Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Interview

Rebecca Buxton

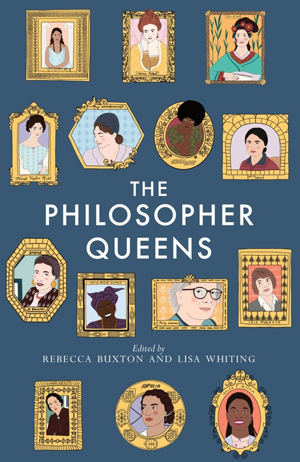

Rebecca Buxton co-edited, with Lisa Whiting, The Philosopher Queens: The lives and legacies of philosophy’s unsung women (2020). Reece Stafferton sat down with her to discuss the dilemmas women face, and have faced, when encountering philosophy, which throughout history has been dominated by men.

Women aren’t generally counted among the most famous philosophers. I challenged a friend recently: name five female philosophers. They couldn’t. Why are things like that?

In my experience, when you ask people to close their eyes and imagine a philosopher, they will usually think of a white man, usually in a toga or a turtleneck. Within this dominant caricature, it’s difficult to even imagine a woman philosopher, let alone name one. When we asked people in the street to name women philosophers as part of a promotional video for our book, we couldn’t find a single person who could name even one. And one of the people we asked told us that he was studying for a degree in Philosophy at a well-known London University college.

Why this is the case The list of reasons is of course long and complicated. Women were historically generally excluded from education, and therefore often didn’t have access to many of the sites of ‘accepted’ knowledge creation. And, moreover, even now, women philosophers, even within philosophy itself, are not as well-studied as their male counterparts. So, at least part of the reason for this failure is within academia itself. This is beginning to change with new projects that specifically highlight the contributions of women philosophers throughout history.

Furthermore, women who are more likely to be known – Simone de Beauvoir and Mary Wollstonecraft, for example – aren’t always thought of as ‘philosophers proper’, but as ‘feminist thinkers’. This relegation to other and often marginalised topics or disciplines is another reason why women are excluded from the title ‘philosopher’.

Why is there still a preponderance of men in philosophy?

I think the answer to this question has much to do with women’s exclusion from academia and also with the power of men in academia and society more generally. Women and other marginalised groups also face various other barriers to progression in academia. Women academics often have to deal with caring for others in their family, poor provision of maternity leave or childcare, precarious employment contracts, and much more.

Philosophy is also seen as a stereotypically masculine discipline. It may come as a surprise then that, at the undergraduate level, the gender split is nearly equal. Around 45% of philosophy students at university in the UK, for instance, are women! However, a big drop off happens on progression to further study for higher degrees. So it looks as if, although young women are stepping into philosophy at around age eighteen or nineteen, they are afterwards leaving it at a much higher rate than their male counterparts. It’s difficult to know why this is the case. Some people argue that the lack of women role models has a serious effect on whether women choose to continue in philosophy. Likewise, the lack of women on university reading lists might just cement the view that philosophy is really a ‘man’s world’.

Can you give us an example of men overshadowing women in philosophy?

One of the starkest examples of this, in my view, comes from the Edith Stein chapter in The Philosopher Queens, written by Jae Hetterley. I’m ashamed to say that I didn’t know who Edith Stein was until Jae decided to write a chapter on her.

Stein is well known for being a Jew who converted to Roman Catholicism and became a nun. She was eventually exposed as a convert during the Second World War, and was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. However, Edith Stein was also the second woman in Germany to earn a Philosophy PhD. Her thesis supervisor was Edmund Husserl, the founder of modern phenomenology.

As his PhD student and researcher, Stein was tasked with taking Husserl’s research notes on phenomenology and writing them up into publishable manuscripts, including Lectures on the Conciousness on Internal Time, which was eventually brought to press by Heidegger in 1928. Husserl did not provide a first draft – she wrote the entire piece herself from his rough notes, developing his ideas further as she went. But she was left uncredited for her work. As Hetterley writes in the chapter on Stein:

“It is difficult to ascertain how much of the work is Stein’s and how much is Husserl’s – but without a doubt, she deserved better. And all of this, we should note, was not even uncovered until the 1991 English translation appeared… In the end Stein’s academic career was stymied because of Husserl’s sexism – and later on, the Nazi’s racist legislation – but also because Husserl and Heidegger would not even credit her for the work that she did.”

In the same vein, why don’t we usually count queer and ethnic minority philosophers among ‘the greats’?

Again, this has a lot to do with historic exclusion and disciplinary boundaries. Judith Butler is a great philosopher, but their work is consistently relegated to ‘feminist theory’ or ‘queer theory’. Likewise, the problem of exclusion is compounded here. Women’s representation in philosophy is poor, but the representation of non-white philosophers, is really awful. In an interview in The New York Times in 2018, Professor Anita L. Allen said:

“White women are better represented and perhaps more easily accepted in philosophy than men or women of color… Only about 1 percent of full-time philosophy professors are black, whereas about 17 percent are women. [And] A higher percentage of black men than black women PhD students go on to tenure-track positions.”

This is undeniable. Those women who are taken seriously as philosophers are most often straight white rich women. The question of racial exclusion in philosophy is something that needs to be taken far more seriously.

Is there a great deal of unconscious bias in philosophical circles?

For some of the talks that we’ve given in schools, Lisa my co-editor and I have tried to look into why philosophy has such a terrible ‘women problem’. We’ve read surveys, for instance. In one study that really struck us, people in different disciplines were asked how much they thought ‘innate genius’ was important to their subject. Philosophers rated it incredibly highly (‘Expectations of Brilliance Underlie Gender Distributions across Academic Disciplines’, Science 347, no. 6219, Sarah-Jane Leslie et al, January 16, 2015). Yet of course, who exactly is perceived as having this innate genius is something that will be gendered and racialised.

We have also heard of many people who explicitly still believe that women make bad philosophers. One man that I spoke to while researching a piece on sexual harassment in philosophy said that he thinks women are ‘too hormonal’ to be rational thinkers. This is the kind of thing that we’re up against.

I’ve seen the issue described as ‘overplayed’ – which implies that actually, women are represented fairly in philosophy, and more widely, in academia. What do you say to that?

Things are certainly getting better for women in philosophy, and academia more generally. Yet progress has been incredibly slow over the last twenty years. Philosophy remains the worst discipline in the humanities for female representation. I would really love to not have to spend my time thinking about how and why women are excluded from philosophy – I have other things I’d like to get on with! The idea that anyone would ‘overplay’ this issue is misguided, at best.

Are universities dealing with the issues satisfactorily, and how can university departments become more inclusive?

Universities are beginning to deal with this issue. Even since Lisa and I began to think and write about this, there has been some positive movement. Most of this, though, comes from pressure from students and early career staff. It would be excellent to see philosophy departments hiring more women and other marginalised groups, and supporting them to be able to succeed as well as their more privileged straight white male counterparts. This might include mentoring programmes, or even more basic support, like childcare provision.

Why did you write The Philosopher Queens?

Lisa and I decided to co-edit The Philosopher Queens as a way to push against the dominant perception of philosophy we still see today. The book aims to tell the stories of many women philosophers, showing how their lives affected their work and thought. Importantly, the book doesn’t fix any of these problems. But it is one tiny step. Some young women and girls have told us that, after reading our book, they’re going to study philosophy. This is enough of a reason to have written it.

This is a bit of a basic question to finish on, but I’m curious: Who is your favourite philosopher, and why?

I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint you. I think idol worship is a problem in philosophy, with people often spending their entire lives studying and defending their favourite philosopher. So, I try not to have one. If pushed, Iris Marion Young is my favourite at the moment. She was a social and political theorist who took the world around her incredibly seriously. She died far too soon, in 2006, at the age of 57. I return to her work often.

• Reece Stafferton is a freelance journalist and community organiser with an interest in philosophy. His work can be found at www.reecestafferton.com.