitution to Ukraine in June 2021, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy told its parliament that “a Constitution is the last chord in the symphony of state formation” (Speech at the Verkhovna Rada, 28th June 2021).

Since the war with Russia started in February 2022, and indeed before, the Ukrainians have stressed that they’re a European country and a democracy under the rule of law. Reading Orlyk’s Constitution of 1710, we realise that Ukraine is not just part of the family of constitutional democracies, they founded this tradition. Maybe this is another reason to say “Glory to Ukraine!”

Sláva Ukrayíni!

© Hilarius Bogbinder 2022

Hilarius Bogbinder is a Danish-born writer and translator. He studied politics and theology at Oxford University and lives in London.