Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Back to the Sophists

Nana Ariel corrects the record and the modern application of Sophistry.

The ancient Greek Sophists are looming in the twenty-first century, especially, it seems, in relation to Donald Trump. Patrick Lee Miller, an American philosopher who knows a thing or two about the ancient Greeks, was reminded of Plato’s critique of his Sophist contemporaries, remarking that “Such disregard for truth, such deference to popular views, such peddling of bulls**t, characterized Trump’s long campaign for the presidency.” Writer Mackenzie Karbon also declared “the rise of modern sophism in the Trump era.” Law professor Frank O. Bowman III called Trump’s impeachment defense “a well-crafted piece of sophistry that cherry-picks sources and ignores inconvenient history and precedent.” Drawing analogies between the Sophists and the culture of fake news and ‘alternative facts’ has become common too.

It is not hard to understand this tempting analogy. After all, in fifth century BC Greece, the Sophists – philosopher-teachers who wandered through Greek cities teaching students how to win arguments supposedly by any means necessary – were for many a sign of cultural and moral decadence. Their identity as teachers of effective rhetoric and as relativists, resonates with the modern emerging contempt for truth. Calling their opponents ‘Sophists’ helped people process the shock of the 2016 US elections, by reframing it historically, creating the impression that it was not a new era but rather, history repeating itself. It enabled journalists, intellectuals, and various public figures who made this analogy to position themselves on the right side of history – that of truth and justice, represented in ancient Greece by Plato, who condemned the Sophists, denouncing them as dangerous charlatans.

An uncritical embrace of Plato’s stance towards the Sophists, has been the established narrative throughout Western history. The reproaching voice of Socrates in Plato’s dialogues has made ‘sophist’ a common pejorative for populist politicians, unscrupulous lawyers and ignorant mentors up to this very day. But now the shock of the ‘post-truth’ storm has died down to a weary rumble, the original Sophists not only deserve to be recontextualized historically, but also can offer us some useful techniques to deal with a culture of excessive information and conflicting truths. In other words, sophism is not necessarily the problem; it can be part of a solution.

Returning to the Sophists by moving beyond Plato’s critique of them is not new. In the last two hundred years many thinkers have reclaimed them as worthy ancestors. Some key moments in this late reception seem to me particularly interesting for today’s discussions about populism, knowledge, and competing truths. But first, a few words about the moment in which the original Sophists emerged.

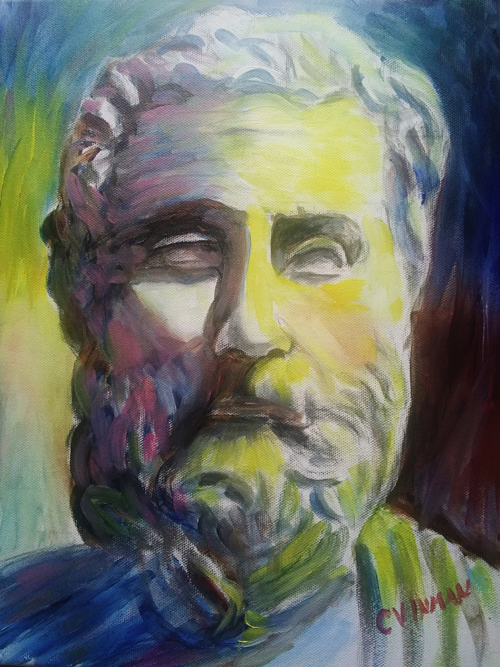

Protagoras by Clint Inman

Painting © Clinton Inman 2023 Facebook at Clinton.inman

The Original Sophists

The philosophers who wandered through Greek cities to teach students were not a homogeneous group. They were independent tutors, mostly non-Athenians, who not only taught skills of rhetoric and politics, but were also pioneering researchers in linguistics, poetry, and science. The emerging democracy of fifth century BC Athens increased the need for education to prepare people to participate in the affairs of the polis (Greek city state). Whilst previously a young man would receive the mentorship of a more experienced man of a similar status, the Sophists, who were often gifted intellectuals, sought to break this dynastic, aristocratic structure, and liberalize education. The Sophists, not to be confused with ‘demagogues’ who were populist leaders, can therefore be seen as the first professional teachers and the first promoters of higher education.

The fact that Sophists received payment for their teaching will probably not shock modern students still paying off their loans. However, in ancient Greece, payment for teaching philosophy was associated with corruption. And some of the Sophists, such as Gorgias or Antiphon, became quite rich from their teaching, which increased the stain of egoism, deception, and betrayal of moral standards attached to them.

The foreignness of the Sophists and their frequent migration between cities were also causes for suspicion. Protagoras of Abdera, Gorgias of Leontini, Hippias of Elis, and others, were not seen as an organic part of the Athenian polis. Not only were they not political leaders, some of them were not even citizens – and they impudently dared to teach the Athenians to speak, discuss, and debate!

The Sophists were charged by Athenian aristocrats and conservatives with the typical allegations against foreigners and newcomers: the undermining of values, and corruption of the youth. But it was precisely their foreignness that played a significant role in their philosophy. Their movement between cities allowed them to act and see independently, and to clearly identify the differences in social norms and values between the disparate places they wandered through. Thus they began to develop the idea that values are not eternal verities but social constructs. The first Sophist, Protagoras, claimed that “Man is the measure of all things” – essentially meaning that subjective human judgment constitutes reality, and so values are not dictated by an external moral entity such as the gods (Protagoras also became the first agnostic on record, by claiming that he didn’t know whether they existed). So to Protagoras morals are not external to human experience. Rather, it is people who determine what is true and right. Protagoras did not claim that there is no truth; only that we can reach what we perceive as true only through our ad hoc perceptions.

Generally speaking, the Sophists realized that norms, conventions, and laws are what enable people to act together and reach agreement in situations where the truth is elusive. This philosophical stance has direct political consequences: it leads to the radical idea that all citizens (well, initially, all property-owning males) are politically competent, and potential judges in the arena of democratic politics.

Protagoras, though, did not perceive this competence as a given – it is, rather, a potential that can and should be nurtured through education. The idea that education would open up the possibility of political leadership to the masses and lead to class mobility, is seen (even in this day) as a threat to elites. It is no wonder, then, that the Sophists who promoted it were deemed dangerous: they were seen as purveyors of democracy out of control.

The teaching methods of the Sophists were varied: they taught in small group seminars, wrote treatises, and performed sample speeches to show their students the different techniques of rhetoric and argumentation. Most of their writings and speeches are unfortunately lost, but the few remaining are illuminating, such as the Encomium of Helen by Gorgias – a Sophist renowned for his impressive, rich language, and his tendency to use language games and sophisticated paradoxes.

In the Encomium, Gorgias turns to the mythology of the Trojan War, and defends Helen, who married Menelaus, king of Sparta but eloped with Paris, prince of Troy. Her departure led to the war, and Helen was deemed a treacherous woman, responsible for the ensuing destruction. Gorgias provides four possibilities that might explain her deed: she was either led away by the will of the gods, or by force, by the power of words, or by the temptation of love (Eros). Each option shows that she was a victim to be pitied rather than blamed.

The closing line of Gorgias’s discourse has puzzled generations of readers: “I wished to write a speech which would be a praise of Helen and a diversion to myself.” This breaks the severe tone of the speech and hints that its subject is not really the poor, defamed Helen, but the art of rhetoric itself. It is indeed an exemplary speech for students, which showcases the power of argumentation, and is amusing indeed, especially as there are no real consequences to defending a mythological figure. Yet this unthreatening and playful tone enables Gorgias to present the radical critical process of subverting accepted stories and common beliefs through an array of possible narratives and counter-arguments.

The Sophists did not necessarily teach how to “make the weaker argument stronger,” as they were accused of doing in popular texts such as Aristophanes’ comedy The Clouds and Plato’s and Aristotle’s writings. Rather, they emphasized that competing arguments are the lifeblood of democracy. The anonymous Sophist treatise Dissoi Logoi, or ‘Opposing Arguments’, presents a series of paired claims that can each be valid in different contexts. For example, For example, it states that in case of war the victory of the Spartans is good for the Spartans and bad for the Athenians, and the victory of Athenians is good for the Athenians but bad for the barbarians. Thus, blind righteousness with regard to war is rejected in favor of a skeptical stance that acknowledges another point of view. This is not nihilistic moral relativism, according to which all arguments are valid (and therefore none of them are), but rather, recognition of the fact that arguments are often a matter of perspective. They can be seen as valid or invalid, weak or strong, only within specific contexts. Practicing presenting opposing arguments is therefore not a way to deceive or manipulate, but rather a way to nurture the skill of listening to opposing voices and acknowledging others as legitimate arguers. The presentation of opposing arguments was not the end of Sophistic discussion but rather its beginning. The Sophists’ students then debated, discussed, and challenged each other with questions. In fact, it was the Sophists who invented the so-called ‘Socratic’ form of dialogue, in which philosophical truth is discussed and negotiated. But while Socrates often strove to expose the ignorance of his interlocutors in order to reach what he claimed was true, in order to reach an agreement about what may be considered reasonable and acceptable, the Sophists treated both sides as equally competent.

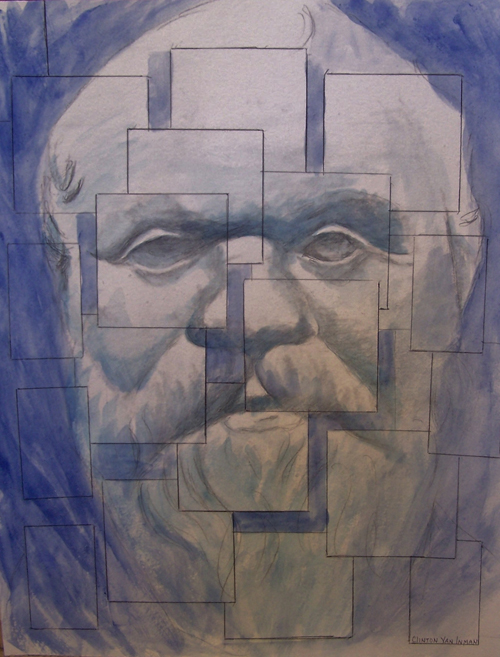

Socrates by Clint Inman

Painting © Clinton Inman 2023 Facebook at Clinton.inman

The Sophist Legacy

Presenting subversive readings of popular stories, creating opposing arguments, practicing alternating perspectives, engaging in dialogues between equals – the Sophists offered an array of critical tools that enabled the realization of articulate citizenship in the polis assembly, in courts, and in everyday lives. Nevertheless, Plato’s representation of the Sophists in his dialogues is harsh. Through Socrates, he presents them as self-declared experts who pretend to hold knowledge about truth and justice while in fact having no specific area of expertise except the ability to persuade people to hold precarious opinions by using verbal manipulation. He presents them as dubious experts at argumentation as opposed to real seekers after the truth – the real ‘lovers of wisdom’, the philosophers. In his dialogue Gorgias, he compares the Sophists’ teaching to cooking and cosmetics that offer superficial joys that attract the masses, as opposed to gymnastics and medicine, which actually improve the body. This image of the Sophists not only serves Plato’s anti-democratic philosophy and claim to be an arbiter of the truth; it is also an attempt to clear the name of his teacher, Socrates, who was sentenced to death for allegedly being a Sophist.

Plato’s fatal criticism of the Sophists has persisted throughout Western history, and has paradoxically marked them both as an everlasting, ever-lurking danger, and as weak, minor figures who only play a minor role in Plato’s theater. This reputation started to change only at the beginning of the nineteenth century, partly as a result of the philosophy of GWF Hegel, and even more so down to the English historian George Grote, who dedicated a praising chapter to the Sophists in his History of Greece (1846), attempting to correct Plato’s misrepresentation of them.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) also presented a new portrait of the Sophists, which resonated with his own philosophy. For him, they were the first to realize that language does not simply reflect truths, but instead maintains a constant negotiation with meaning and interpretation. Compared to Plato’s pretension to grasp universal truth and justice, the Sophists are aware that truths and morals are determined within a framework of discourse. Interestingly, Nietzsche’s Sophists are not merely historical figures in ancient Greece, but the carriers of philosophical energy throughout history. In The Will to Power he wrote that “Every advance in epistemology and moral knowledge has reinstated the Sophists.”

Twentieth century thinkers responded to this call. While historians continued to challenge the accepted historical denigration of the Sophists, some philosophers were intrigued by their ideas. From Martin Heidegger through Richard Rorty to Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, and Jacques Derrida (to name but a few), philosophers penetrated Plato’s monolithic account to reach the voice of the Sophists, resonating with postmodern ideas about the relativity of truths.

Perhaps the most surprising turn in the Sophists’ reception was their revival in feminist writings since the 1980s. This may seem puzzling as there is no hint of a progressive position towards women in the Sophists’ accounts we have. Like their contemporaries, they did not even perceive women worthy to be voting citizens in the polis. However, post-1980 feminist attempts to challenge patriarchal concepts of truth and logic included a search for alternative models – one of them being that of the Sophists’. For feminist thinkers and rhetoric teachers such as Sharon Crowley, Susan Jarratt, and Michelle Ballif, Sophistic ideas here correspond with feminist ones, and provide an opportunity to rearrange knowledge on rhetoric, writing, and education. They were inspired by the Sophists as teachers, and by their creative, playful, and critical teaching methods. Their embrace of the Sophists is often deliberately anachronistic – it is a self-conscious attempt to expropriate the Sophists from their historical context and present them in a new light in service to present political goals. In Susan Jarrett's book Rereading the Sophists (1991), for example, while emphasizing that the Sophists were not ‘feminists’, she reads Gorgias’s Encomium of Helen as a text that subverts the “violent logic and ethos of a phallocentric culture.”

Modern Sophistry

Some modern thinkers, therefore, have resisted Plato’s condemnation of the Sophists and presented them as inspiring radicals. Many of them indeed recruited the Sophists for their own theoretical interests and recreated them in their own image; but even by doing this they have shown that the Sophists’ bad reputation is not a given, and that they can return under a new guise to tell us something about the present. These two questions remain, though: What can the Sophists offer twenty-first century public discourse and education? And are the Sophists indeed the ancient emblem of post-truth?

While the Sophists never claimed to own the truth, contemporary populist politicians such as Trump seem to be obsessed with truth, even naming his social media platform ‘Truth Social’.

Trump resisted the teleprompter polished rhetoric of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, recasting it as a sign of falsification and concealment. Throughout his election campaigns he rejected the teleprompter in an attempt to create the impression that he is a truth-teller who repudiates rhetoric. In fact, this assumption that improvised talk is a sign of truth echoes the anti-Sophist voice of Socrates in Plato’s Apology : “from me you shall hear the whole truth: not, however, delivered after their manner in a set oration duly ornamented with words and phrases. No, by heaven! but I shall use the words and arguments which occur to me at the moment; for I am confident in the justice [of my words].” It is exactly this confidence in his exclusive access to the truth that was the central feature of Trump’s rhetoric. To him, he is the only measure of all things.

The phrase ‘alternative facts’, first identified with the Trump administration, may misleadingly sound like the Sophistic method that allows two opposing claims to be presented for every purpose. The phrase has had currency since presidential adviser Kellyanne Conway used it to justify false data provided by White House press secretary Sean Spicer about the number of attendees at Trump’s inauguration. The idea was criticized because it was seen as a ridiculous and dangerous challenge to truth – numerical facts are incontrovertible, and if they can be verified there can be no alternatives. However, Conway’s statement did not imply the possibility of holding two claims at the same time, checking and confronting them, but that one of the claims – the contrived data in her hands – was the (actual) truth. This discourse of alternative facts and fake news is therefore the opposite of the Sophistic practice of opposing arguments. While the Sophists wished to raise awareness of the necessary existence of competing claims in a democracy, Trump offered a monolithic position where there is room for only one truth – his own. Tom Ribitzky thus rightfully argues that “Sophistry should not be confused with lying. It has nothing to do with ‘alternative facts’. Trump and his ilk are not Sophists” (T. Ribitzky, ‘Teaching Sophistry in the Age of Trump’, Visible Pedagogy 22.03.2017).

Bryan A. Lutz declared that the Trump era created ‘Digital Sophistry’, and suggests that critical teachers and students should ‘play’ Sophists for the purpose of developing a critical stance that rejects them. However, why pretend to be Sophists if we can just… be Sophists? Thinking of their original tracts, the real Sophists, as opposed to demagogues, were far from promoting a culture of deception and manipulation. In fact, they promoted techniques that can help us deal with conflicting truths in the information age, in which more people than ever are making their voices heard in the public sphere. These methods are not meant to replace fact-checking or science; they are intended to help us examine the reasonableness of arguments in their contexts. They deal in particular with situations in which clear-cut truths are unreachable – exactly those moments where fact-checking and formal logic can’t help us determine whether we are being treated fairly, or misled and deceived. As Gorgias said, people cannot remember all the past, know all the present, and predict all the future, so their ability to reach absolute conclusions is limited. This is possibly even more the case today, when an overwhelming amount of data surrounds us. And while the internet and AI can potentially help us remember the past, know the present, and predict the future better than ever, for the time being they cannot replace subjective human judgment and decision-making in complex situations.

Think of the method of Dissoi Logoi – raising opposing arguments, which enables us to examine issues from multiple perspectives and understand the mindsets of others. Isn’t this absolutely necessary for breaking through our echo chambers, in which people are only exposed to similar voices and opinions, prisoners of their own limited perspectives? Isn’t it the exact opposite of any monolithic social network arrogantly called ‘Truth’? Or think of Gorgias’s Encomium of Helen. He takes a shared narrative everyone knows, and systematically dismantles it until it becomes a dance of alternating perspectives – a modern equivalent would be the film Rashomon [reviewed in Issue 127, Ed]. Think, in turn, about some of the mythologies in our own culture, in our own close communities – the stories that we tell repeatedly without questioning them; stories on which we base our shared values and beliefs. Wouldn’t it be useful to question the truthiness of these beliefs by imagining alternative readings of these stories? Can’t Gorgias’s method serve as a playful and nonviolent critical tool for dealing with stubborn tenets?

The ‘new Sophists’ can be defined in a better, more accurate way than that label is usually presented now in public discourse – not as a name for populist charlatans, but as a positive badge for critical commentators and thinkers, as ‘wisdom experts’ who deal with excessive information and competing truths by activating Sophist practices. In fact, contrary to their reputation as villains, the Sophists’ humanism helps us remember that being the measure of all things comes with great responsibility, and that wisdom experts can also be wisdom lovers.

© Nana Ariel 2023

Nana Ariel is a rhetoric scholar from Tel Aviv University, previously a Fulbright scholar and a guest lecturer at Harvard University. She has published in Aeon and Psyche magazines, among others.